Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

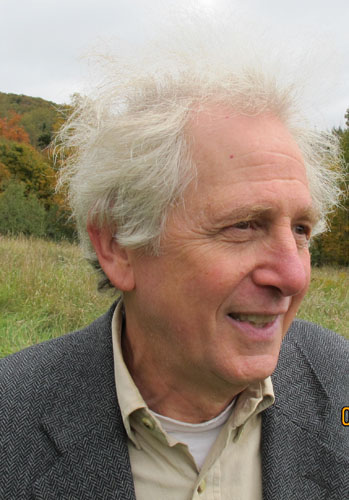

Baron Wormser: Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Epitaph”

In the 1934 volume of poems entitled Wine from These Grapes, Edna St. Vincent Millay included a sonnet sequence with the forbidding title “Epitaph for the Race of Man.” To be sure, 1934 was a bad year for humankind, but Millay took a very long view in her poem, including dinosaurs, geology, and astronomy, “fifty million years of jostling time,” as she put it. Her overview remains breathtaking. She was one to claim the high ground for poetry (no scuffling with the plain-spoken or commonplace for her), but typically the ground she favored spoke to the many shades of passion, from love-stupor to disillusion and weary dismissal. In the “Epitaph” sonnets Millay used her eloquence for a different purpose—man’s end.

By tradition, poets have the authority to write epitaphs. It goes with their famous license, their claiming the verbal right to confront death in whatever context death presents itself while using poetry’s concision to arrive at a just, incisive summary. Epitaph differs from elegy in the bluntness of its defining mission; the inscription on the tombstone is palpable—this and no more. An epitaph summons up a feeling of utter finality. The reader hears the echo of “futility” in that “finality.” Millay certainly had that on her mind. “To what end?” was literally her task.

In the first sonnet in the series she wrote, “Earth will have come upon a stiller day / Man and his engines no longer here.” Out of the accoutrements she might append to “Man,” she chose the mechanical, the industrial. Her sonnets speak movingly to human attainments–“Man with his singular laughter, his droll tears / His engines and his conscience and his art”–but Man is “industrious.” The “engines,” those metal avatars of modern times, cannot be pushed aside, however much a poet may have wanted to. As for Man’s flaws, another sequence of sonnets might be devoted to them. Millay was content to note “Mania” and “Obsequious Greed.” She saw “Man” as “stealthily betrayed / Bearing the bad cell in him from the start / . . . That wild disorder never to be stayed.” Millay was brilliant at summoning the wages of disorder in one line: “Till Reason joggles in the headsman’s cart.” For those unfamiliar with the word, a “headsman” is a “public executioner who beheads condemned prisoners.”

Hamlet’s rhapsodic declamation would not have been far from Millay’s mind: “What a piece of work is a man!” Nor would his counter-remark have been far: “And yet to me what is this quintessence of dust?” In her sonnets, Millay was willing to test Hamlet’s question. Her stance deserves consideration for we are in a realm that has nothing to do with self-expression, with art for art’s sake, or for the conceits of a self-regarding Zeitgeist, which is to say the modernism that relegated Millay to the back of the artistic bus, her means and her outlook both judged old-fashioned and, hence, irrelevant. We are in a realm where the poet consciously cultivates timelessness. The long-standing meter, the sonnet form, and the sometimes ancient vocabulary, all these tools that Millay cherished do not speak to a willful avoidance but, on the contrary, to a commitment to use the fullest means she could lay hands on.

Eloquence is directly related to stature. False eloquence, the straining for effect, whether grandiloquent, conniving, or sentimental, cannot make up for the failings of a narrow, often grasping intention. Genuine eloquence is, understandably, hard to come by—ideally the situation and the language both attest to something substantial, something out of the grocery-list, how-are-you-doing ordinary. Eloquent language is memorable language. There must be something worth remembering, something truly compelling. The stature of capitalized Man and Man’s fate offered Millay a scope she hungered for. What good were the honed tools and rich yet pithy language if they could not tackle the largest matters?

The retreat from eloquence that modern times manifested made sense. So much language was palpably false, shot through with lies, flattery, ideology, and deception. So little was truly stirring and what was stirring was so dark as to require an anti-eloquence, a hard-edged modesty, and a feeling for immutable, discordant metaphor—Celan’s “the black milk of death” being a famous example. If you no longer have any faith in human beings, it’s hard to be eloquent. And, equally to the point, why would you care? All this darkness was very much brewing in 1934 and, indeed, had been set in catastrophic motion by World War One. The impassioned speeches about this or that homeland and its supposedly unique virtues sounded very feeble beside the millions of deaths. What unavoidable necessity claimed those deaths? Eloquence had no answer.

The caring that Millay invested in her sonnets was a poet’s cardinal caring for the integrity of language. This meant a considerable range of words and tones, the strategic use of the “poetic” as opposed to the plain-spoken, and the striving for sustained language that matched the enormity of the human enterprise on earth and its demise. In her way, she was after something not very different from John Milton in Paradise Lost, though she would have laughed, I suspect, at the comparison. Certainly, she would not have protested as to what was at stake in her chosen subject matter—the outcome of human life on earth. She was willing to face the simple truth that Man’s greatest problem was Man. In sonnet XV, she wrote, “You shall achieve destruction where you stand, / In intimate conflict, at your brother’s hand.” In another sonnet, one that uses the analogy of splitting a diamond (“One and invulnerable as it began”), she wrote that Man was “split along the vein by his own kind.” In the diamond sonnet (XVII) Man winds up “set in brass on the swart thumb of Doom.”

The lines I have quoted give the flavor and tenor of Millay’s poetic endeavor. She wasn’t afraid to bring in the largest mythic entities, as is the case with “Doom.” She wanted that deep, remorseless, stark perspective. She also wanted the language that conjured up the tradition behind her words, the firm metaphorical ground upon which she stood and wrote. Yet, at the same time, a sadly wry quality is felt. How wretched that “achieve” is in “achieve destruction.” It is, however, the perfect word for human doings, that “Look, everyone, at what we’ve done. Betcha can’t wait to do it or use it or lose it or abuse it.”

What makes this all the more disturbing is that Millay showed how resilient Man is. He endures volcanic eruptions, floods, and earthquakes, to note three natural disasters she wrote about. The cities are shattered and he rebuilds them. The fields are flooded but when the waters recede, he plants again, “his pocket full of seeds.” Indeed, disasters bring people together and help them to appreciate one another. “He saw as in a not unhappy dream / The kindly heads against the horrid sky, / And scowled, and cleared his throat and spat, and wept.” That monosyllabic last line lays bare Millay’s feeling for dramatic speech. She was alive to the passion of complexity and the complexity of passion; after all, so many of her love poems came from that vexed place. Thus she gave us the show Man makes, his recognizing camaraderie while needing to assert his dissatisfaction with the human lot while finally breaking down in tears. Her poems are full of these bravura moves: so much can happen in a few pentameter lines. One can see why the ostensibly chopped-up measures of free verse held little charm for her.

It is easy to dismiss Millay as an anachronism, someone who believed too much in her traditional stance, someone who liked to pose in Shakespearean weeds, who reveled in the flinging-an-arm-out gestures that such language afforded her. Are her lines hollow? Is it all a pose? Does the very fluency of meter undermine her argument about the disheveled nature of Man, his inability to add up to much of anything, that falling down and getting up and falling down again that Samuel Beckett had such a nose for? Beckett and Millay? Am I stretching it? I don’t, in honesty, think so. Beckett and Millay both were appalled by human behavior. I think that’s a fairly rare quality for so-called creative writers who tend to be so busy with the task at hand that most nasty scents evaporate in the hurly-burly of pounding the keyboard. Both had a comic eye. Millay relished a pratfall but, like Beckett, was willing to see Man as a pratfall writ large. Or small, as Beckett would have it. In that regard, they differ, for Millay was stubbornly humanist. Beckett’s honing of language until it reached nothingness was foreign to Millay who relished the human capacity for aptly heightened language.

A significant contemporary confusion lodges in the belief that heightened language gets in the way of being clear-sighted. Millay shows that isn’t true. Here are the final four lines of Sonnet XIII: “Earthward the trouble lies, where strikes his light / At dawn industrious Man, and unamazed / Goes forth to plough flinging a ribald stone / At all endeavor alien to his own.” The old meaning of “ribald” is in play here, that which is “low, coarse, or scurrilous, especially blasphemous.” Not many poets would come up with that adjective for “stone,” but that choice indicates Millay’s tenacity, imagination, and sheer scope. We can say that finally we are left with words, whether written or spoken, and that Man will go on his unavailing, fatally flawed way. True enough or at least true until Man, among other things, takes poetry seriously. Millay certainly did her part. That a poem of the caliber of “Epitaph for the Race of Man” is largely ignored is one more in an endless number of scandals that testify to a society indifferent to the lifelines art has thrown to it. We remain, to quote Millay at the very end of her poem, a “poor, scattered mouth.” Beckett could not have said it better.

copyright 2023 Baron Wormser

In 2000, Baron Wormser was appointed Poet Laureate of Maine by Governor Angus King. He served in that capacity for six years and visited many libraries and schools to talk about books and writing.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

5 comments on “Baron Wormser: Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Epitaph””

Leave a reply to Vox Populi Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on August 6, 2023 by Vox Populi in Literary Criticism and Reviews, Opinion Leaders, Social Justice, spirituality, War and Peace and tagged Baron Wormser, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Epitaph”, Epitaph, Epitaph for the Race of Man, Hamlet, sonnet.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-lhmSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,950,341

“We can say that finally we are left with words, whether written or spoken, and that Man will go on his unavailing, fatally flawed way. True enough or at least true until Man, among other things, takes poetry seriously. Millay certainly did her part.” Yes, she did! 💖

LikeLike

Very good appraisal of Millay–and, as Thom Gunn has written, poetry has a long history of honoring the archaic, so-called “outworn” devices of diction. Too many of today’s poets prize the ironic sneer, as if devaluing our ancient right to our sincerity. Millay’s brand of “archaic” sincerity is everlasting.

LikeLike

Thanks, Tom.

>

LikeLike

I have to dive into Edna St. Vincen Millay again. I always loved her work, but this piece really whetted my appetite.

LikeLike

Oh, yes. Millay is the best.

>

LikeLike