Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

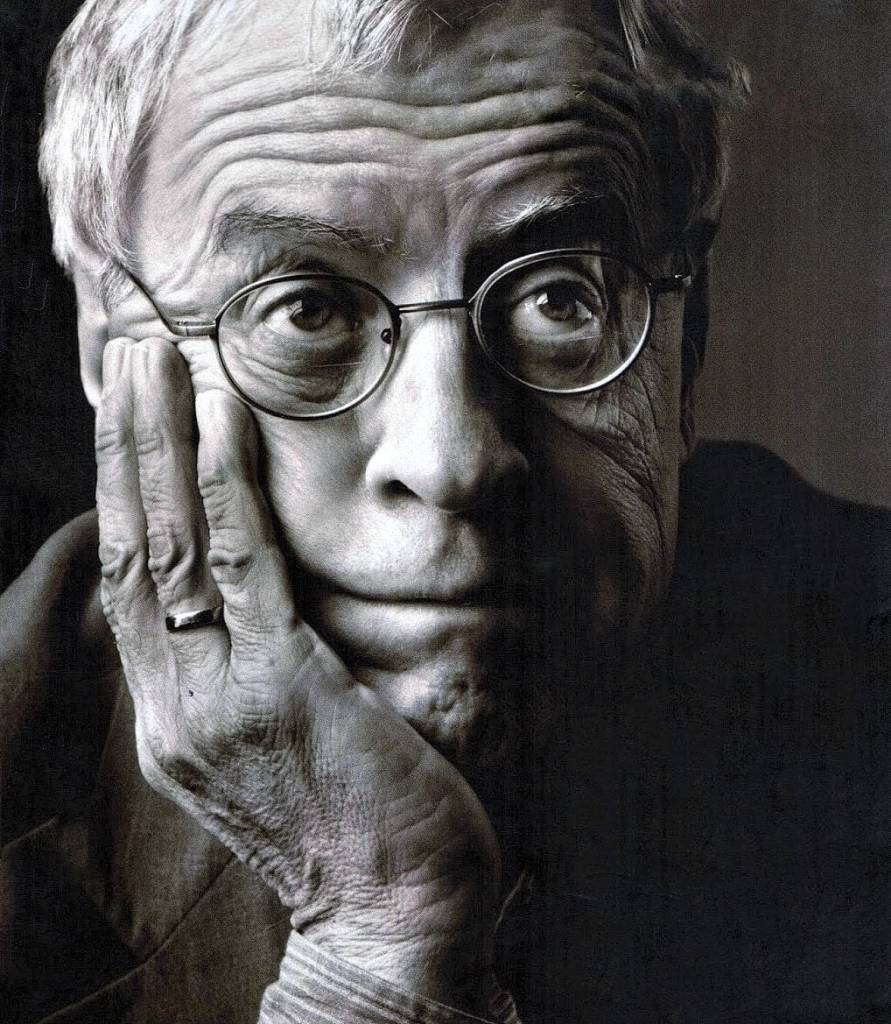

Mike Schneider: Appreciating Charles Simic (1938-2023)

A distinctive voice in American poetry for more than fifty years, Charles Simic died in January 2023. Much honored—a Pulitzer Prize, MacArthur “genius” grant, and a term as U.S. Poet Laureate—Simic was also remarkably prolific, and the close of his career simultaneously opens a door to assessing his sprawling body of work.

Since 1967, Simic published more than two-dozen collections of poetry, including translations of Eastern European poets. His nonfiction includes essay collections, a book-length meditation on artist Joseph Cornell, and a memoir in terse, colorful prose of his childhood—growing up in Serbia amid the violence of World War II.

This memoir, A Fly in the Soup, tracks Simic from his youth as a Serbian “displaced person” in postwar Europe—who spoke no English—to discovering himself in the mid-1950s as a writer in America. It provides biographical and historical context to help fill-out the often skeletal, sometimes near-cryptic bones of his voluminous poetry.

From A Fly in the Soup, we learn that Simic as a teenager emigrated from Belgrade to Paris, to suburban New York, to Chicago (Oak Park) for high school, and from there to Greenwich Village during the Beat era. Drafted in 1961, he re-visited Europe for a “tour” in the U.S. Army, and from there returned to New York City, where he met his wife and in 1967 earned his bachelor’s degree (in Russian) at NYU, eventually settling and raising a family as a literature professor at the University of New Hampshire.

“My travel agents were Hitler and Stalin,” Simic quipped more than once. Growing up in Belgrade, he survived bombardments from Germany, then the Allies—an atmosphere of violence and desperation that continued after the war—in conflict that led to Yugoslav communism under Josip Tito. Although Simic lived most of his life in the United States, his early experiences strongly inflect his work, which frequently features menacing imagery and an absurdist tone, for example (from The Voice at 3:00 A.M.):

CAMEO APPEARANCE

I had a small, nonspeaking part

In a bloody epic. I was one of the

Bombed and fleeing humanity.

In the distance our great leader

Crowed like a rooster from a balcony,

Or was it a great actor

Impersonating our great leader?

“The Americans are throwing Easter eggs,” Simic remembered his father shouting on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1944, when the Allies began bombing Belgrade [Fly, 11]. Years later he learned, irony piling on irony, that one of the egg throwers was Richard Hugo, then a bombardier on a B-24 Liberator, later an accomplished poet.

Hugo, wrote Simic, was deeply shaken at a 1972 writer’s gathering when their conversation uncovered this painful coincidence. Simic cast no blame. “We were two befuddled bit players in events beyond our control,” he wrote, adding, “I would have probably spat in the face of the dimwit whose decision it was to … bomb a city on Easter full of its own allies [Fly, 13].”

In June 1953, with his mother and younger brother, Simic migrated to Paris. The plan, ultimately successful, was to reunite with his engineer father who, having left Belgrade ten years earlier, had made it to America and found work. For a year in Paris, Simic occupied himself studying English by reading The Saturday Evening Post and Look [Fly, 64].

Despite having grown up amid the chaos of war and scarcity, Simic loved movies from an early age, especially American movies, and especially Buster Keaton. In Paris, he saw Singin’ in the Rain a dozen times [Fly, 59] and was captivated by Gene Tierney in the murder mystery Laura—her “cool, dark-haired slinky beauty [Fly, 60].”

Reflecting his love of movies, Simic’s prose in A Fly in the Soup has a cinematic quality, with colorful characters (many of them relatives), brushes with death, and stints in prison [Fly, 27], all lightened by Simic’s characteristic serio-comic tone. “My childhood,” he wrote, “is a black-and-white movie [Fly, 28].”

In June 1954, visas came through, and the three Simics shipped on the Queen Mary to New York. Simic’s first moments in America, greeted by the Statue of Liberty and the bustle of Manhattan, made a striking impression:

The trash on the streets, the way people were dressed, the tall buildings, the dirt, the heat, the yellow cabs, the billboards and signs … It was terrifically ugly and beautiful at the same time! I liked America immediately [Fly, 67].

Reunited, the family moved to Chicago a year later and found a third-floor apartment in Oak Park. Charles was seventeen and fluent in several European languages, none of them English. He attended Oak Park High, Ernest Hemingway’s alma mater. “The teachers reminded us every day”[Fly, 77]. Absorbed almost organically by Simic, the famed novelist influenced—more than usually noted—Simic’s terse, imagistic style.

Assimilating to life as an American teenager, Simic hung out at football games, drug stores and hamburger joints. “My greatest teachers in both art and literature were the streets I roamed [Fly, 80].” Chicago in the 1950s was still a factory town. “Its ugliness and squalor brought to mind Dostoevsky’s descriptions of Moscow and St. Petersburg slums [Fly, 79].” It was a place where Simic, decidedly not destined to be a pastoral writer, could flourish.

As he gained facility in English, he began to write poetry—mainly, he told one interviewer, because “I noticed in high school that one of my friends was attracting the best-looking girls by writing them sappy love poems.” In the process of writing poems that he soon realized were “stupid,” Simic said, he discovered “a part of myself, an imagination and a need to articulate certain things, that I could not afterward forget [Fly, 78].”

At a party he met novelist Nelson Algren, who advised him to forget Robert Lowell (whose work he was reading) in favor of Walt Whitman, Carl Sandburg, and Vachel Lindsay [Fly, 82]. Taking this advice, Simic grew to prefer less “academic” poets, and in August 1958, he moved to New York City, where he lived in a cheap Greenwich Village hotel, worked in a bookstore, frequented jazz bars and poetry readings, and communed with fellow writers at the Cedar Tavern. In an Eighth Street luncheonette, he read the sports pages and wrote more poems:

In New York on 14th Street

Where peddlers hawk their wares

And cops look the other way,

There you meet the eternal —

Con artists selling watches, silk ties, umbrellas,

After nightfall

When the cross-town wind blows cold

And my landlady throws a skinny chicken

In the pot to boil. Fumes rise.

I can draw her ugly face on the kitchen window,

Then take a quick peek at the street below.

[“New York Days (1958-1964),” Gettysburg Review (Summer 1998), pp. 374-75.]

He read almost continuously; as he wrote in an essay about being in New York during most of his twenties, “I am not exaggerating when I say that I couldn’t take a piss without a book in my hand.” [GburgR, 376]

His notions about what poetry was and could be exploded during this period when he found an out-of-print 1942 New Directions anthology of Latin American writing. It included Borges, Neruda, Vallejo, and others. “The folk surrealism, the mysticism, the eroticism, and the wild flights of romance and rhetoric in these poets were much more appealing to me than what I found among the French and German modernists that I already knew [GburgR, 377].” Simic began imitating the South Americans, leading to poems of brutalist imagery and geopolitical implications, in lines like these:

I’m the last offspring of the old raven

Who fed himself on the flesh of the hanged . . .

A dark nest full of misfortunes,

The wind raging above the burning tree-tops,

A cold north wind looking for its bugle. [GburgR, 377]

Simic’s internationalism led him to edit, with Mark Strand, Another Republic (Ecco, 1976), an anthology of European and South American writers that introduced American readers to poets such as Carlos Drummond de Andrade and Miroslav Holub and cast writers like Julio Cortazar and Italo Calvino in a new light. Over the course of his career, Simic’s internationalist enthusiasms led him to translate many Eastern European writers, including books by Vasko Popa and Tomaž Šalamun as well as anthologies such as The Horse Has Six Legs: An Anthology of Serbian Poetry (Graywolf, 1992).

In 1961, still in Greenwich Village, Simic came home one day at lunchtime, as he usually did, to check his mail for responses from journals; to his surprise and dismay, he found a draft notice [Fly, 124].Simic’s observations on what the Army calls “basic training” — similar to Kubrick’s in “Full Metal Jacket” — will resonate with many. “It’s amazing how quickly one turns into an obedient drudge in an army or a big company. It took me no time to realize that I was now a dog whose master carried a big stick [Fly, 126].”

For about 25-pages of A Fly in the Soup [126-51], Simic recounts his time as a military policeman in northern France. “I always hated cops and professors, and I ended up being both in life.” Some of his Army misadventures could be sketches for “Hogan’s Heroes” or “M.A.S.H.,” unsanitized for TV. Hanging out with soldier pals, he played cards and did “next-to-nothing,” with serio-comic episodes—including a suckling piglet in a French restaurant, sex with sheep (not Simic), a knife fight, a brief romance in Paris—ended because Simic didn’t want to be AWOL.

Despite his advanced education in indignity—to some extent, in fact, because of it—from his two years in the Army, Simic found his voice as a poet. Before being drafted, he had a “literary” image of himself, in tweeds and smoking a pipe; afterwards, back in New York, he felt humbler, and—as he said in a NYT review by Dwight Garner—haunted by painter Paul Klee’s remark that a young artist must find something that’s his own. It led him to write about even the simplest household objects with a kind of brutalist imagery, as exemplified by his classic poem “Fork” [Selected Early Poems, 1999]:

This strange thing must have crept

Right out of hell.

It resembles a bird’s foot

Worn around the cannibal’s neck.

.

As you hold it in your hand,

As you stab with it into a piece of meat,

It is possible to imagine the rest of the bird:

Its head which like your fist

Is large, bald, beakless, and blind.

By the time Simic won the Pulitzer Prize for his collection The World Doesn’t End (Ecco, 1989), he had published more than a dozen books, including a first volume of Selected Poems. With The World Doesn’t End, Simic turned another corner, escaping the exactness of line breaks into prose poetry, which in a subsequent essay he called “the monster child of two incompatible strategies, the lyric and the narrative.” The book’s title could be read as a comment on long-running discussions of prose poem form; why does it matter what you call it? might sum up his attitude.

He said as much in his 2019 Washington Post review of his friend and poetry colleague James Tate’s last book, Government Lake:

His [Tate’s] later work, written in prose, mixing realistic and fantastic elements, is made up of little stories full of poetry that tend to be as concise and tightly structured as verse. It didn’t make any difference to Tate what one called these pieces. He worked on them obsessively . . . .

The World Doesn’t End is dedicated to Tate, and—like his friend’s prose poems—Simic’s don’t linger in first person. Simic’s poetry in general, isn’t “confessional”—memories they draw on are products of the relatively impersonal forces of history. It’s hard to overstate how strongly such a perspective confronts the prevalent conception of poetry, then and now. “What makes James Tate’s later poetry unlike that of most American poets writing today,” wrote Simic, “is that it is rarely about him.”

With or without the “I,” nevertheless, poetry is inescapably personal, representing an individual field of experience and perception. It’s unlikely anyone who hadn’t lived through experiences such as Simic’s could write poems from The World Doesn’t End such as this:

The dead man steps down from the scaffold. He holds his bloody head under his arm.

The apple trees are in flower. He’s making his way to the village tavern with everybody watching. There, he takes a seat at one of the tables and orders two beers, one for him and one for his head. My mother wipes her hands on her apron and serves him.

It’s so quiet in the world. One can hear the old river, which in its confusion sometimes forgets and flows backward.

Like much of Simic’s poetry, this prose poem achieves its effects via elements of style associated with Surrealism—dream-like imagery, abrupt juxtapositions, and irrationality displacing conventional logic. Unsurprisingly, critics have often placed him with Tate and Russell Edson as practitioners of “American Surrealism.” Simic, however, persistently disavowed the label. As he told an interviewer in 1998:

I’m a hard-nosed realist. Surrealism means nothing in a country like ours where supposedly millions of Americans took joyrides in UFOs. Our cities are full of homeless and mad people going around talking to themselves. Not many people seem to notice them. I watch them and eavesdrop on them.

This hard-nosed realism, it’s worth remembering, stems from a childhood that included being bombed out of bed, among other strange occurrences. It provided Simic with a personal reservoir of bizarre, violent imagery consistent with surrealist practice. (Accordingly, one reviewer suggested that if not a Surrealist, Simic was a Serb realist.)

Despite disclaiming the Surrealist label, Simic embraced one of the group’s core principles—for discoveries in writing to occur by chance as opposed to conscious plan. In an essay titled “The Poetry of Village Idiots,”(from his essay collection The Life of Images), he wrote, “Others pray to God, I pray to chance to show me the way out of the prison I call myself. A quick, unpremeditated scribble and the cell door opens at times LI, 108].”

In another essay, “The Little Venus of the Eskimos,” he explained how wild phrases such as “the wheelchair butterfly” and “razorblade choir” (from James Tate and Bill Knott, respectively), don’t come from “leisurely Cartesian meditation. They are as much a surprise to the poet as they will be to the future reader . . . Metaphors and similes owe everything to chance.” [LI, 46-7]

With his doors propped open to chance, Simic also entertained frequent visitations from the comic muse, the one who bathes in the waters of irony. Reading a Simic poem and looking at his photo, a reviewer for The Guardian was struck by his “switchblade smile.” It’s not hard to imagine Simic as the wise-cracking guy in the back of high-school class, and he’d also be the best-read, smartest person in the room.

“Cut the Comedy” he titled an essay that espouses, of course, just the opposite—with observations about its necessary role in culture. “It is impossible to imagine a Christian or a fascist theory of humor.” [LI, 104] In an essay about Buster Keaton, he says that comedy “at such a high level says more about the predicament of the ordinary individual in the world than tragedy does,” and that true seriousness is inseparable from laughter [LI, 161].

Food—it goes with happiness. Few of us would disagree with Simic on this, or that as he put it, “The true muses are cooks.” [LI, 35] “One could compose an autobiography mentioning every memorable meal in one’s life,” he wrote [Fly, 152], “and it would probably make better reading than what one ordinarily gets.” In his poems and in essays like “The Romance of Sausages,” [LI, 171] Simic often wrote about the pleasures of food and drink, as in the opening poem of his 2015 collection, The Lunatic—as good a place as any to end this essay:

TODAY’S MENU

All we got, mister,

Is an empty bowl and a spoon

For you to slurp

Great mouthfuls of nothing,

.

And make it sound like

A thick, dark soup you’re eating,

Steaming hot

Out of the empty bowl.

_________________

Copyright 2025 Mike Schneider

Mike Schneider is a poet who lives in Pittsburgh. His sixth book, Friday’s Dance (Ragged Sky), is forthcoming in September. An earlier version of this essay appeared in Rain Taxi (Summer 2024).

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sometimes ( often) Vox Populi provides a glimpse of another life that feels more real than the one I have lived, a different one with poets, writers, poetry. This morning I finally leave my comfortable bed wondering ‘what if?’ It is not that I would exchange my children, garden, the ups and downs, but why did it take so long to find a place where I feel I belong—except the history—I can’t go back and add a lifetime of reading and listening and sharing poetry and now I rarely can make it to a reading. Ok, sorry, another pity pot rant.

LikeLiked by 2 people

No problem, Barb. Thank you for sharing these feelings. This is a safe place for all of us.

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this essay! I, too, will keep it for rereading. I didn’t know Charles Simic, but I had the pleasure of seeing/hearing him read once and talking to him afterward, while he signed The Monster Loves his Labyrinth for me. Also, that famous quote of his (“My travel agents were Hitler and Stalin.”) is the epigraph that opens the first section of my poetry book, Wild Flight, a section that is about my family history. At readings, when I include the opening poem of my book, I always introduce it with Simic’s words — seven words that perfectly describe my father’s “travels” too.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Oh dear Mike (and Michael) thank you for this! Charlie, Helen, Kurt and I were very close — as you know — for three decades, and I do, so often, miss our friendship. Thank you for this moving portrait of Charlie; I have copied and pasted your essay in my journal, to read it again from time to time. One of his books that is never far away from my desk is The Monster Loves his Labyrinth (excerpts from his notebooks). I never tire of it. Never tire of remembering how much Charlie loved food, friendship, long conversations about recipes and the absolute essential importance of sausages or heritage tomatoes… We spoke French together a lot — Helen was nostalgic of her/their life in Paris. He was warm, brilliant, funny, and, at times, fabulously witty and ironic, but always tender. And, oh, when you got him to talk about World politics & history! He loved his wife, Helen. Loved living quietly in the woods of New Hampshire. Loved his friends. We were lucky to be among them.

LikeLiked by 6 people

What a lovely reminiscence, Laure-Anne. Thank you!

>

LikeLiked by 3 people

Reading your comments about Simic, I immediately ordered The Monster Loves his Labyrinth. Can hardly wait. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The Monster Loves his Labyrinth–one of my favorite collections. By any writer. How lucky to have been friends for so long. I saw Galway Kinnell many years ago and he said that was one of a few true blessings in life: faithful friendship.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely true, Lisa.

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you very much, Laure-Anne, for this paragraph, filling in my rather academic essay from the distance of a reader who didn’t know Simic personally (although I briefly met him once) with your personal reminiscence. And thanks for mentioning The Monster Loves his Labyrinth, with which I wasn’t familiar. His work means more to me since I began to understand that he, essentially, has one foot in Europe always while the other is in the USA.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a brilliant essay by Mike Schneider. Hopefully this intro to Simic will inspire those who do not know Simic’s poetry or life to find him now. His books of prose are worth a read too:

Simic’s book on Joseph Cornell, the visual artist known for his assemblages in glass-fronted boxes, has encouraged me to mix media.

“The attentive eye makes the world mysterious”. Cornell in his book of prose pieces: The Life of Images.

His short poem, Country Fair, is a favorite poem of mine for its humor and dose of underlying irony. https://poets.org/poem/country-fair It’s neither Christian nor fascist.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I meant Simic, in his Book the Life of Images, not Cornell. Sorry

LikeLiked by 1 person

Simic and Cornell… fascinating connections.

LikeLiked by 3 people

So, so missed. Thanks for this x

LikeLiked by 3 people

Schneider writing about Simic. The perfect pairing!

>

LikeLiked by 3 people

I don’t know about this as a “perfect pairing” Michael, but thank you. I felt able to write about Simic only after coming across his prose memoir, A Fly in the Soup — which helps me enormously in appreciating the poetry. I’m interested now in reading more of his prose & going back (again & again) to his poetry.

LikeLiked by 1 person