Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

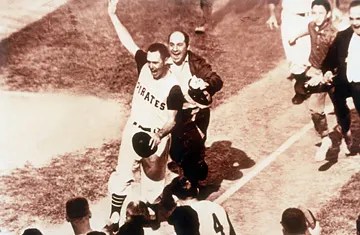

Joseph Bathanti: Maz’s Homer

~

Pittsburgh. 1960. October 13. A Thursday. In the final inning of what will be, by anyone’s measure, a mythic World Series, the hometown Pittsburgh Pirates battle a venerable unbeatable New York Yankees team that will go on to play in the next four World Series: Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Yogi Berra, Elston Howard, Whitey Ford, Casey Stengel.

Two months past my seventh birthday, I am in the second grade at Saints Peter and Paul School on Larimer Avenue, a street that cradles my family’s identity in the new world. Sister Ann Francis, my teacher, whom I do not like at all, though she will not prove the worst of them, slips us word that Sister Geralda, the ferocious school principal, who teaches eighth grade, has granted amnesty for the last ten minutes of the school day. We are to hurry home to witness the climax of the World Series.

Does Sister Geralda like baseball? I tend to doubt it, but I know nothing about her, nothing of what beats in her heart, nothing of what distinguishes her from the cruel and catatonic night face of the steely Allegheny River when our old Plymouth rolls across it over Highland Park Bridge. Nothing except that she paralyzes me with terror and, when I manage to cross her, she flails me unmercifully with a board.

Released, I run as fast as I can the entire way to my home on 430 Lincoln Avenue. My sister, a sixth grader, a kind and perfect girl, runs behind me. We blow in the kitchen door, whip by my mother into the living room, turn on the enormous Magnavox and fall into the couch.

Bill Mazeroski, a humble Polish-Catholic second baseman with the hands of a magician, leads off the bottom of the ninth for the Pirates. The score is 9-9. The seventh and final game of the deadlocked Series. The time is 3:36:30. Ralph Terry, the Yankees fifth pitcher of the day, is on the mound. Maz takes Terry’s first pitch for a ball, then cracks his next over the huge scoreboard in left field – still the only World Series-winning walk-off homer in baseball history – to win the World Championship for Pittsburgh. Church bells toll across the city.

Never in my life have I witnessed such unadulterated celebration, such unanimous joy. The citizens of Pittsburgh stay up all night, beating on pots and pans, singing and dancing. The tunnels leading in and out of the city are impassable for the mountains of newspaper and confetti. It is a moment by which I will measure the rest of my life.

That home run remains one of the mileposts of my consciousness, a Station of the Cross. Clearly a miracle. As numinous as the Burning Bush; or The Feast of the Epiphany (from the Greek: the appearance; miraculous phenomenon) which commemorates the “revelation of God to mankind in human form, in the person of Jesus” – when the wise men, Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar, showed up in Bethlehem. It is a Holy Day of Obligation.

Epiphany has also a decided literary valence. James Joyce, of course, “extended the meaning of the word”: a “sudden, dramatic and startling [moment] which [seems] to have heightened significance and to be surrounded with a kind of magical aura.”

On the day of that epiphanic home run in 1960, my father, a millwright on the Open Hearth at Edgar Thomson Steel Works in Braddock, the first steel mill that Andrew Carnegie erected in the United States, was six days away from his forty-fifth birthday. He would live to double that age and then some and, for all those years to follow, very nearly half a century, he claimed that he and I – my sister is curiously absent from his account – were at Forbes Field the day Maz launched his epic homer.

Not only that. My father also recounted, year after year, without wavering from the facts as he remembered them, the following narrative. As the Pirates came to bat in their end of the ninth, I stood and made a proclamation in a voice ethereal enough to somehow compel the attention of all 36,663 fans that day swelling Forbes Field. I imagine myself enveloped in a heavenly shimmer, a sudden eerie hush befalling the restive crwod, as they turned as one to where my dad and I sat in General Admission. I, a seven-year-old prophet, gave warning that Maz would hit it out on the second pitch. And then, by God, he did.

Well, I truly like my father’s version better than mine. It’s a great story, much better than what really happened. In it, I share the stage with what is arguably the most famous home run in the annals of baseball. Indeed, my father’s version elevates me to the story’s protagonist, a little seer who predicts miracles – nearly Messianic. And, I suppose, more than anything, I am flattered. It was a way for my father, a man who revealed through words little of what he felt, to reveal his love for me. In his version of that greatest day of all days in Pittsburgh Pirates history, the big story was not the 1960 World Series, nor Bill Mazeroski, nor the city of Pittsburgh. Nope. It was me, his only son, a measly seven-year-old, who emerged from it all a kid-prophet. “The version we dare to write is the only truth, the only relationship we can have with the past,” writes Patricia Hampl. Which is true – unless we accept others’ versions of the past. Like my father’s.

But my father’s version, if one may dispute a memory, is a figment. I was sitting on the couch next to my sister at our home on Lincoln Avenue. Yes, I watched that ball sail over Yogi Berra’s head and into Schenley Park. But I watched it on television.

Furthermore, my father would have never taken a day off from work to go to a ballgame. To do so, he would have lost eight hours pay, and forked out who knows how much for World Series tickets – an unimaginable luxury. He simply was not constituted thusly, period; and under no circumstances would my parents have allowed me to skip school for a ball game. I saw more baseball at Forbes Field with my dad than any other father-son duo I can drum up, but we were absolutely not at that one.

I don’t know how many times my father recounted that story over the years – dozens – but I never once contradicted him. As much out of love and respect as anything. My father was pretty much the nicest man I’ve ever met, and I can say in absolute truth – a word which this piece seems bent on discrediting – that he never once in the time we spent together on earth gave me a hard time unless I forced him into it. Not one gratuitous harangue or criticism. No meddling. I cannot remember once instance of his hurting my feelings. So, it just was not in me to spoil what he fervently believed and gave him such pleasure to recount.

Another thing: he never told stories. The Mazeroski-home run-prediction-story is the only story I ever heard him tell, and I felt honored to be in it. Because I never piped up to correct my father – nor did my sister, leg to leg with me that day on the couch, nor my mother, at the kitchen sink when Maz connected – my father’s version of that day became family canon. The more I heard him tell it – with an uncharacteristic passionate verve, attention to detail, narratively nuanced in every way, and never differing, version to version, year in and year out – the more I began to weigh the two versions, mine and his, in terms of verisimilitude – even though, again, his version was fabricated. Yet my dad is a supremely more credible source than I. Anyone who knew him would attest to this. I rely on lying. He had been forty-five and I a mere seven. Certainly, his age bestows an authority to his memory that a second-grader cannot claim.

Could I have possibly been at that game and somehow repressed that memory? Am I secretly clairvoyant? “ … not only have I always had trouble distinguishing between what happened and what merely might have happened,” testifies Joan Didion, “but I remain unconvinced that the distinction, for my purposes, matters.” Thus, it seems almost safe to say that I was there at Forbes Field that auspicious day, that I did rise and – in that gusty disembodied voice in Field of Dreams that announces “If you build it, he will come” – predict that Maz was going downtown on the second pitch out of Ralph Terry’s right hand.

In fact, I was there. The little Catholic boy: sacristan, acolyte, choir boy, in blue blazer with an emblem on his breast pocket of the Mater Dolorosa, white shirt and tie, next to a steelworker in a lime green asbestos jumpsuit and blue hardhat. That was me: the truant seven-year-old prognosticator people are still wondering what happened to.

Copyright 2013 Joseph Bathanti. From Half of What I Say Is Meaningless by Joseph Bathanti (Mercer University Press, 2013)

Joseph Bathanti was born and raised in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. His grandparents were immigrants from Italy and France. His working-class family included a steelworker father and a seamstress mother. After graduating from the University of Pittsburgh, Bathanti traveled to North Carolina in 1976 as part of a VISTA program focusing on prison outreach. He has continued to teach writing and hold workshops in prisons ever since. He was named by Governor Bev Perdue as the seventh North Carolina Poet Laureate, 2012–2014.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This memoir staggered me. I was 11, so in 5th grade in Houston, TX. Suddenly the classroom loudspeaker behind our teacher came alive from the principal’s office. It must have been 2:30, and to the amazement of our teacher, the game was on, ninth inning. The principal must must have held the mic up to the radio in their office. None of us knew why this unprecedented interruption was happening. The home run had not yet been hit. And then Mazeroski did his thing. That was the only time I remember that loudspeaker ever used except for the daily pledge of allegiance. I had forgotten that moment, so sweet.

The mighty Yankees done in by the “Hi-Rate” Pirates, as my baseball magazine wrote of that team. And Mazeroski the least likely home run hitter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maz and Clemente were the two greatest players for the Pirates.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for your kind comment, Magical Phantom. Johnny Blachard was catching thta day and, Yogi was indeed playing left field.

My best,

Joseph

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, Joseph. You rekindle a vivid memory! I was in my first, bewildered year at college, and although the Pirates were not my team, I rejoiced in their upset of the Evil Empire. I can still hear the wild call on my crackly radio. I was pretty miserable that year, but this was a great temporary boost.

One question, unless catcher Yogi B was somehow playing in the outfield, anything sailing over his head would have been a foul ball into the stands behind home plate.

A mere nitpick. This was great!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Syd!

LikeLiked by 1 person