Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Baron Wormser: What Nurtures Us, What Diminishes Us

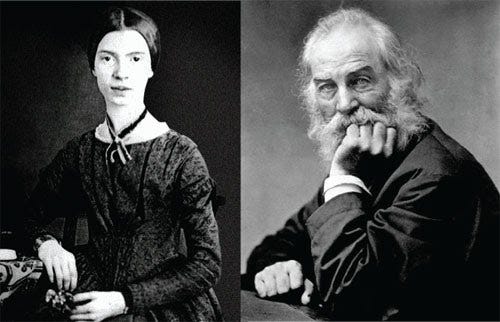

In a better world (clearly not this one), students who graduated from American high schools would take a course on the two nineteenth-century poets, Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, who represent pretty much everything there is to represent about this nation. Yes, others could be added, but, as figures who were at once real and mythic, they represent tendencies that run deep in the nation and, together, form a counter-weight to the political rhetoric that is always trying to determine what is American and who is American and what threatens the United States. My proposal is, of course, preposterous since immediately both poets would be called before the keep-our-schools-innocuous tribunals for personal matters that American youth should not know about – Dickinson’s failure to become a sanctified, come-to-Jesus churchgoer and Whitman’s sexual preference – as if biography were an arbiter of poetic value. But then poetry has no value in the eyes of the tribunals, be they local, state, or national. No need to pretend. Schools have better things to focus on. Like AstroTurf football fields.

What nurtures a people is culture, to which poetry is a prime contributor. Culture is spontaneous in the sense that it wells up from spirit sources – people who can articulate crucial, legendary senses of life that stem from the complexity of the society’s yearning, wondering, and intuiting. In small tribal societies these senses of life are codified over time in ritual, song, instruction, and prayer but also in life’s daily basics, such as growing food, cooking and eating, the literal culture that feeds each day. Societies that ignore the crucial place of wholesome food and well cared for soil are debased, no matter how many financial and scientific flags they wave. You cannot imagine Dickinson or Whitman shilling for an agribusiness that violated the earthy sense of life that was precious to each of them. That sense of life admits the centrality of sensitivity, a focus and an opening and a presence that is in every child who comes into this world. As we “grow up,” we more or less chortle about the loss of that sensitivity, which comprises one of those common scandals that passes as the way of the world and represents a deep loss of feeling, maybe the deepest. We look to love to redeem that loss and sometimes, in part, it may but the loss remains enormous. Poetry is the remembrance and avowal of that loss and is accordingly pushed aside.

In a society that feels something must be happening each moment, that some kind of fixing – however ill-conceived – is imperative, that considers progress, however ill-defined or woefully materialistic, to be the benchmark of meaningfulness, that celebrates its alienation in techno-distractions, the importance of culture as a counter-weight to the anxious spectacle of politics cannot be over-emphasized. It’s not a mystery that the United States is in the process of devouring itself from the inside-out, that the rampant incivility and ill-will constitute a sickness that is paraded as a virtue, though each day testifies to the cost of such behavior, not just in drug deaths, murders, and suicides, but in the reduction of human stature, the implication that goes with the ill-will, which is that people are worthless and that the creatures around people are worthless, too. The paradigm is plain: You welcome life, as the poets do and did, or you dismiss life in a slogan because you believe you know better. Life, however, has never needed “great” to be life.

The sad answer to the vicious dysfunction of politics has been to ramp up the importance of politics even more – pouring gasoline on the fire. The belief seems to be, in keeping with the tenor of modern times, that the society is perpetually in need of fixing, that the society has no functional, historical, Earth-bound memory, and that the fixing, which very much depends on who is labeling the problems as problems, can only be accomplished through politics, that other dimensions of life– spiritual, ecological, artistic – that mingle the private with the public are negligible. Enormous amounts of money are spent on elections that revolve around “issues” that are truly negligible because not much is really up for serious discussion: the so-called defense department keeps growing, the economic system is considered God’s gift to the planet, corporatism is the right hand of power, runaway technology is an undiluted blessing, secrecy is tantamount to security, a police state is desirable, and no one should have to give up anything – unless they are poor, which, according to the Gospel of Individualism, is their fault. The overall premise is that this show will go on forever, which tends to be a basic human premise, barring volcanic eruptions that darken the sky, asteroids, pandemics, and revolutions.

Societies live and die according to what they pass on to their young. If they have nothing of value to pass on, then they lose their sense of inherent purpose and must rely, as this one does, on acts of political will to make people feel something, however violently wrong-headed, is at stake. Traditional societies emphasize conduct of life – to use an old-fashioned, Emersonian phrase – in teaching their young: This is how we have done it and this is how we still do it because our conduct roots us in time, teaches us who we are, and makes us comprehensible to one another. We share in how we live. This is precisely what poetry, as essential discourse, can tell us since it considers the breadth and depth of not just our human days but the time that imbues the other creatures, to say nothing of the green world. Of necessity, poem-making is difficult because the poet is divining what must be said in a metaphorical yet available fashion. Through time, the poet enters the timeless. The sanity of poetry lies in this recognition of mystery. The indifference to sanity that characterizes so much politics, a refusal of sanity that has issued in wars, coups, forced emigrations, concentration camps, and arbitrary arrests among other nightmares, resides, both in the refusal of mystery, since mystery teaches awe and humility, and in the bluff assertion that some political “answer,” often of an ideological, conniving bent, offers something somehow of value.

In writing these words I would seem to be a long, if not laughable distance from the place of poetry, but I don’t believe that for a second. Poetry opens our hearts while it defends them. If a more important task is out there, I’m bound to wonder what it is. It is one among many strands in the medley that comprises culture but an ancient one, often uncanny in its perceptiveness. Dickinson epitomized that quality: “Alone, I cannot be – / For Hosts – do visit me – / Recordless Company – / Who baffle Key –” yet so did Whitman in his way: “For all that, and though the live-oak glistens there in / Louisiana solitary in a wide flat space, / Uttering joyous leaves all its life without a friend a lover near, / I know very well I could not.” Both are shrewdly alert and brimming with feeling, giving us signs of life we crave. Politics gives us rehearsed stances that derive their merit from their supposed weightiness and that accordingly convince us as they bludgeon us with opinions that are supposed to be more than opinions. The simple question “Says who?” that poetry asks over and over speaks to the dubious authority that brings us one crisis, often self-inflicted, after another. Surely some other forms of mystique can inveigle us beyond the bluster – for mostly it is bluster not vision or acumen but bluster – that recall how the first lesson is not some cock-eyed version of betterment. The first lesson is appreciation and the attentiveness that fosters appreciation, an attentiveness that draws its sagacity from the well of stillness.

Money, which drives the political show, has no interest in appreciation because money in its absoluteness runs over appreciation. The United States is particularly smarmy in this regard because the money impetus is coated with religiosity and the automatic assumption of virtue. One irony is that despite all the money spent on “security,” to say nothing of the nasty if not downright vicious policies that buttress that security, many Americans feel they are well-nigh invulnerable. They not only indulge all manner of political shenanigans and gross venality but they applaud them. Deeper circumstances of the sort that poetry has been engaging for millennia and that it continues to engage can go hang. Or so it would seem to the boastful present moment. The woman in her room in Amherst and the man walking around Manhattan knew better.

Copyright 2025 Baron Wormser

Bio

Baron Wormser was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1948. He grew up in Baltimore and went to high school at Baltimore City College and to college at the Johns Hopkins University. He did graduate studies at the University of California, Irvine and the University of Maine.

In 1970 he moved to Maine with his wife Janet. For twenty-five years he worked as a librarian for SAD 59 in Madison, Maine. Also he taught poetry writing at the University of Maine at Farmington. From 1975 to 1998 he lived with his family in Mercer, Maine, in an off-the-grid house on forty-eight acres. His memoir, The Road Washes Out in Spring: A Poet’s Memoir of Living Off the Grid, (see Books) concerns that experience.

In 2000 he was appointed Poet Laureate of Maine by Governor Angus King. He served in that capacity for six years and visited many libraries and schools throughout Maine. Also he read his poem “Building a House in the Maine Woods, 1971” at Governor Baldacci’s inauguration in 2003. (See Talks to read the poem.)

He currently resides in Montpelier, Vermont, with his wife. In 2009 he joined the Fairfield University MFA program. (See Talks to read his 2011 commencement address.) He works widely in schools with both students and teachers.

Wormser has received the Frederick Bock Prize from Poetry and the Kathryn A. Morton Prize along with fellowships from Bread Loaf, the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. In 2000 he was writer in residence at the University of South Dakota. Wormser founded the Frost Place Conference on Poetry and Teaching and also the Frost Place Seminar.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

15 comments on “Baron Wormser: What Nurtures Us, What Diminishes Us”

Leave a reply to Meg Kearney Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on July 20, 2025 by Vox Populi in Literary Criticism and Reviews, Opinion Leaders, Social Justice, spirituality and tagged Baron Wormser, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, What Diminishes Us, What Nurtures Us.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-qgsSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,948,424

When students state that “poetry is a political act,” I will send them to Baron’s essay– so they understand that writing poetry is essentially a life-saving act, a culture-saving act, a humanity & earth-saving act. And in that way, it is also a political (or an anti-political act), even if the poem itself is not “political.” …thank you, Baron!

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘Writing poetry is essentially a life-saving act, a culture-saving act, a humanity & earth-saving act….” Yes, thanks, Meg.

LikeLike

A teenager, I sat on the floor in my bedroom reading aloud: “I saw in Louisiana a live oak growing . . . .” Poetry was essential to my sanity and still is. Baron gets it and articulates the workings of poetry as well as anyone I’ve read. Thank you both.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant is the word–yes. This luminous essay is desperately needed now–I wish millions of us would read it.

I love this: “What nurtures a people is culture, to which poetry is a prime contributor. Culture is spontaneous in the sense that it wells up from spirit sources – people who can articulate crucial, legendary senses of life that stem from the complexity of the society’s yearning, wondering, and intuiting.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

For me the most important quote: “Money, which drives the political show, has no interest in appreciation because money in its absoluteness runs over appreciation. The United States is particularly smarmy in this regard because the money impetus is coated with religiosity and the automatic assumption of virtue.”

Brilliant – as always!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Betsy Sholl asked me to post this message: “Thank you for being so clear and sane, and for pointing out what happens to a country when it loses a sense of history and interiority. What’s left for people after an empire falls is culture.”

LikeLike

What a perceptive and brilliant response to where we are and what poetry does for. I have often Dickinson and Whitman symbolized two complementary, thought seemingly opposite, spiritual paths in American life and poetry. Wormer says this so much better! Thanks Baron Wormser and Michael!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for the strange skipped words in the above post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank YOU, Mary!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, what a gift this essay is! I will be sharing it widely. Many thanks, Baron Wormser, many thanks.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Christine. I love Baron’s essays as well.

M

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Baron Wormser is in my small circle of personal heroes. Though I have only met him on Vox. He always offers brilliant insights into the necessities of connecting poetry (and its cousins) with our lives, as we exist in this directionless culture that tries to stumble on without verse.

A day with a Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer poem on Vox, added to a Baron Wormser essay, is paradise on my screen. The beauty they both show and tell, and then turn to celebration, raises up a huzzah for today.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I too thought that Rosemerry and Baron were a good match for today’s reading. Thanks for noticing, Jim.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bravo! Thank you for saying everything I’d have said if I’d been as articulate as you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Baron is brilliant isn’t he? I love the way he brings these authors into our time….

>

LikeLiked by 2 people