Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Ted Olson: Bob Dylan and the creative leap that transformed modern music

~~~

The Bob Dylan biopic “A Complete Unknown,” starring Timothée Chalamet, focuses on Dylan’s early 1960s transition from idiosyncratic singer of folk songs to internationally renowned singer-songwriter.

As a music historian, I’ve always respected one decision of Dylan’s in particular – one that kicked off the young artist’s most turbulent and significant period of creative activity.

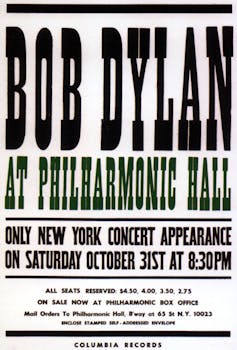

Sixty years ago, on Halloween Night 1964, a 23-year-old Dylan took the stage at New York City’s Philharmonic Hall. He had become a star within the niche genre of revivalist folk music. But by 1964 Dylan was building a much larger fanbase through performing and recording his own songs.

Dylan presented a solo set, mixing material he had previously recorded with some new songs. Representatives from his label, Columbia Records, were on hand to record the concert, with the intent to release the live show as his fifth official album.

It would have been a logical successor to Dylan’s four other Columbia albums. With the exception of one track, “Corrina, Corrina,” those albums, taken together, featured exclusively solo acoustic performances.

But at the end of 1964, Columbia shelved the recording of the Philharmonic Hall concert. Dylan had decided that he wanted to make a different kind of music.

From Minnesota to Manhattan

Two-and-a-half years earlier, Dylan, then just 20 years old, started earning acclaim within New York City’s folk music community. At the time, the folk music revival was taking place in cities across the country, but Manhattan’s Greenwich Village was the movement’s beating heart.

Mingling with and drawing inspiration from other folk musicians, Dylan, who had recently moved to Manhattan from Minnesota, secured his first gig at Gerde’s Folk City on April 11, 1961. Dylan appeared in various other Greenwich Village music clubs, performing folk songs, ballads and blues. He aspired to become, like his hero Woody Guthrie, a self-contained artist who could employ vocals, guitar and harmonica to interpret the musical heritage of “the old, weird America,” an adage coined by critic Greil Marcus to describe Dylan’s early repertoire, which was composed of material learned from prewar songbooks, records and musicians.

While Dylan’s versions of older songs were undeniably captivating, he later acknowledged that some of his peers in the early 1960s folk music scene – specifically, Mike Seeger – were better at replicating traditional instrumental and vocal styles.

Dylan, however, realized he had an unrivaled facility for writing and performing new songs.

In October 1961, veteran talent scout John Hammond signed Dylan to record for Columbia. His eponymous debut, released in March 1962, featured interpretations of traditional ballads and blues, with just two original compositions. That album sold only 5,000 copies, leading some Columbia officials to refer to the Dylan contract as “Hammond’s Folly.”

Full steam ahead

Flipping the formula of its predecessor, Dylan’s 1963 follow-up album, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” offered 11 originals by Dylan and just two traditional songs. The powerful collection combined songs about relationships with original protest songs, including his breakthrough “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

“The Times They Are A-Changin’,” his third release, exclusively showcased Dylan’s own compositions.

Dylan’s creative output continued. As he testified in “Restless Farewell,” the closing track for “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “My feet are now fast / and point away from the past.”

Released just six months after “The Times,” Dylan’s fourth Columbia album, “Another Side of Bob Dylan,” featured solo acoustic recordings of original songs that were lyrically adventurous and less focused on current events. As suggested in his song “My Back Pages,” he was now rejecting the notion that he could – or should – speak for his generation.

Bringing it all together

By the end of 1964, Dylan yearned to break away permanently from the constraints of the folk genre – and from the notion of “genre” altogether. He wanted to subvert the expectations of audiences and to rebel against music industry forces intent on pigeonholing him and his work.

The Philharmonic Hall concert went off without a hitch, but Dylan refused to let Columbia turn it into an album. The recording wouldn’t generate an official release for another four decades.

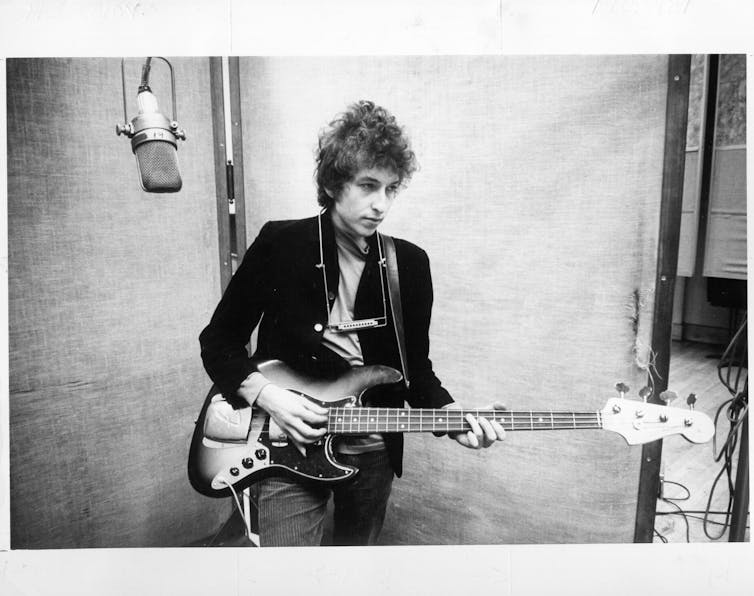

Instead, in January 1965, Dylan entered Columbia’s Studio A to record his fifth album, “Bringing It All Back Home.” But this time, he embraced the electric rock sound that had energized America in the wake of Beatlemania. That album introduced songs with stream-of-consciousness lyrics featuring surreal imagery, and on many of the songs Dylan performed with the accompaniment of a rock band.

“Bringing It All Back Home,” released in March 1965, set the tone for Dylan’s next two albums: “Highway 61 Revisited,” in August 1965, and “Blonde and Blonde,” in June 1966. Critics and fans have long considered these latter three albums – pulsing with what the singer-songwriter himself called “that thin, that wild mercury sound” – as among the greatest albums of the rock era.

On July 25, 1965, at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan invited members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band on stage to accompany three songs. Since the genre expectations for folk music during that era involved acoustic instrumentation, the audience was unprepared for Dylan’s loud performances. Some critics deemed the set an act of heresy, an affront to folk music propriety. The next year, Dylan embarked on a tour of the U.K., and an audience member at the Manchester stop infamously heckled him for abandoning folk music, crying out, “Judas!”

Yet the creative risks undertaken by Dylan during this period inspired countless other musicians: rock acts such as the Beatles, the Animals and the Byrds; pop acts such as Stevie Wonder, Johnny Rivers and Sonny and Cher; and country singers such as Johnny Cash.

Acknowledging the bar that Dylan’s songwriting set, Cash, in his liner notes to Dylan’s 1969 album “Nashville Skyline,” wrote, “Here-in is a hell of a poet.”

Enlivened by Dylan’s example, many musicians went on to experiment with their own sound and style, while artists across a range of genres would pay homage to Dylan through performing and recording his songs.

In 2016, Dylan received the Nobel Prize in literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” His early exploration of this tradition can be heard on his first four Columbia albums – records that laid the groundwork for Dylan’s august career.

Back in 1964, Dylan was the talk of Greenwich Village.

But now, because he never rested on his laurels, he’s the toast of the world.

Ted Olson is Professor of Appalachian Studies and Bluegrass, Old-Time and Roots Music Studies, East Tennessee State University.

First published in The Conversation. Included in Vox Populi with permission.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

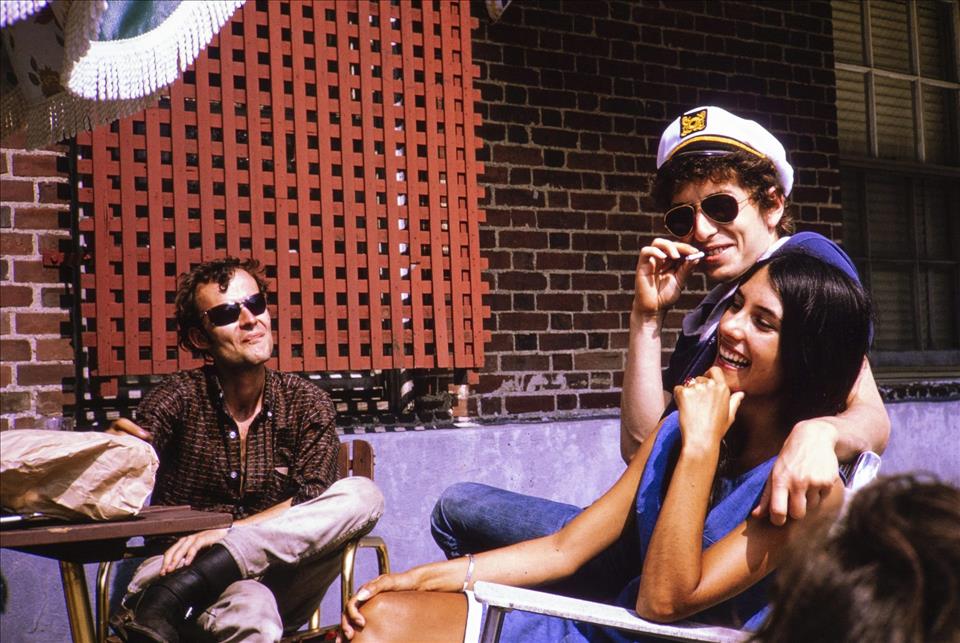

Regarding the photo at the top, Mimi Fariña was (as many folks know) Joan Baez’s younger sister, who married Richard Fariña. The guy is (I think) Bob Neuwirth, Dylan’s best pal then & for many years after. This time — ’64 Newport Folk Festival — is depicted in the new biopic, “A Complete Unknown,” which I saw last night & incidentally enjoyed much more than I thought I would.

Mimi is left out of the movie, as are many other people & events of that cultural time/place — c’est la vie. What a huge task to winnow so much material down to a coherent two-hour movie.

I especially enjoyed the music. Even though Bob himself doesn’t play or sing (some might say that’s a good thing, but I’m not one of them), the music is more than capably performed, and there’s plenty of it . . . great songs (mostly, but not all, by Dylan) from that amazing cultural moment (I almost wrote “awakening” — which I think applies as well.)

LikeLike

Geez, I forgot to mention — Dylan had a crush on Mimi, before taking up with Joan (or her with him), but Joan forbid her younger sis to speak to him. (According to David Hajdu, Positively 4th Street — good book about early years of Bob & friends.)

LikeLike

Thanks, Mike. I’m looking forward to seeing the movie.

>

LikeLike

I saw Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review in New Haven in 1975, when Joni Mitchell made her debut on the gig. I considered him my personal bard; my intrepid Homer whose iconoclasm nourished me, although I could not escape my own inner nihilism, or at least not then. I did, however, feel vindicated when, 40+ years later, he won the Nobel, much of which I wrote about in Five Points. It’s long but also a fun read. Here’s the link if anybody is interested:

https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=LitRC&u=googlescholar&id=GALE%7CA496645717&v=2.1&it=r&sid=LitRC&asid=05152c24

LikeLike

What a great essay, Matt. Thanks for sharing it. I like the authentic way you describe the under culture. M

>

LikeLike

Thank you, M. Thanks for reading. Merry Christmas

LikeLike

To us in Europe, Dylan came a little ‘second hand’. But, boy, did he erupt once we took notice!

LikeLike

I have never been a music fan; to this day most “music” irritates me. But, I remember playing Highway 61 Revisited over and over during the sixties. To me, Dylan isn’t a musician but a poet and storyteller and well deserving of the his Nobel prize for Literature.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I completely agree, Leo. Dylan is our bard, the poet/musician. I think of the Provencal poets and the traveling bards of the Bronze Age.

>

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes. I played it over and over, too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

At a Joan Baez concert at the Hollywood Bowl, one of the few concerts I went to, she introduced Dylan and had him play. I had never heard him before, being someone who spent hours with Lomax’s book to try to learn traditional folk music. At first I was disappointed. After all, I was there to hear Baez’s sweet ballads, but his distinctive voice grew on me ( I was also a fan of Dave Van Ronk and Jim Kweskin). I liked his early stuff best, but if I need to sit and remember, his albums are ones I turn to.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dylan is a giant in American culture, not only writing many iconic songs, but also creating the modern role of the songwriter/performer.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Barb,

There’s an album of Baez singing Dylan called Any Day Now. She turns him sweet, even as she focuses on some of his protest songs. She can be plaintive, and the album has its place on the Dylan cover spectrum.

The Byrds also covered him alot, and were into creating close harmonies from his stuff. It worked too. But, to me, the originals are the most powerful. He deserved the Nobel for his lyrics, not for his harmonica playing, btw.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve heard them. I always like the Byrds. For some reason I remember them on an old 8 track in Mexico or maybe on the radio?

LikeLike

In 1968 I snuck into a Byrds concert, sitting on the floor at the feet of their frontman Roger McGuinn, who was tricked out in black leather pants. When they performed Dylan’s song You Ain’t Goin Nowhere, the tune and lyrics transported me to another world.

Google the lyrics, and you will read:

Now Genghis Khan, he could not keep

All of his kings supplied with sleep

We’ll climb that hill, no matter how steep

When we get up to it

I still haven’t gotten up to it, But Dylan gets me close.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I often prefer covers of Dylan songs to his versions. But BD is the real thing.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person