Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

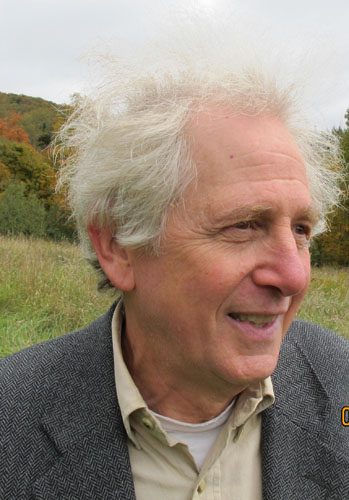

Dawn Potter: Remembering Baron Wormser

“The hand that lets go”

.

In 1983, Baron Wormser published his first collection of poetry, The White Words. Now, more than forty years after it appeared, I open to the book’s second poem, “Of Small Towns.”

The surmises that the metropolis loves

To make, the crushes of people whose names you will

Never know, the expansive gestures made

Among incoherent buildings—all that is

Peculiarly urban and self-aware is lacking.

Instead you have a hodgepodge:

Legends hovering, dreams that lapse into

Manias, characters ransacked like cottages

In winter.

It is this last image that brings me to tears. How, as young as he was then, did this city-bred poet step so surely into the harsh eloquence of rural loneliness?

Baron’s wife, the painter Janet Wormser, spoke to me about the years when he was writing this first book, a time when they were living with their two children in the house they’d built themselves off the grid in rural central Maine. He’d grown up in Baltimore, where, far too early, he’d become his dying mother’s caregiver and was left to manage a fractured, uneasy household. The wounds were deep. In Maine, she said, “he was so happy just to be left alone.”

And yet for many of us who came to know him as a poet, a colleague, a teacher, his great gift was helping us notfeel alone. A friend, the poet Bruce Spang, recalls visiting that house in Mercer: “We would sit by a kerosene lamp, [Baron] on one side reading my poems, me on the other, anticipating a response. [He] would read and give one of [his] long, thoughtful sighs, and I knew, right off, I was in trouble.”

But with Baron, trouble was what we craved. I, like Bruce, underwent these sessions of patience, sympathy, and implacability. With every draft I shared, Baron made it clear that writing poems might be the most excruciating task I would ever undertake in this world. Still, being his apprentice was like being born again. A poet had looked into my mind, had seen what it was, what it was capable of. Baron gave me, and so many others, the gift of our vocation.

In his memoir The Road Washes Out in Spring, published in 2006, Baron wrote: “What brought me to the woods was grief” over his mother’s “protracted, harrowing death.” But also:

What brought me to the woods was the prospect of living with nothing between me and the earth. . . . What brought me to the woods was an impulse to get lost, to be almost literally off the map. . . . What brought me to the woods was generational, . . . the little tide of people who wanted to return to a countryside they had never experienced. . . . What brought me to the woods was pragmatism. I wanted to learn to take care of myself. What brought me to the woods was being an urban Jew who was ready to leave behind the vestiges of assimilated religion and culture that had been bequeathed to me. . . . What brought me to the woods was the longing to be with words in an undistracted place.

These agonies and desires echo throughout Baron’s many books. But as he wryly concluded in Road, “when we look for one thread of motive, we are, in all likelihood, deceiving ourselves.” Throughout his myriad poems, essays, and fictions, he underwent rigorous self-examination, rigorous observation of the world. And then, again and again, he pivoted into unknowingness, an almost Whitmanesque dismissal of any pat moral conclusion. His life’s work was to see life—squarely, and slant.

Despite the grief that bubbled up in all of Baron’s work, the pursuit of beauty was central to his days. The poet Ian Ramsey grew up near Baron and Janet’s homestead:

I remember visiting the house . . . to play with [the Wormser children], how the homestead, surrounded by forest and flowers and woodpiles, felt elegant and simple and clean and healthy. Their home—filled with art and light—felt like something of a refuge from the papermill-and-poverty culture of the Kennebec Valley. I remember playing on that dirt road and in those woods, doing charcoal drawings with Janet, and how Baron was around, often quiet, often insightful.

That atmosphere lingered in all of the places they later lived—a palpable fusion of daily physical work, daily engagement with art, layered with a sort of airy spaciousness, like a Carl Larsson painting.

I met the Wormsers at the end of the 1990s, not long after they had left their off-the-grid home and moved into town. At that time my husband and I, more than half a generation behind them, were still in the woods: in the throes of raising children; struggling with money and jobs and art and firewood and loneliness; enacting a version of the life they had lived before us. Anxious, unformed, uneducated as a poet, overwrought about leaving my children, I’d signed up for a weekend workshop with Baron. Afterward, he’d taken me aside. Looking directly into my eyes he’d said, “You could be a poet. I’ll work with you, if you’d like to do that.” And so began my apprenticeship.

I have never taken a graduate-level class. Instead, Baron became my university, and these regular visits to his kitchen table allowed me to experience a household of focused intent: two artists, for whom creating was a way of being, whether that required putting together words, or mixing colors, or planting tulip bulbs in autumn. From Baron and Janet as partners, from Baron as a mentor, I began to recognize not only the artisan minutiae of a poem but a larger lesson of making. The material for art can reside in daily labor. Thought and deep emotion arise from the work of the body.

Of all of the poetry collections that Baron published, I remain closest to Mulroney and Others (2000), probably because I first read it when I was trying to reconcile the exigencies of poetry with my woods odyssey. Baron’s facilities with language were legion: his ear was exquisite; his dramatic control could feel Shakespearean. But Mulroney was my first introduction to the power of the ambiguous I. What stunned me, as a student poet, was his willingness to enter imaginatively into other lives—not only via straightforward persona poems but in poems that sometimes made it impossible to tell where Baron ended and the imagined character began.

Janet recalls, early in Baron’s career, the moment “when Tom Hart, the editor who kind of discovered his work in Poetry magazine and got his first book published at Houghton Mifflin, first heard [Baron] read at the Blacksmith House in Cambridge. He said, ‘Now I know what a prophet sounds like.’” Musing over what Hart’s comment might imply, I wonder if it was linked to this ability to enter into imaginative fusion with other lives. Again, Whitman comes to mind as a poet able to cross such barriers. Prophets deliver messages that must be heard. They are the consciousness of our kind.

The poem “Portrait of the Artist” exemplifies the imaginative first-person fusion that drew me into Mulroney. The speaker, re-seeing himself as an eight-year-old child, recalls the apartment’s odors of cat and kitchen, the struggle to dress himself, then asks:

This poem may or may not contain a few details from the poet’s life, but it most certainly is not the straightforward personal anecdote of a man who grew up in a Jewish family. Yet it unrolls like the densest sort of memory—haunted, and haunting. The title magnifies this sensation, for it allows the poem to enter into the reader’s own mythology. We, too, are the artist. This is our own dilemma, this burden of misunderstanding and neglect.

.

Why didn’t familiarity make anything easier?

Putting my socks on, combing my hair, deciding

Which of my three pairs of identical shoes I should wear . . .

I held my hands in front of me

Like some sort of faith healer.

I looked at the little mezzotint on the wall of Christ.

He was so sweet and baleful.

He was so little help to me.

Winter was a cap your mother had knit that you

Didn’t want to wear because it was unmanly.

Winter was a grudge.

Winter was the silent type like Brother James

Who never spoke when he thrashed you.

I went to the window and breathed upon it

And traced my initials in the beautiful steam.

My father called. My day was done.

Baron was a central figure in developing and leading poetry programs at the Frost Place. He taught in graduate programs in Maine, Connecticut, and elsewhere. He spent years as a public school librarian. He worked tirelessly with young people and their teachers. Yet though he surrounded himself with people, his essential loneliness was always evident. It was, perhaps, why he was able to respond so exactly to another person’s pain.

The poet Stuart Kestenbaum recalls a moment in 2001, when Baron was teaching at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. It was October; “it had been only a month since my brother was killed on September 11. Baron read his poem ‘Briefly,’ and as he was introducing it, looked across the room at me, where I was standing by the door. The moment, his compassion, stayed with me.”

“Briefly,” also from Mulroney, begins with the physical—“To throw slush into an April stream,” “Or spit into a puddle,” “Or let a stone plummet” “Is to be seized by the plight of vertiginous wonder.”

Plight. With miraculous precision, the word moves us into the heart of loss:

The hand that lets go

Seems godlike

and the pang of that moment

When some minute presence

is borne away for good

Is dizzying

As the dry beech leaf rides

and bobs and darts

Or the snow turns gray

in the water and is gone

And the illusion of anything

being fixed in time

Are tangible

and briefly imaginable.

“Just typing [the poem] now,” Stu told me, “feels like its own memorial service.”

Baron’s influence as a teacher was both broad and deep. On learning of his death, numbers of former students from his days as a rural high school librarian recalled him as the person who first led them into a real relationship with words. Over the course of his teaching career, he brought hundreds of students, of all ages and experiences, into this rare space. Among them was Ian Ramsey, who as an adult rekindled their connection:

He opened me to writers like Miłosz and Ahkmatova, Carruth and A. J. Leibling. . . . I began to really comprehend the mechanics and metaphysics of a poem, . . . learned that it is OK to be heterodox, to go your own way. . . . I learned what it means to be a teacher and mentor, what true commitment means. I learned that poetry is a life, a path, an endless ocean where you never touch bottom. I also had the gift of knowing Baron at the height of his poetic powers, when he had the metaphysical equivalent of a 100 mph fastball, and it opened my eyes to what mastery really means. . . . In my daily life as a teacher and writer, not a day goes by when I don’t consider how Baron’s example is reflected in my actions and being.

Both students and colleagues remember this generosity. The poet Jeanne Marie Beaumont writes:

From 2015 to 2019, I was fortunate to co-teach nine private classes with Baron Wormser in his “Being with Poets” series, weekend-long intensives devoted to the close reading of selected poets and poems. These were intimate groups, limited to a half dozen or so participants so that each one had a voice and room to think aloud within the group. The “being with” aspect spoke not only to the time spent paying close attention to the written work of the poet under consideration, but also to being with each other, as poets, and hearing each other fully, as fellow travelers on the poetic path. In addition, always for me (and I am sure for others), it was a way of being with Baron, for I never taught with Baron without also learning from him how to be a better teacher, a better reader of poems and a better listener. Baron had a knack for creating a sense of keen attentiveness and nearly holy purposefulness to our sessions of reading poetry together, while also maintaining an atmosphere of delight, wonder, and surprise. His sense of managing time was also instructive—when enough had been said about a poem, when we needed a break from the intensity to grab a cup of tea, when to probe, when to quietly sit, or simply, when to break for lunch. The days flowed.

Another colleague, the poet Meg Kearney, recalls his democratic approach to workshopping: “He invited not only [faculty members] but every student around that table to form our ideas, confusions, and suggestions for each poem into questions instead of comments.” As I learned myself from Baron, such small shifts in sentence formation can have remarkable results, not least because they open apprentice poets to the rigors of personal choice rather than keeping them dependent on outside expertise. It was vital to Baron that his students learn to find themselves, and he always made it clear to me that my responsibility as an instructor was to teach myself out of a job. Yet even as he eschewed the role of poet on a pedestal, he was always, always casting his spell. As Jeannie writes, “the connections made in these workshops—developed line by line, discovery by discovery, person by person, voice by voice, and poet to poet—cannot be undone.”

In the last decade or so of his life, Baron shifted much of his focus to prose, producing scores of essays as well as two novels. But the poetry never left him. Before he knew he was ill, he wrote to me about his final collection, James Baldwin Smoking a Cigarette and Other Poems:

Realistically, since I turn 78 this winter, this looks like the last book of poems, though one never knows. In a lot of ways, this book feels like what I’ve been aiming at since the very first book. Not that those books are negligible but for me something sort of came clear when I sat down to organize this book. . . . I like to think I’ve applied some of what I’ve learned from writing novels. . . . And I know you’ve thought a lot about novels and how to get as much life as you can get into a collection of poetry.

As I’ve read and reread this collection, I’ve returned to these words: “What I’ve been aiming at since the very first book.” And of course the heartrending generosity of “I know you’ve thought a lot about novels and how to get as much life as you can get into a collection of poetry.” Always he reached a hand to bring the rest of us into the circle of lamplight.

What did Baron see in this collection that, to him, felt entirely familiar while offering a new sort of clarity? When I spoke to the poet Betsy Sholl about the book, she immediately mentioned its use of the ambiguous I: that same drive to inhabit other lives that had pulled me so fully into Mulroney, published nearly thirty years earlier. In James Baldwin,though, many of those lives belong to women. Betsy said, “I did think of [Randall] Jarrell when I read those poems,” a nod to Jarrell’s habit, in his late work, of adopting the personae of women. But Betsy’s comparison to Jarrell extends beyond point of view. According to the scholar Suzanne Ferguson, Jarrell would “ask always, both explicitly and implicitly, whether the poem tells the truth about the world; whether it helps the reader see a little farther, a little more clearly the dark and light of his situation.” She might just as easily have been speaking of Baron’s work.

The first section of the book is constructed primarily of female voices. Even when the speaker is male or omniscient, the poem’s arc follows the woman’s perceptions. For me, the most touching of these poems are those in which the speaker imagines himself into the mind of his mother. Again, this particular pain is an old story in Baron’s writings: the opening of The Road Washes Out in Spring turns precisely on that grief. But what feel new to me are the glimmers of joyous free will that flicker in this imagined habitation of a mother’s life.

I’ve often thought of Baron as a humane pessimist, a man who loved life yet was skeptical of hope. Many of his essays directly lay out this conundrum, and it persists, in various forms, throughout his poems and fictions. James Baldwin does not backtrack from such complications, but it does linger, with a certain wistfulness, on its characters’ wide-eyed and reckless yearnings—for instance, in “Katherine Hepburn,” the second section of the long poem “My Mother at the Movies”:

“Hollywood,” my mother, who grew up with black

And white, would sigh at the movie’s end, which meant

Rank melodrama, implausible happiness, actresses

Adjusting their stardom to dialogue and dresses

.

(“Katherine Hepburn played Katherine Hepburn”)

And rueful dismissal of glamour, the tinsel-town

Effect that searched out obscure emotional corners

And threw my mother’s longings into a limpid,

.

Remorseless light that led to more sitting

In the socially permitted darkness, everyone quiet—

Anxious bodies at rest—as the basic tale

Unraveled its breathless self, the one of love

.

Overcoming unlove, of a woman clutching

Whatever she could clutch—a man, a child,

A rolling pin, a steering wheel—and looking straight

Ahead at what did not, could not await her.

.

Often the poems seem to work to articulate men’s bumbling cluelessness about the inner lives of women. Baron didn’t exempt himself from such blindness, nor did he rest hubristically on his imaginings. His tone can be tentative, as if awkwardness itself is an after-the-fact, half-lit epiphany. In “Feather,” he stacked questions, arranged images, crossed time, answered nothing.

Did I love the beauty enough?

Did I stop whatever I was doing,

Pause to bow to the trees?

.

On the roadside, a raven hopping,

Avid, fiercely considering

A dead squirrel’s body.

.

Frost on the railing, frost on the stairs.

Poetic tracery, filigree.

Be careful. Slick footing.

.

My wife’s belly, a curve among other curves.

More perfection than I can take in.

What are these hints in what my mother

.

Liked to call “the scheme of things”?

She came home from the beauty parlor

With a new tint, a few well-placed curls.

.

She lived by her lipstick

And had a felt hat graced

With a blue jay feather. “Some bird,”

.

Is what my father would have said.

Before going out, she adjusted how the hat

Sat on her. A signature motion. Just so.

.

And yet the mother enacts herself, as the poem does. “A signature motion. Just so.”

Many of the speakers in the collection purvey this strict, almost ascetic tenderness, but their poems bump up against a crowd of other voices—some orating despair, others a grim comedy; still others pulsing a kind of hysterical aggression. In “Pandemic, March 2020,” “God, in keeping with His deploring persona, / Is not too polite to shout, “‘I told you so!’”

“We aren’t going anywhere in this buggy,”

Chimes in Job. Maybe a wrench will fall

From the sky startling a group of children

Busy playing blind man’s buff. Maybe

The Day of Complete Stillness has arrived.

Maybe the wheels were supposed to come off

But always in the next chapter, not now.

As Betsy Sholl notes, even when such poems edge up to polemic, “music and the surprising turns of mind save them”:

I . . . think of how he was drawn to writers like Dante, Miłosz, Baldwin, and many Eastern European poets—writers who didn’t limit themselves to one narrow lane, but whose curiosity and wonder branched out to many fields of knowledge. Baron was like an old world intellectual and in that capacity very concerned with culture, ethics, or morality. Maybe if he hadn’t had a sharp tongue and a sense of humor, that might have become deadly, but he did have all that wit and irony. . . .

The other thing that really strikes about Baron’s work is his ear. He had a great ear for voices—timing, pacing, diction, etc.—and also for music in general—rhyme, assonance, consonance, sudden lyric eruptions. . . . It is almost as if he had two strong impulses, one to make music and one to make sense.

Again and again in the collection, the poet followed these impulses as he strained to unbox the unwieldy, illogical argument that is, and has always been, America. In that regard, the title poem, “James Baldwin Smoking a Cigarette,” serves as an homage not only to that great writer but to Baron’s own decades-long mission to “examin[e] . . . the messy strictures of truth,” “more history / than one lifetime could swallow.” Still, set against the rest of Baron’s dense body of work, there’s something different about the collection. Perhaps that difference lies in the way in which certain of these poems—“Where,” for instance—simply rest in innocence:

The children ask me,

Where do the songs go?

We look in the air.

We look at the ground.

.

We sing the song

Of the frisky rabbit

Then the song

Of the whistling kettle.

After, in the silence,

We listen to

The air and the ground.

.

Maybe the air and the ground

Hold the songs

And will send them back

In dreams. Like

A kind of thanksgiving.

.

With our voices

We sally forth

Into the barnyard, the prairie,

The stars, the days

That empty out even

As we fill them up.

Wonder persists. Irony and cynicism, morality and evil, even the poet’s own anguish: they cannot stamp it out. There it lingers, green under the fallen leaves.

Early in my apprenticeship, as I was wailing about not being Keats or Dickinson, Baron shook his head in exasperation and told me, “Listen. You’ve got to use your stuff.”

I wish could have talked to him about the stuff of this collection, though in a sense I’ve been talking to him about his stuff for thirty years. The hard work of imagining. The hard work of sound. The hard work of existing. The hard work of humility. In his note to me about the collection, he said, “Something sort of came clear when I sat down to organize this book.” With these poems, we are left to speculate on “something” and “clear.” We are left to linger among his glints and shadows.

After learning of Baron’s death, the poet David Dear, a participant in the Frost Place Conference on Poetry and Teaching, wrote to me: “I happened to be standing near him as the group broke up, noisily saying their goodbyes. He spoke Shakespeare’s ‘Our revels now are ended,’ and looked around but no one seemed to hear. Then he saw me and I smiled to show that I had, and he smiled back. That smile: one of those brief moments of human connection that has stayed with me.”

Baron’s smile . . . weary, wry, lonesome.

How well we knew it. How hard to accept its absence.

As he wrote in one of his final notes to me: “Alas.”

And then, as always, “Love, Baron.”

Copyright 2026 Dawn Potter

Dawn Potter led poetry and teaching programs at the Frost Place for more than a decade and has served as a visiting writer at the Solstice MFA Program, Smith College, Endicott College, and many other institutions. Dawn is the author or editor of ten books of prose and poetry–most recently, the poetry collection Calendar. She was a finalist for the National Poetry Series, and her memoir, Tracing Paradise: Two Years in Harmony with John Milton, won a Maine Literary Award in Nonfiction.

Dawn lives in Portland, Maine, with her husband, the photographer Thomas Birtwistle.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

26 comments on “Dawn Potter: Remembering Baron Wormser”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on January 4, 2026 by Vox Populi in Literary Criticism and Reviews, Most Popular, Opinion Leaders, Personal Essays, Poetry and tagged Baron Wormser, David Dear, Dawn Potter, Friendship, Frost Place, Ian Ramsey, Janet Wormser, Jeanne Marie Beaumont, Meg Kearney, mentor, Stuart Kestenbaum, teachers, teachers and students.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-rNiSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,946,364

A loving tribute. How hard to “accept its [his] absence.”

LikeLike

Yes.

>

LikeLike

I wrote a longer reaction to Baron’s death but had trouble posting it so all i will say is that the poetry world has lost a brilliant teacher and a gentle but passionate voice. This was the first I’ve heard as his passing. Baron was good to me, he helped shape my first manuscript with an insightful critique. RIP Baron and Thank you.

LikeLike

The world has lost a great teacher who lived his subject. Baron was good and kind to me.

LikeLike

Years ago, when I lived in Maine, somewhere in the late eighties or new nineties, I asked Baron for a reference letter as I was seeking a job teaching poetry. I didn’t know him real well, but had been at several workshops he held and he also critiqued my first full manuscript of poetry. All I can say is he was warm and polite and when I suspected he was just being nice to me, he insisted with lots of detail that I look at this or that poem and realize it’s value. I stayed in touch as I was using his reference and he always was faithful in updating his letter. I’ve read his essays here on Vox Populi, and I admired his gentle voice, how it could be fiery an passionate. This is the first I’ve learned of his passing and I know his students will keep his impression and their thanks in their poetic development.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Once more I am in awe and envious of this community of poets, the depth of feeling, the history that I, an old tourist, catch briefly but cannot begin to understand, lacking words and experience. Oh for a poet mentor to point out my foibles or see hope in my awkwardness. Thank you for letting me share whatever I can hold of your insights and shared love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t underrate yourself, Barb. You are one of us.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Dawn for this incredible tribute to a man I scarcely knew, but reading your words, realize what I have missed. What a gift, both his work and yours.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this perceptive and beautiful tribute. Baron and I had the same friendly argument for 40 years, both skeptics, often walking a tightrope over cynicism. Baron maintained that the human species was irredeemably warlike and greedy, and I countered with less essentialist explanations — economic and political systems we might change, even after centuries — that left a door open to hope. You pegged him, for sure: “a humane pessimist, a man who loved life yet was skeptical of hope.”

I loved teaching with him, learning from him, laughing with him.

Thank you again for this remembrance, Dawn. Baron’s work across genres stands with the best American writing of our straddled centuries. As Williams put it,

it is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

I believe “what is found there” in Baron’s work is the beauty, integrity, and sanity we need and will always need.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Richard. I’m glad you recognize the “humane pessimist” vein . . . it felt so particularly and painfully Baron-like, and in some ways makes his generosity as a teacher and a friend seem even more miraculous–that he could believe in us as individuals without trusting as as humankind.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Beautifully said, Richard. Thank you.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful essay, Dawn. Elegiac. And yes…Baron’s questing spirit and his generosity of nature.

I won’t forget seeing him, year after year, emerging from the woods behind Frost’s barn, already bubbling with good will and good words. I miss him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Carlene. I can picture exactly the scene you describe–

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Carlene, for this lovely glimpse of Baron…

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems to me that to write an exhaustive portrait of our late friend Baron’s character– brilliant, wise, puckish, and in the end still somewhat reclusive– would be impossible, but Dawn, you have come as close as anyone could. Thank you! You brought me tears and smiles… just as Baron could do.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Such a revelation. I read Baron Wormser’s sharp and beautifully written essays here in VOX POPULI, even some of his poems, and admired his intellect and his mastership of thought and word. But this memory gave me so much more: the man, husband, writer, teacher, poet… I have to share this.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Rose Mary. Please do share Dawn’s beautiful tribute.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dawn Potter’s elegy (eulogy) is a masterly gateway to the soul and character of a poet. And to his genius.

I only knew him via his essays. But what works of art and insight they are. In an essay of his I read way back in 1991 (on Milosz), Baron said “It is better to live with doubt than strain for securities this century cannot provide….The denizens of the twentieth century, irresolute and submissive, are more concerned with dieting than with their souls….disavowing reverence.” Potter shows us his reverence for this world, and never seems to disavow it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Jim. Like you, I knew him only through his writing — which revealed a compassionate, intelligent and literate man. As I’ve argued elsewhere, he was the best of us.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He was the best of us. Now we can strive to make the best of him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an intelligent, passionate, and on-the-mark reflection about Baron, Dawn. He was one of our best, both as an artist and as a person.

LikeLiked by 3 people

He really was, Bob. There will never be another–

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dawn, what an extraordinary, deeply intelligent and moving piece — bravo to you, and thank you…

LikeLiked by 4 people

Laure-Anne, thank you . . . I know you also loved and respected him so much–

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you so much, Dawn, for this beautiful, articulate remembrance of our friend Baron— his “strict, almost ascetic tenderness.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

Jeff, thank you. I know how much he meant to you . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person