Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Desne A. Crossley: Alzheimer’s and Missing Love (2015-2017, 1996 & 1950)

Hola Michael,

I hope all is well with you. Happy Valentine’s Day. It’s amazing how time just blasts by.

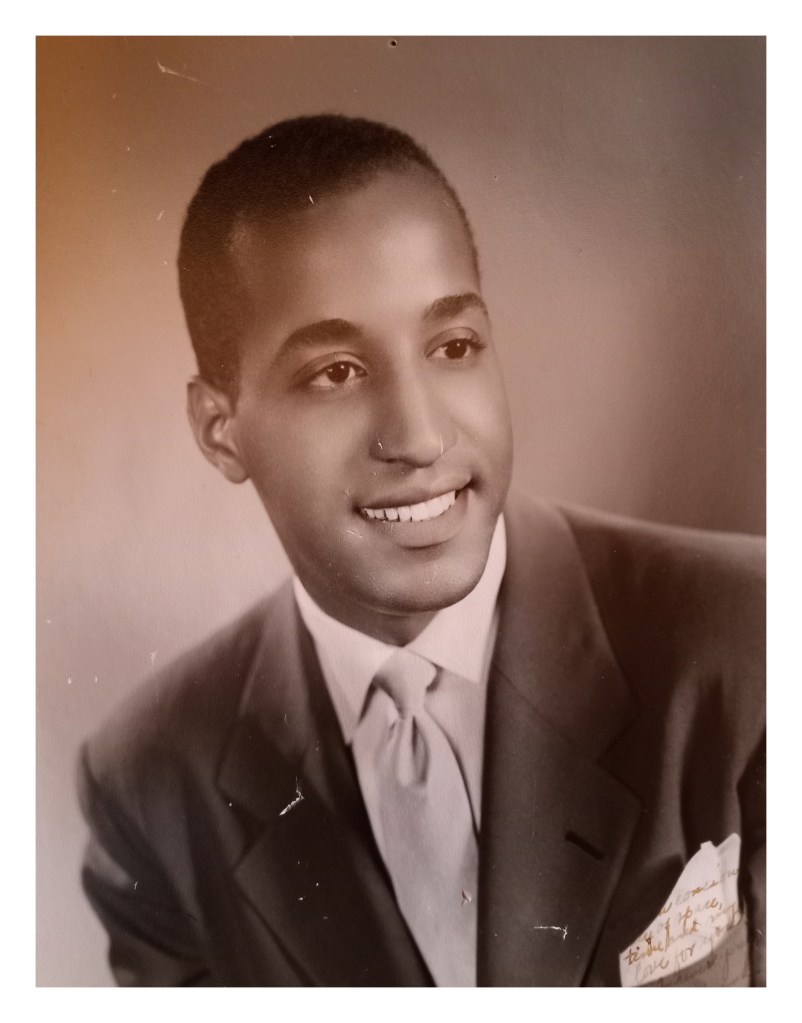

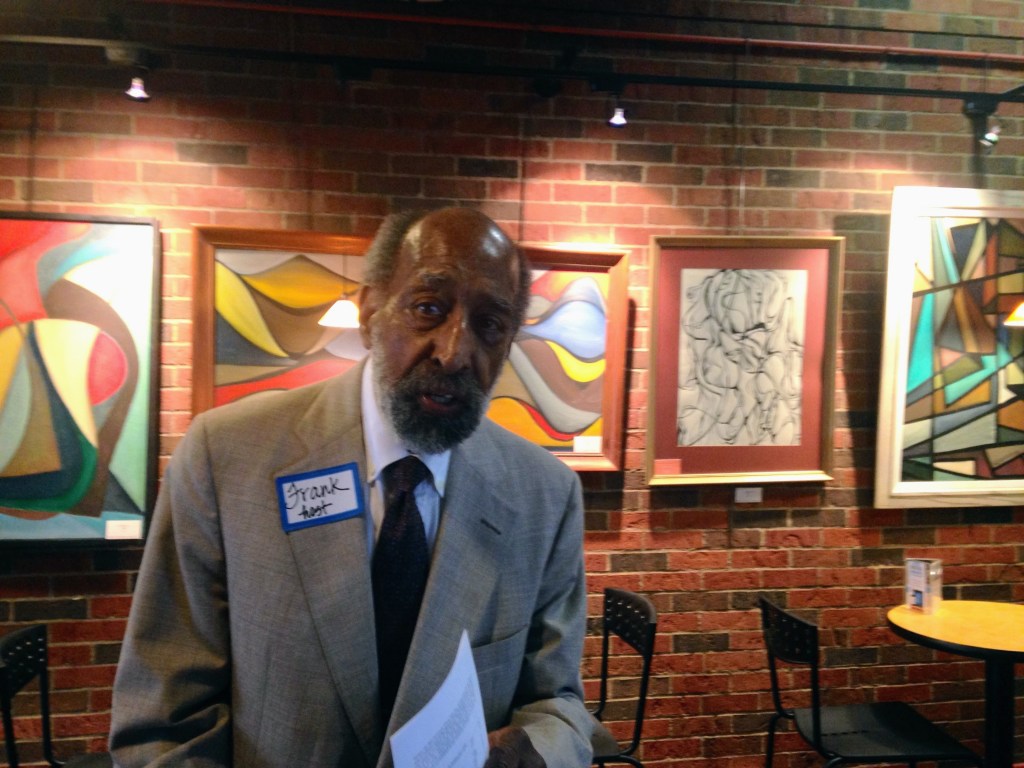

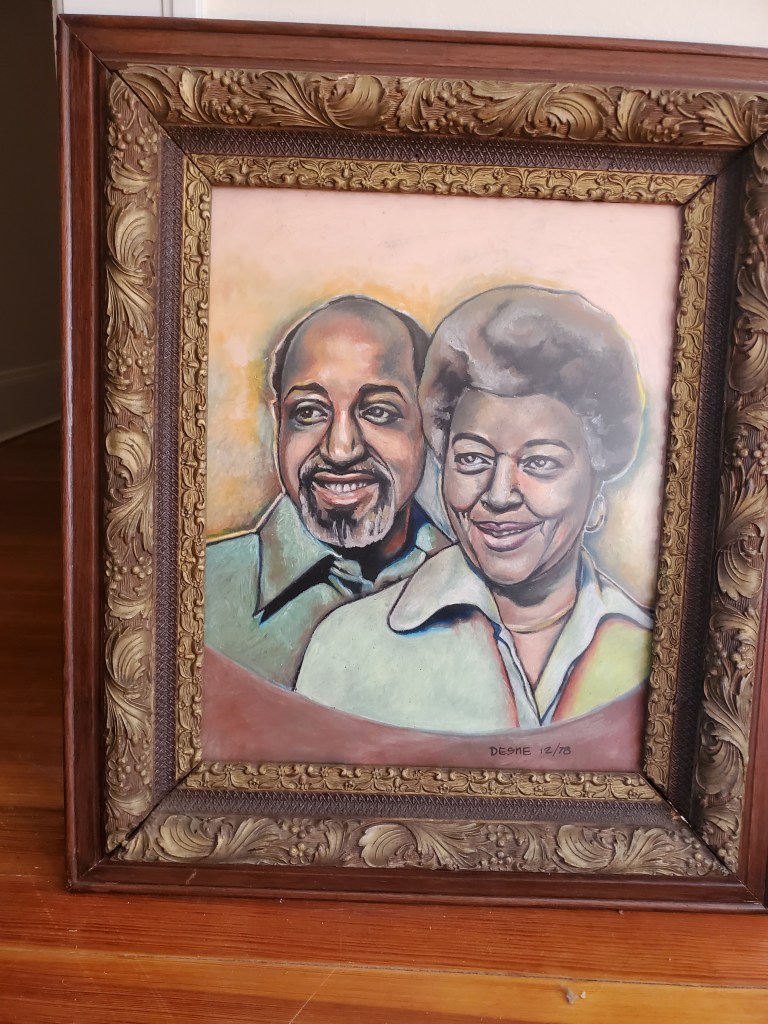

I’m thinking about my folks a lot. Watched the movie Hidden Figures (when the first black women worked in the Nasa space program) and almost cried. My father was a rocket scientist, something I didn’t realize until his brain was already gone to Alzheimer’s. He just called himself “Mr.” Crossley and a “metallurgical engineer.” He only used “Dr.” at work. My parents were opposites in a lot of ways, but best friends. About a month before she died in 1996, Mom said “Your father would stand on his head in shit if he thought it would make me feel better!” (At last, she realized she had the love she’d longed for.)

At ninety, a bad fall and concussion changed everything. My father had been a youthful eighty-six. A year later he had aged ten years but still lived independently (a term I’m using gingerly) in Framingham. It was the family’s good fortune that he and the Meals on Wheels lady had developed a friendly routine. This morning, she spotted him and a big blood stain at the base of the staircase through the pocket windows along either side of his front door. The lady ran over to Dad’s next door neighbor Nandy Paloma for help. I had given the Palomas a key sometime earlier, just in case. According to Nandy, he was still in his bathrobe and resembled a washed-up fighter, one eye swollen tightly shut; he was stumbling and dazed when she saw him. She called Ken at home in Attleboro, me at work in Cambridge, and a local ambulance.

At the hospital, the emergency doctor refused to release my father without a plan. It was unsafe for him to live alone another day. Was there somewhere he could go?

“Yes, I’ve got Ken and his wife,” my father replied, gesturing to his son-in-law—with me standing right beside Ken.

Unceremoniously, Dad moved to Ken’s and my home on September 15, 2015. He would awaken the next morning wondering why he was at our house. Days later, he would say he thought he lost consciousness at the second-floor landing and that his face must have hit the oak newel post on the way down.

As much as I was a daddy’s girl, the new living arrangement would overwhelm my husband and me emotionally and logistically. We gave Dad two rooms and a bath. For nine months, Ken was Dad’s primary care giver during the day, until I returned home from Harvard Law School around 8pm. Ken and Dad had much in common but did not get along. The expression, Dad “jumped on his last nerve,” summed-up their relationship. As soon as I turned the key in the door lock, Ken was off duty, and I was on. I would prepare Dad’s fourth and last hot meal of the day—a ritual Dad insisted upon—, pick up stray diapers discarded wherever he had stepped out of them, catch up with him for about forty-five minutes, try to be jovial enough to make him smile and laugh, ready him for bed, and on occasion watch a little television before I kissed him on the forehead goodnight.

His legs were growing weaker, his balance increasingly inconsistent. Always stubborn, Dad’s advancing Alzheimer’s amplified this trait to outright obstinance. Once, he and Ken got into a physical tug-of-war over an aluminum mixing bowl containing coffee that Dad was about to warm in the microwave. (Meanwhile, a nearby ceramic mug of coffee went unnoticed on the counter.) My father tried to wrest the bowl away from Ken, insistent on having his way. His once dependable logic was nowhere to be found. Their voices grew loud. Coffee spilled around them—one more thing for Ken to clean up.

That year, my world was a tsunami, with me struggling to fight incompetence and keep my head above water. Work, travel for work. Emptying and repairing my father’s neglected five-bedroom house, cluttered with memories of my mother and papers he no longer knew what to do anything about. Prepping his house for sale. Figuring out his taxes. These were all my jobs now. I had been in denial earlier and believed him when he complained, often, that arguing with the IRS for almost five years had burned him out. Yes, he insisted on preparing his own taxes, sure that experts did not understand the old-style family trust my parents set up in 1984. He reasoned that out of a thousand pages of instructions, policy, and tax law, only one of those pages dealt with family trusts and there was no mention of the kind they had. He also held fast that, so long as he could make sense of those thousand pages, his brain was healthy. At the same time, his accountant instructed him to just pay back what the IRS said he owed. My father endured; certain he was right. It was a point of pride that the IRS conceded, finally each year, that his taxes had been prepared correctly, and they had been wrong. I was outraged that they repeated this audit of an old middle-income man every year until I took over his taxes with H & R Block.

Geography was just another hurdle. Attleboro was forty miles southwest of my workplace, and Dad’s house was thirty-four miles northwest of our house—an inconvenient triangle of three or four highways. I had no time to be anyone’s friend, but my friends graciously understood and kept the love coming. Coworkers were quick to remind me to “put your oxygen mask on first.” I knew in theory they were right but had no idea how actually to do it. Ken and I hustled from chore to chore, focused on keeping pace.

In March 2016, Dad’s two-story contemporary colonial listed for sale at ten percent below market—my decision. I did not have time nor the energy to haggle with potential buyers. Moving between Cambridge, Framingham, and Attleboro in dense, creeping traffic could make me feel crazy. Dad’s house received three offers in two days. It sold to a young family exactly right for the place—at asking price. In late May, we closed the deal. Ken and I could not have gone on much longer without a break.

We found a facility in Mansfield (near a highway between work and home) that provided “respite care” for overwhelmed care givers. Ken and I signed Dad up for a week. This was part of our larger strategy to place him there permanently if he liked the residence. The director of community relations arranged a tour of the Village at Willows Crossing’s memory care unit. One of the residents had been an artist, and her paintings were handsomely hung on every wall of her room. It looked just like someone’s private dwelling. Dad sat in a side chair in the room, marveling at the occupant’s space. The staff arranged for us to have lunch there, the kind of meal they served regularly. Dad liked the food, too.

The director of community relations was a dark-haired beauty with long, sleek legs and a winning smile. Dad’s eyes sparkled when she spoke to him. She asked how he met his wife, whom she knew had died almost twenty years before.

Dad pushed back in his chair at the big table and pressed his fingertips together thoughtfully. I knew he was settling in for a long tale, delighted for the opportunity to reminisce.

“I met Elaine at the Illinois Institute of Technology when I was a student. She was a nude model for my art class,” Dad began.

What? I could not believe it. First, it was not true. Second, I doubted that Illinois Tech’s curricula, circa 1942-1950, included art classes with naked models. I exhaled. At least his telling of this tale affirmed our decision to find a facility for a heightened level of care.

The director said, “I’ll bet she was beautiful.”

Dad looked upward, as though his memories were painted on the ceiling. “You bet. She was a real beauty.”

The director looked my way. I could tell she believed him. So very slightly, I shook my head and lowered my gaze. She got it.

In six months, my father no longer talked much and sometimes his tongue seemed uncharacteristically thick or uncooperative. Maybe he needed encouragement to keep the speech flowing, so I asked him over Thanksgiving dinner 2017 at the Village to tell the story of meeting my mother. He smiled. His words came haltingly.

“It was World War II, and I was in the service. Your mother was a volunteer, entertaining the troops, when I saw her. I was in the audience.”

Dad did not know what to do with the story next and paused to check the ceiling.

“I got a chance to meet her off-stage… and we dated for six months… we got married in her hometown, and we were apart then together in the War.”

At times, he lost sequence. It mattered to me only that this telling of their meeting, as well as subsequent variations, were pure fantasy. Would there come a time when nomemory of my mother, his “Golden Baby,” remained at all?

Dad’s brain continued to degrade. After emergency surgery for a hernia, many forgotten falls, pneumonia, hospitalizations, and stints at rehab facilities to regain strength, his memories faltered even more. An aide at the Village asked how he met my mother.

“I think her mother introduced us.” Dad was unsure. “Her mother was involved… somehow… I think…”

Another time, another aide was holding him steady as they entered his room and asked if his wife had painted the abstract oil of sensuous hills. He had slept under it since 1997. At first, he did not know and stared. “Yes, I think she may have done it.”

I loved the story of how they actually met, with Mom and Dad telling it together.

The last time they told it, in 1996, Mom began, “It was the Fourth of July of 1950, and I was on a date with a guy, a friend of one of my brothers. It was a picnic in Dayton, Ohio.”

Dayton is roughly fifty miles north of Cincinnati. I was thinking it was a long way to travel with a not-so-special guy.

“I had been playing baseball and got tired. I went off by myself to sit on a bench away from the game and your father comes up to me. He asks, ‘Are you lost?’ like I’m some kid. I say, ‘No, I’m tired… I’ve been playing baseball over there.’ I point toward my friends who are still playing.

“The next thing he asks me is—can you believe this—, ‘What grade are you in?’ Shit, I was twenty-five-years old, so I say, ‘What do you mean, what grade am I in?’

“Your father says, ‘You’re not in high school? You look like you’re sixteen.’

“I say, ‘I’m a twenty-five-year-old woman.’ Your father says, ‘Really? I’m twenty-five, too.’

“I’m looking at him closely, this crazy man, thinking he’s got the kindest eyes I’ve ever seen. He thought I was sixteen. I thought he was thirty-three,” Mom laughed. “He asks me out on a date for Monday, and I tell him I don’t know if I can go because I don’t know if I’m still married or not. I tried to get a divorce, but anybody who could’ve helped me was a fraternity brother of my husband. They just got a big laugh out of it.”

My father had just finished his PhD at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago and was on vacation in Dayton with people he knew.

“On Monday, your father tells me I can go out with him because he’s checked the records at City Hall and Roy Stroud, my ex, has divorced me. That’s the way it was back then… women didn’t have any power. Can you believe that? I hadn’t been notified that I’m divorced….

“Well… Frank goes to get me a corsage to wear for our date…”

My father jumps into the story. “Of course, I ask around and go to the black florist, the only black florist in town. Sherman’s Flower Shop. I’m in the Shop and trying to explain the kind of corsage I want.” Dad uses his cupped hands to indicate the size for Mom’s thin shoulder. ‘Red sweetheart roses, not too big because my date is tiny.’ I can tell that the owner is getting mad. He thinks I’m telling him his business and assures me he knows how to make a proper corsage. I don’t know it yet, but I’m dealing with your grandparents.” Dad chuckles and shakes his head. “Your grandmother is on a tall stool beside him. They’re sizing me up. They ask where I’m from. ‘I’m from Chicago.’ They ask what I do for a living. ‘I’m a brick mason,’ I say because I don’t want to have to say I’m an engineer. Maybe they’d just think I was bragging or telling lies. They’re smiling at me now because a brick mason is a respectable job for a black man.

“We continued talking and they seemed so nice that I asked if they knew where Fredonia Avenue was. The owner says, ‘Yes, I know where it is.’ They’re giving directions and I’m getting ready to map it on paper. He says, ‘We live on Fredonia. What number are you going to?’ Husband and wife are leaning forward, studying me. I give the number, and he says, ‘That’s my house. Which one of my young-lady-daughters are you supposed to see tonight?’ I say, ‘Elaine.’ They study me some more. ‘You’re Elaine’s parents?’ Here, I’m finally getting what should have occurred to me earlier, maybe, but your mother introduced herself as Elaine Stroud, her married name.

“Well, when I get to the Sherman house, Des, your mother is sweeping the sidewalk out front. I’d never seen anybody do this in Chicago, so I ask why she’s bothering to clean a city street. She looks at me funny, then says, ‘Because it’s in front of our house.’ I offer to finish up, and your mother hands me the broom. She walks toward the house, then turns back. ‘Would you mind sweeping the third-floor steps to the attic, too? I’m behind in my chores today.’”

My father continues, “Sure. I won’t be long finishing up. Why don’t you go on and get dressed?”

Mom jumps in again, smiling. “No date had ever offered to help me with chores. We went out and talked and talked….”

My father was smiling too. “I asked my ‘Golden Baby’ to marry me on our third date.”

“—No, Frank,” Mom interrupted. “You asked me on our first date. I thought you were crazy. I didn’t say ‘yes’ until the third date.”

I half-laughed, “You guys never agree on the details of that story.”

Now that Dad’s Alzheimer’s had snuffed out this cherished memory, I mused about the “how I met your mother” stories: Mom as nude model in an art class, Mom as entertainer of troops during World War II, Dad asking Mom to marry him on the first date. In each, my mother was beautiful, a stand-out, irresistible.

Copyright 2026 Desne A. Crossley

~

~

~

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sadly, I was with Crossley all the way in this powerfully written piece. Too many of us are overwhelmed by caregiving a loved one with Alzheimers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are a hero, Ellen. Bless you!

LikeLike