Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 20,000 daily subscribers and over 8,000 archived posts.

Baron Wormser: Agony

I grew up Jewish in Baltimore after the Second World War. I had a bar mitzvah but my parents were not especially religious. As in the movie Diner, the Baltimore Colts were as much a religion as anything I encountered. When they left Baltimore, I hoped a curse would follow them. I apparently retained a religious disposition in my genetic make-up. The Old Testament was never old.

The agony I feel about the events in Israel, an agony shared by millions around the planet, many of whom may never have entered a synagogue, is very real. I wake up at night and lie there, held fast by grief, impotence, anger, and despair. My legs ache, which is where stress goes in my body. I feel as though I again am living through the war in Vietnam where I also was assailed daily. So much for fifty years and the wars I have witnessed at a distance.

One hell creating another hell would be the gist of the events, also known as “history.” I dare say many of us know that, however much we try to push that gist away and put a hope-against-hope face on it. Since, one way or another, we are born into the events, such hope makes sense. I have come to feel, however, that a deep dishonesty resides in the messianic religions, one that continues to thwart the human race even as it seems to console them and raise them up. I mean the agony in the religions that is, at once, central and secondary, an agony that is purged by the tribal ethos and by, respectively, the Messiah and the Prophet, yet never goes away. “Why hast thou forsaken me?” The echo remains.

Given the monumental facades of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, any quarrel with them is a waste of time. I realize that and, actually, I have no quarrel. What I have in my mind are the images of dead children. I look to the religions to tell me about the dead children and find that they have fostered this carnage, that intransigence goes with religious doctrine—this not that. The prohibitions and strictures are many. Wrath is right around the corner. The events in Israel come as no surprise in that regard. Mutual incomprehension among the various sects goes a long, unhappy way down a long, unhappy road.

As a Jew in Baltimore I grew up with the movie Exodus and its song: “God gave this land to me.” I received Israel bonds on the occasion of my bar mitzvah and, more to the point, began to read about the Shoah. When, later, I started to seriously write poetry, one of my first poems was about someone who read so much about the Shoah, she committed suicide. Agony piled on agony. Something in me became wary about human beings and has never gone away. I don’t rue that.

The tribal, messianic religions vanquished the pagan, polytheistic outlook. Each person under the monotheistic reign had a soul that was imbued with God’s spirit, to say nothing of redemption, salvation, heaven, and miracles. The Greeks, to cite one pagan locale, certainly knew what agony was. Their theater is replete with it as are their legends. At the end of a tragedy the agony has been voiced but has not abated. No miracle intervenes. Fate remains fate; the human situation remains very bounded. Pathos attends those boundaries but so does the hubris of warrior cultures.

The story of Abraham and Isaac, to cite one agony story, ends with obedience being rewarded. This is not exactly a glad ending but it is an edifying one. The Hebrew God demands what He demands. Humankind, as represented by a man, Abraham, believes and acts accordingly—no matter what the consequences. A sacrifice must occur. Obeisance must be paid. The gap between the human and the divine is a chasm and must be bridged by some sign. The Greeks believed in sacrifices, too. For people it seems a sort of insurance, as in: “Look at what we are doing for you.” Is God looking? Are the gods looking? The stories said so. Once.

To say humankind has been haunted by those questions would be a substantial understatement. On one hand lies the agony of doubt; on the other, the confidence of faith. Prayer is literally the joining of those hands. Though a great amount of energy goes into connecting with the divine, the burden of bearing up remains in the human realm. People are a great deal less than divine. To be sure, various groups have aspired to holiness and godliness. A measure of their aspiration is how many of those groups have persecuted others in the names of holiness and godliness. Perhaps when a religion is founded on divine communication, anything after that is a letdown. Living with that letdown is the task of organized religion. The miracles were once there—the accounts are truly revelatory. Meanwhile, believers can rest assured in their particular God-slant.

The abolition of fate paved the way for progress. A large human vista, however exploitative, to say nothing of vicious, was opened. This change can be seen in Shakespeare’s tragedies where the specter of fate is just that—a specter. The individual personality is on display, not as a fate-bound hero, but something else, a more-or-less free actor. Hamlet is responsible to a ghost; Othello listens to Iago. These terrible tugs show that doom comes in various forms. The individual pays the requisite price—his death. Such tragic extremity gave way to a much more cushioned life, all that came to be connoted by “modern,” to use a prime descriptor. Those who are directly involved in the tortured scenarios of Israel and Palestine are beholden to modernity as, among other things, their weapons, as instances of technological progress, testify.

Yet they are beholden to their very long-standing religions, too. It is hardly a coincidence that the current events are occurring in such a holy place. The pull of religious time, the gravity of the Torah, the New Testament, the Quran, is immeasurable. It would seem to abolish time but doesn’t. The nation-states very much exist in real time, whether they are ruled by elected leaders, kings, or mullahs. The whole fallible scenario we call “politics” is on display, the attempt to justify expediency, even as history lurks not very far in the background insisting on its prerogatives: This land is mine.

Though the messianic religions have made a show of humility before God, the conceit of being special, of being singled out, remains. So does an indifference to the earth and the female dimension that goes with that. To make everything into One is a grand feat but a blinding one at the same time. The One can justify most anything since everything must be incorporated into that One. It is easy to feel in the actions that result in the murders of children that too much surety is at work. Also too much agony, an agony that shows no sign of going away in the near future. The stakes are too high. God, in his various dispensations, said so. Heeding Him is paramount.

Even the United States, a distinctly un-ancient nation-state, prides itself as being one nation under God. One wonders if all this evocation pleases the Lord. Many citizens live without Him and find other forms of spirit to make their lives meaningful. Or they fall into the throes of meaninglessness. God has saved many such people from such falls. Whether the price of salvation is worth paying is a question humankind will never answer. It falls under the category of drama that the pagan Greeks were so good at. They had a perspective on human affairs that we lack. They, too, were at war a good deal of the time. They, too, put people to the sword but not in the name of God. It seems that human decency—the way of kindness—has never attracted a large following. As it is, I have my agony or, to put it more accurately, it has me.

Copyright 2024 Baron Wormser.

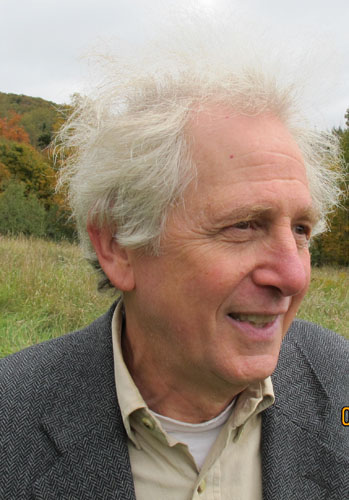

In 2000 Baron Wormser was appointed Poet Laureate of Maine by Governor Angus King. He served in that capacity for six years and visited many libraries and schools throughout Maine. His books include The History Hotel (CavanKerry, 2023).

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- More

Related

10 comments on “Baron Wormser: Agony”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on January 21, 2024 by Vox Populi in Health and Nutrition, Opinion Leaders, Personal Essays, Social Justice, spirituality, War and Peace and tagged Agony, Baron Wormser, Gaza, genocide, Israeli-Palestinian conflict, pacificism, The History Hotel, Vietnam War.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-meMSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,657,006

“It seems that human decency—the way of kindness—has never attracted a large following.”

That’s true, and let us still heed what Rousseau said, “What wisdom can you find that is greater than kindness?”

LikeLike

Always enjoy reading his pieces

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I love Baron’s essays. Very clear, passionate, precise prose about big topics.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another masterpiece of clear thinking.

“They, too, were at war a good deal of the time. They, too, put people to the sword but not in the name of God. It seems that human decency—the way of kindness—has never attracted a large following. “

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Rose Mary. By the way, I love your sonnet published recently. It’s a pleasure to know such accomplished writers.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is what spoke loudest when I teac the piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops. My hand and brain are not working together. I meant when I read this piece.

LikeLike

Among the many keen insights of this essay, is one behind the scenes:

our human need for equilibrium. I first learned this from my mentor/hero Etty Hillesum. Wormser too, writes of the dichotomies of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and the need many followers wrestle with, in how to reconcile them, hopefully in loving ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well-said, James. Thank you.

>

LikeLike

Just one more, before I go

😘😘😘😘

Tim Mayo

http://www.tim-mayo.net

LikeLike