Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Mike Vargo: ‘Cat’s Cradle,’ Community, and Fascism

Maybe Bokonon had a point. Bokonon, for those not familiar, is a character in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle. On a fictional Caribbean island, a holy man lives in the mountains. He is rarely seen, but the island’s people follow the religion he has created, Bokononism. The narrator of Cat’s Cradle — a visitor who converted to Bokononism — explains its concepts. For instance:

“We Bokononists believe that humanity is organized into teams, teams that do God’s Will without ever discovering what they are doing. Such a team is called a karass by Bokonon.”

There are also false karasses, groups that appear to be meaningful but are “meaningless in terms of the way God gets things done.” A false karass is a granfalloon (rhymes with grand balloon). One character in the novel is a woman from Indiana who’s always eager to bond with fellow Hoosiers. And Hoosiers, we are told, constitute a “textbook example” of a granfalloon. Other granfalloons include corporations, political parties — “and any nation, any time, anywhere.”

Fiction isn’t true, but some say it can point to truth. I am a nonfiction writer, a prosaic guy, tethered to what used to be called facts. Please bear with me while I tell you why I’m tempted to be a Bokononist.

Of course it would be tricky to apply the concepts to real life. Although corporations, parties, etc. may count for nothing in God’s eyes, they can have quite an impact on us mortals. And who knows what God’s Will is, anyway? Yet I believe that we are organized into real and less-real communities — with a community defined, rather loosely, as a group of people that you feel you’re a part of and to which you belong. I happen to live in one that’s sort of unreal.

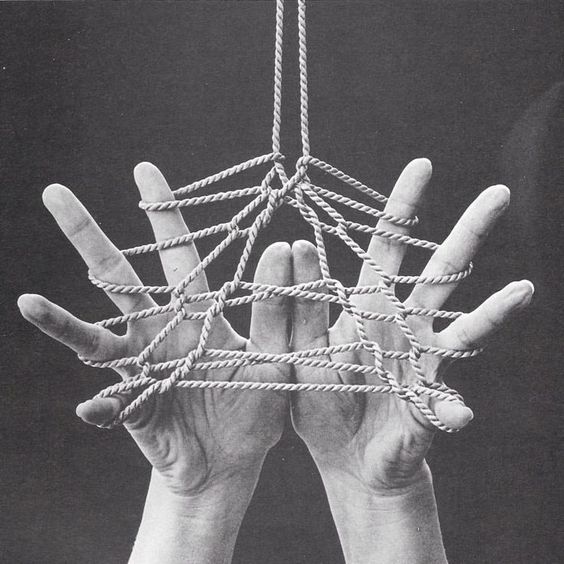

Source: Cat’s Cradles, And Other String Figures. Penguin (1979).

**

My neighborhood is not my community. It’s a nice city neighborhood, with nice old houses and little apartment buildings on tree-lined streets near the university district in Pittsburgh. The residents are middle- to upper-income intelligentsia: literary types and lawyers, professors and techies, a few tycoons. Mostly they’re people who fit my demographics and lifestyle. I am never blasted awake at dawn by somebody starting up a Harley. I get to chat pleasantly about bicycles when a neighbor comments on mine, and we all understand that going to “the theater” means live theater, not the multiplex at a mall. That kind of thing. But intimate friendships and interdependencies are not nearly as common as they were in the past.

Some ties that once ran deeper are gone. There’s no longer a local elementary school; families send their children to assorted public and private schools citywide. Churches and synagogues don’t fill the seats. Few people are lifelong residents — I came here from elsewhere — and certain encounters tell me clearly that this is a place where co-location ≠ community. When a next-door neighbor stopped by to ask a small favor, we spent a few minutes catching up on the past few years: Your daughter graduated already? And moved to Chicago? No wonder I haven’t seen her around …

My actual community is spread near and far, throughout the metro area and beyond. This community consists of people who influence my life, and vice versa. To the extent that life would be diminished without our relationships.

Social scientists study communities like mine, except they call them “networks.” And they’d probably say mine has a typical structure. At the core are people I interact with regularly, right down to the deepest levels of sharing and caring: my wife and our went-to-Chicago kid, some other family members, dear friends, a personal mentor. Fanning out from the core are circles of people I connect with occasionally, and usually for specific purposes: clients for my work, my physicians. As a sociologist might put it, the community is made of both “strong ties” and “weak ties” — with the caveat that “weak” doesn’t mean their influence is weak. Those weak-tie physicians keep my operating systems operating.

My community is an open one. Anybody may enter or leave, which makes it a changing community. New people show up while others drop away. The only membership requirement, on my end, is that I screen out people afflicted with chronic dishonesty. Can’t risk it. (I do, however, let in some folks who are viewed as cantankerous or otherwise difficult. I embrace them for human reasons I can’t fathom, and besides, they can be useful. One person gives advice that’s 100% reliable. Whatever he says I should do, I know to do the opposite.)

Despite its open nature, my community at any given time is a community of choice. The persons in it are those I’ve chosen, and who have chosen me. This also makes it a community of trust. And to me, it’s even more. I cherish the people in my community, inner circle or outer. For example, I know little about our auto mechanic’s life. He’s busy, so I confine my questions to subjects like ball joints. But this mechanic is more than someone who treats us right automotively. I can tell he’s a good man and I’d say I love him for it.

So maybe that’s the mark of a real community. Maybe a real community is built on love.

**

Which reminds me of an incident several years ago, after the 2016 election. A relative of ours is a thoughtful type who tries to avoid rattling the family tree. At a get-together he pulled me aside and asked if it was true what he’d heard, that my wife was upset that Trump had won. I said “That would be an understatement. Why? Did you vote for Trump?” He said “I love Donald Trump.”

**

Many of us wonder how extreme right-wingers and authoritarian regimes have gained the power they wield, in our country and elsewhere. I think that one thing the American right does effectively, much more than progressives or moderates can do, is offering an experience of community. Start with the slogans: “Make America Great Again” is an invitation to be part of a movement. The opposition invokes worthy causes but can’t deliver a unifying message as simple (or, one might say, as simple-minded) as that.

Moreover, a structure exists behind the slogans. Since the 1970s, cadres of conservative think tanks have been founded across the country. The 1987 repeal of the FCC’s Fairness Doctrine opened the door to conservative talk radio. Then the internet enabled new online communication platforms, which have been well colonized by the right.

All this and more adds up to what’s been described as a massive propaganda machine for brainwashing the masses, in order to lay the foundations of latter-day fascism. I share the concerns but don’t quite buy the description. Let’s give individuals more credit than calling them brainwashed. And while the parallels to former fascist regimes look scary, it seems best just to focus on understanding present phenomena.

So here’s another way of looking at it. To me, the right wing machine looks like an ecosystem, a meta-community for incubating communities of shared thought. This ecosystem has apex predators. They’re the big donors who fund the messaging, and the primary perpetrators of it. Some beliefs that they spread are wacky, but the bogus beliefs are secondary. The purpose of the messaging is to promote a shared narrative, a story that frames what’s happening in our time.

And a key thread of the story is: Your community is being taken from you. We must unite to reclaim it. This resonates with many people who feel the loss of a community they once had, or at least imagine they had, or wish they’d had: citizens of old factory towns that have declined since their heydays (as my boyhood hometown has). Suburbanites in de facto gated enclaves who worry about barbarians at the gates, and rural small-towners whose towns are not what they used to be, either.

The messaging comes in various kinds of language and imagery. During the 2022 election cycle, observers noted a lot of GOP campaign ads with “invasion” themes, which warned that outsiders such as immigrants and criminals are invading your turf. In terms of organizing and legislation, there’s been a right-wing emphasis on local control: agitating for parental rights in local school districts, and even running stealth candidates for school boards and other local offices.

In short, what we’ve got is paradoxically strange. A sprawling right-wing community built around the experience of loss of community. A community in which remote means are used — broadcast and online media; the influence of faraway figures like Mr. Trump and high-level organizers — to reinforce people’s idea of a community as being tied to the place where they live.

**

Is the right-wing ecosystem a granfalloon? I decline to answer, on the grounds that I don’t have firsthand knowledge of God’s Will. But perhaps it is possible to shed some new light on a practical question.

What are the fundamental differences that divide us as a nation? Are there personal characteristics, or traits of mind, that make people on the right (especially the extreme right) different from the rest? Much has been written and said on the topic. Nonetheless, I think it’s worth thinking about a further thought. Maybe those of us on either side of the divide have different notions of community and belonging.

I was born and raised in one of a string of towns along the Monongahela River near Pittsburgh. The Mon Valley was at that time a hotbed of American steelmaking and heavy industry, and I have happy memories of my youth in a bustling, blue-collar, Euro-ethnic community. However I became one of the many who left. Moved on to college, then to a rapid-fire series of places around the eastern U.S. (including New York City for a while) … and eventually settled in the Pittsburgh neighborhood I’ve described. A place that is congenial to my habits but not really a “home” in which I feel rooted.

Being more of a networker than a hometowner, I’m more attracted to change and diversity than to tradition and turf. To me it feels natural to live where the neighbors hail from a variety of places: China and Belgium, Manhattan and Minnesota. For me and I’d daresay for many of those neighbors, the defining spirit is one that’s been voiced by the travel-and-culture writer Pico Iyer: “I am not rooted in a place, I think, so much as in certain values and affiliations and friendships that I carry everywhere I go.” And perhaps it’s no coincidence that in this present neighborhood of mine, we vote predominantly blue.

Meanwhile the Mon Valley has become a corridor of towns coping with post-industrial retrenchment. I still visit, sometimes to see family and old pals, sometimes to interview folks for my nonfiction. And among the people who were born in these towns and stayed in them, or returned to their roots in them, there’s been a political shift from blue to red. Although this isn’t true of everyone, voting statistics show the pattern and my “I love Trump” relative puts a face on the numbers.

**

Another place I visit often is a corner of rural Pennsylvania. It’s a favorite spot to go camping and enjoy the great outdoors. It is also hardcore MAGA country. Bicycling through one small town recently — and yep, riding a 20-speed with a helmet on is a pretty reliable way to mark yourself as “He’s not from here” — when I rode through this town, something stood out to me which had blended into the background before.

American flags everywhere. Lines of them affixed to poles along the main street. Flags fluttering on staffs in front of homes and restaurants and second-hand shops, flags tacked to the sides of barns and sheds. You don’t see that back in my ‘hood.

I am on friendly terms with the rural MAGA people. Many are gracious and welcoming; some even seem to make a point of reaching out; I’ve had long talks with them. We know how to dance around subjects that would suck us into contentious political talk. Therefore on the recent trip I didn’t ask “What’s up with the flags?”

But I can hypothesize. My hypothesis is that when love of a place called home is felt, it’s felt with a passion which must be declared — and that it extends to a place called my country. Not necessarily to all the people in it. Rather, it extends to the idea of the homeland, and the idea of belonging to the homeland. Which must be flagged with turf-marks in order to distinguish oneself from, and send a message to, anyone who might be an unreal or less-real American.

Obvious? Maybe. But to quote P.D. Ouspensky — something that only a city intellectual like me would do — there are such things as “obvious absurdities.” Ouspensky (1878-1947) was a world traveler and a mysticist. The latter might lead a skeptical reader to question his views. So I will simply mention that he wrote about seeing obvious absurdities all around him during a particular time period, the nineteen-teens: the time when the First World War broke out. It wouldn’t be the last.

Copyright 2023 Mike Vargo.

Mike Vargo was formerly a journalist for both mainstream and alternative media outlets. He currently works freelance.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Excellent article. And now what do we do?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Keep the faith and vote, I guess.

LikeLike

Yep, you are right. Vote.

LikeLike

Northwest Georgia is my home. Marjorie Taylor Green is our district representative. The head of the local Republican party is the blond, head-cheerleader that I went to high school with, and, yes, she did marry the football quarterback. I think the usual vote is about 85% Republican in this area. I have always, since my first vote in 1968, intuitively, it seems, tended to support Democratic goals and ideology. But, this is my home; my family, the mountains, trees, creeks and lakes are mine and I intend never to leave. Hopefully, someone will scatter my ashes in one of the wilderness areas when I am gone; I think that is against the law, but I’ll pay your fine in advance.

But, I feel no sense of community here; no belonging. People for the most part are friendly and caring, but, maybe not always understanding. I can, to a degree, understand the isolation that others feel.

LikeLike

Thanks, Leo. One reason I left Texas and moved to Pittsburgh 30 years ago was that feeling you describe so well. Lots of nice people in North Dallas, but they had the attitudes of blithe fascists.

LikeLike

Snuck up on me, too. I loved the way Mike teased out the filaments of community, and then shifted gears. Very insightful, helpful, and a real pleasure to read. “Obvious Absurdities” indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the most useful things I’ve read to help me begin to get a handle on what has gotten more more puzzling (incomprehensible actually) in the past few years. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, this essay kind of snuck up on me. I didn’t realize how profound the ideas are until I was almost finished reading it

>

LikeLiked by 2 people