Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Mike Vargo: Magical Realism — in Literature, in Life, and Online

What does your mind think of your body? Mine enjoys mine, mostly, but keeps trying to escape it.

This odd situation is a byproduct of the mind-body problem, long debated by philosophers: the question of how two very different entities coexist and relate within a person. An obvious difference is that the body is physical while the mind seems not to be. But I would ask you to consider a more consequential difference. While the body is finite and constrained, the mind wants to expand and explore without limits.

The body does have one advantage. Since we are animals, the experiences that make us feel most alive are physical — the taste of an orange, a lover’s touch, the swell and scent of the sea. We pay money to have our bodies ratcheted high in the air and dropped through swooping loops in roller coasters. And yet, as vivid as these experiences may be, the mind has a further agenda. Each of us longs to transcend the limited, personal self.

We’re probably born with this longing. Think of how children play. They play at being dinosaurs, mythical creatures or whatnot. My daughter called herself Dark White Wolf, and when I was a child, I had an imaginary companion — a second self — whom I brought to the dinner table with me. Nobody was allowed to sit in my doppelgänger’s chair.

As we mature, these fantasies may come less often, in forms less “childish” than before. But they never go away. We want to break the bonds that confine us to a single presence, with a single field of vision and field of feeling. We want to cast our presence wide and far — perhaps by achieving unity with the numinous All. Or by somehow capitalizing on it for glory and gain.

**

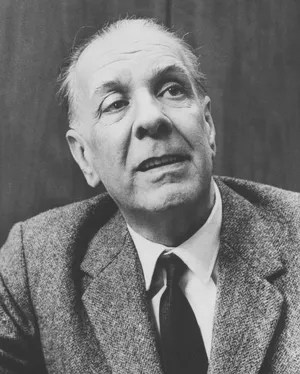

Borges would have understood. The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) was an early master of South American magical realism. His short story “The Aleph,” published in 1945, echoes across the decades from that modern-but-primitive time.

The setting is a genteel old house in Buenos Aires. Borges writes that in a series of visits, he’s formed an uneasy friendship with the man of the house, a minor public official named Daneri. The friendship is uneasy because Daneri, though a gracious (and loquacious) host, peppers people with his pedantic pompousness. He fancies that he is a great poet soon to be discovered.

Over cakes and cognac, Daneri declaims passages of the magnum opus he’s been working on. Crafted in galumphing lines of tangled language, it is an epic poem ambitiously titled The Earth. Per Borges:

“Daneri had in mind to set to verse the entire face of the planet, and, by 1941, had already dispatched a number of acres of the State of Queensland, nearly a mile of the course run by the River Ob, a gasworks to the north of Veracruz … and a Turkish baths establishment not far from the well-known Brighton Aquarium.”

Behind the utter absurdity of the venture, a mystery lurks: where does Daneri get his material? How would a sedentary, citified egghead know what those faraway realms look like? Turns out he has a secret source. Down in the basement of Daneri’s house — a dark, dingy little cellar — a spot along the edge of a step in the wooden staircase happens to be the Aleph. The Aleph is “the only place on earth where all places are,” a point in space “that contains all other points.”

Finally Borges is invited to view the Aleph. Told where to look, and left alone in the darkness, he notices “a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance.” Then, peering into it, Borges is overcome with awe:

“I saw the teeming sea; I saw daybreak and nightfall; I saw the multitudes of America; I saw a silvery cobweb in the center of a black pyramid … I saw the slanting shadows of ferns on a greenhouse floor; I saw tigers, pistons, bison, tides, and armies … I saw horses with flowing manes on a shore of the Caspian Sea at dawn; I saw the delicate bone structure of a hand; I saw the survivors of a battle sending out picture postcards … I saw my own face and my own bowels; I saw your face; and I felt dizzy and wept …”

The reverie is broken when Daneri opens the cellar door and calls down from above. Brimming with glee, he raves about the “one hell of an observatory” he’s shared with his guest — an observatory that he, Daneri, believes he has been granted so that he can write his soon-to-be-famous epic.

**

Lately, “The Aleph” has become a cult favorite of some readers in the tech community. They see the 1940s tale as a foreshadowing of today’s cyberculture. We now have an actual equivalent of the Aleph. The internet is the place where all places are. Pundits complain about the distractions of the screen, about people getting addicted to the trivia displayed there. But maybe we are driven to the screen by the same longing that the artist Damien Hirst expressed in the title of his 1998 book: I Want To Spend the Rest of My Life Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now.

On the internet you can do that. Or at least a facsimile of it. You can see what your friend is having for lunch at a cafe in Chicago; listen to a standup comic in Lagos; travel back in time to when James Baldwin debated William F. Buckley Jr. (YouTube has a vintage video), and get wellness advice from persons who look weller than you.

One night recently I talked on the phone with someone who’d just been to Vila Franca de Xira in Portugal, a small city near Lisbon, along the shores of the river Tagus. As the caller described various adventures, I followed on my Macbook screen. Google Street View was ideal for clicking along the route of my friend’s bicycle ride. The ride had started with a tense crossing of a high-traffic bridge over the Tagus — a cyclist myself, I could almost feel the shudder of trucks and cars speeding by — and then once the bridge was past, I could sense the ease and exhilaration of cruising quiet roads through airy countryside.

This was not the same as being there. The Macbook can only give me ghostly hints of how it feels to be in Portugal. But the hints are enticing enough and rich enough to induce an out-of-body experience — the perception, the illusion, that I am in places far from where my body is. And an endless variety of such experiences are right at hand if I care to chase after them. At any moment, my electronic Aleph offers a vastly greater range of perceptions than I can find in my room at home or nearby.

***

The lure of the large: There’s always the hope that in an astoundingly large space, everything you are looking for must exist somewhere. If I keep searching I will find the perfect mate, the perfect job, the shoes that feel just right. The hope doesn’t even have to be specific. A vague discontent will do: I don’t know what my problem is, but the solution must be out there.

Another Borges story, “The Library of Babel,” imagines a library so immense that people suspect it may be infinite. The books in this library contain every possible arrangement of the letters of the alphabet and common punctuation marks. Most are nonsense; they consist of words like dhcmrlchtdj and have titles like Axaxaxas Mlö.

Some librarians of Babel, appalled at the staggering number of nonsense volumes, have destroyed huge stacks of them. As Borges points out, the book-burning doesn’t help much. For every nonsense volume eliminated, there are hundreds of thousands that differ from it by only a single character. And billions that differ by a few more.

Perversely, this fact raises hope. You don’t need to find the one book that has the exact, pristine text of Klara and the Sun. A copy with occasional typos should be quite readable. If you’re lucky you might also find a good-enough copy of a novel that will be a bestseller ten years from now, and you can read it first. But in any case the odds are astronomically against you. As are the risks of being misled.

If you’re tempted to search for the catalogue of the Library of Babel, be advised there are myriad false catalogues. The library would have versions of Moby-Dick in which Ahab survives the voyage and earns renown as the first peg-legged pitcher to win a World Series game. There would be corrupted versions of Barbara Tuchman’s history The Guns of August, which cite nonexistent evidence to prove that World War I did not occur. And of course deceptions abound on the internet, too. The profile of your perfect mate has been falsified. Scams grope at you from every corner and real events are written off as hoaxes and hoaxes are presented as real.

But perhaps you don’t care about fidelity to real life. Perhaps you are looking for an alternate universe where your wildest dreams can take flight — because you perceive your own real life to be woefully inadequate.

Your body is a flimsy bag of flab and stray hairs, of headaches and stomach churn. Career-wise, you made a wrong turn years ago. The diploma on the wall and the little mementos on a shelf are scant rewards for years of effort; the rest of your home is cluttered with junk that has no meaning.

So you plunge into the web. It’s a sticky web, good for catching human flies.

**

Confession. The research for this essay included many hours spent wasting time online. That part was easy. I’ve had plenty of practice. The hard part has been finishing the essay.

My mind rebels. It refuses to admit that the act of writing — simply staring at words already on the page, and placing fingers on the keyboard — can, in itself, be a process of discovering the words that ought to come next. The process feels too much like work. It feels too limiting.

Besides, fears and doubts creep in. For example, the fear of not saying anything people will care to read. My memory replays what the Duke of Gloucester allegedly said to Edward Gibbon about The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: “Another damned fat book, eh, Mr. Gibbon? Scribble scribble scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?”

Gibbon wrote voluminously but narrowly, as if with blinders on. While composing the book, all that he studied and thought upon was his subject. My mind recoils from such a trap. Instead it believes the Answer with a capital A is out there, waiting to be found, so it browses randomly on and on.

Can the mind, in its quest to escape limits, become self-limiting?

Mike Vargo is an independent writer and editor based in Pittsburgh. Quotations from “The Aleph” are given in the English translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni.

Copyright 2024 Mike Vargo

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Well, all of you said it all. There is nothing to add. Except to remind everyone that in quite a number of (red) States, they’re banning books. Perhaps they’re on to something? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This brilliant essay articulates the reasons the essay I’m currently writing/not writing is taking so damn long! These truly are the “days of miracle and wonder” but sometimes I wonder if the changes to our human consciousness are moving us to a brighter future or a kind of extinction, a death-in-life in which we can’t focus on anything: Antaeus unable to touch the earth loses all his strength. Universal Aleph-induced ADHD?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know what you mean, Richard. I make use of technology, but I’m afraid of it, especially AI.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant essay. A whole symposium could be held around its many contours. One thought: Perhaps we will soon have degree programs called MCAs instead of MFAs. (you can get a Masters in Conspiracy Arts, and write your own conspiracy). The Dean will be a bored billionaire. Magical Realism on dirty steroids. Pixilated doppelgangers.

It brought back a memory: for our first class in my graduate library science program in 1976, we read three pieces as an intro. to what we were about to undertake in our careers: 1) Borges’s Library of Babel, the result, we were told, of a library without compassionate gatekeeper librarians to select and winnow, 2) HG Wells writing about a World Brain, which would contain all knowledge. The lesson for us: it was soon coming with computer technology, and we librarians could be the leaders in using it for democratic enhancements of life, 3) an article about the panopticon, a prison system designed so surveillance would be universal and ubiquitous, with the implied danger for us all of such a complete dystopian usage of information as the World Brain might create.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Jim, out of the hundred thousand or so comments and responses in Vox Populi over the last ten years, this one of yours is my favorite. We are very fortunate to have your clarity of thought and felicity of expression to read every day. Bravo!

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’m tearing up. Just trying to pass on wisdom from those who taught me. Vox Populi is a blessing.

LikeLiked by 1 person