Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

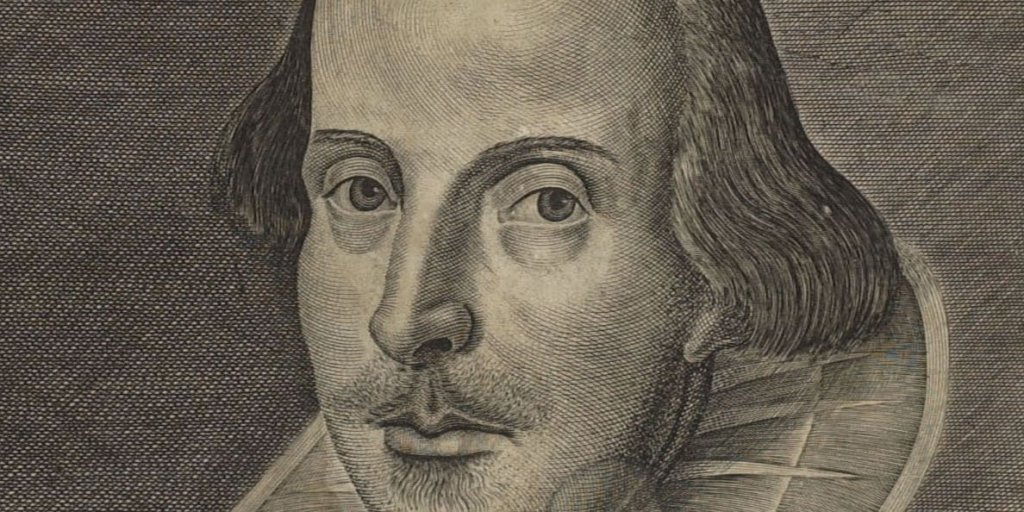

William Shakespeare: Sonnets 73 & 74

Sonnet 73

The poet describes himself as nearing the end of his life. He imagines the beloved’s love for him growing stronger in the face of that death.

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

~~

Sonnet 74

In this sonnet, which continues from s. 73, the poet consoles the beloved by telling him that only the poet’s body will die; the spirit of the poet will continue to live in the poetry, which is the beloved’s.

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away,

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee.

The earth can have but earth, which is his due;

My spirit is thine, the better part of me.

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead,

The coward conquest of a wretch’s knife,

Too base of thee to be rememberèd.

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

Public Domain. Source: The Folger Shakespeare Library

For a short biography of William Shakespeare, click here.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sonnet 74 features the term “bail” and makes me wonder just how far back that goes. I drove by a Bail Bondsman “24/7” two days ago on my way home from the County Landfill Transfer Station. How long we’ve been at certain things—eh?

LikeLiked by 1 person

From OED:bail (n.1)

“bond money, security given to obtain the release of a prisoner,” late 15c., a sense that apparently developed from that of “temporary release (of an arrested person) from jail” (into the custody of another, who gives security for future appearance at trial), which is recorded from early 15c. That seems to have evolved from the earlier meanings “captivity, custody” (late 14c.), “charge, guardianship” (early 14c.).

The word is from Old French baillier “to control, to guard, deliver” (12c.), from Latin baiulare “to bear a burden,” from baiulus “porter, carrier, one who bears burdens (for pay),” which is of uncertain origin; perhaps it is a borrowing from Germanic and cognate with the root of English pack, or perhaps from Celtic. De Vaan writes that, in either case, “PIE origin seems unlikely.”

To go to (or in) bail “be released on bail” is attested from mid-15c. In late 18c. criminal slang, to give leg bail meant “to run away.”

also from late 15c.

bail (v.1)

“to dip water out of,” 1610s, from baile (n.) “small wooden bucket” (mid-14c.), from nautical Old French baille “bucket, pail,” from Medieval Latin *baiula (aquae), literally “porter of water,” from Latin baiulare “to bear a burden” (see bail (n.1)).

To bail out “leave suddenly” (intransitive) is recorded from 1930, originally of airplane pilots. Perhaps there is some influence from bail (v.2) “procure (someone’s) release from prison.” Related: Bailed; bailing.

also from 1610s

bail (n.2)

“horizontal piece of wood in a cricket wicket,” c. 1742, originally “a cross bar” of any sort (1570s), probably identical with French bail “horizontal piece of wood affixed on two stakes,” and with English bail “palisade wall, outer wall of a castle” (see bailey). From 1904 as the hinged bar which holds the paper against the platen of a typewriter.

also from c. 1742

LikeLiked by 1 person

Someone once said: “I first thought the dictionary was simply a poem about everything.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like something our friend Barbara Hamby would say.

LikeLike

This sonnet (“That time of year thou mayst in me behold”), as many readers know, is a classic example of iambic pentameter. Galway Kinnell once upon a time quoted it from memory to me & a few others in a workshop — oh boy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The opening line of #73, as many readers know, is a classic example of iambic pentameter. Once upon a time, Galway Kinnell quoted this sonnet to me (& few others) from memory . . . in a workshop, oh boy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The opening line, as many readers know, is a classic example of iambic pentameter. Once upon a time, Galway Kinnell quoted this sonnet to me (& few others) from memory . . . in a workshop, oh boy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These very lines came to mind this week while driving. Thank you for posting them here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anyone could write, “I’m like the fall.” Only Shakespeare could write, “

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang.”

Thanks for these lovely sonnets. Every time I read Willie, I write better poetry.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks, Charlie. Shakespeare has spoken to me since I first read him in Mrs Ashton’s class in the tenth grade. I’m an old man now, and these particular sonnets about aging mean everything to me.

>

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’ve long loved sonnet 73, partly for the way it seats so well in memory. Was not familiar with 74, I admit, but find this deepening a welcome discovery. Thanks once more.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Luray. I usually think of each of the sonnets as a discrete utterance, so in this case I thought I’d post two that appear together and, at least to my ear, speak to each other.

>

LikeLiked by 3 people

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

Just these lines — these will sing in me all day.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, me too.

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang…

This timeless line summarizes the early stages of my grief, and I suppose, that of many others.

As the sonnets were commissioned for the young man, it might reasonably be assumed that he’s the addressee who’s the intended audience. However, being a sleight of hand kind of guy, Shakespeare might have had others in mind as well; the darlings of his heart might encompass several , and the readers, if the sonnets were intended to be shared: the royal you, the multitudes of us readers.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, anything we say about Shakespeare the man is pure guesswork.

>

LikeLiked by 4 people

73 sad but beautiful. I wonder if the Bard is referring to his dark lady or his young man in the “you”?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Scholars believe that the first 126 sonnets are addressed to a young man; the last 28 are either addressed to, or refer to, a woman. So these two sonnets are spoken to a young man, presumably Will’s lover.

LikeLiked by 4 people