Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Baron Wormser: On Moral Grounds

by Richard Michelson

Slant Books, 2023

However much modern society tries to push away the specter of suffering via nonstop entertainments, trumpeting of technological progress, news (often sensationalist), blatant materialism, and seemingly irresistible electronic gadgets, that effort must, given the mortal nature of the human condition, fail. Each of our lives can be measured by the extent of that failure, though, for some of us, it seems no failure at all. We push away suffering, to say nothing of death and grief as far out of the picture as we are able. We are always getting on and going places and achieving “closure” along the way. Suffering spoils the party. For others, however, it is not so easy. Many a dire misfortune falls on our by-standing heads from seemingly nowhere. I mean murders, suicides, overdoses, crib deaths, and fatal crashes, to name five harrowing instances. You hear about them, if not every day then many days. What they may portend to those who are intimately involved is another matter, one that, with a shudder, the bystander may gratefully consign to oblivion.

It was not always so, as the tales of Oedipus and Job remind us. Suffering was the permanent ground humankind stood on, as represented by infant mortality, women dying in childbirth, constant war, and ravaging plagues. What to make of such suffering was an understandable human preoccupation. One path led to tragedy, the irreversible force of fate, also known as doom. One path led to wrestling with the All-Mighty and raising one of the most perennial questions—“Why me?” The former path led to a sense of how terribly fraught life was and how unknowable—a riddle inside a mystery. The latter led to a sort of empowerment in the sense that the individual, however abased by the divine power, could argue his or her case. Some feeling of mutual recognition glimmered in the darkness. All was not lost, even though, at times, all might seem very lost. The texts I have cited are ancient but modern times, filled to the vicious brim with genocide, have given the old crises new contexts.

In the Jewish tradition, individuals must sort out their arguments on an individual basis. There is, to be sure, an occasion of group repentance, a sanctioned, holy day of atonement, but the individual’s moral sense may well remain confused, outraged, and a host of other possibilities in face of the visitations of suffering. Christ, as a messiah, offered atonement based on his ultimate suffering and his triumph over death, but the Jewish sense of life stayed with Job, with the bafflement and the blessing that ancient faith could give. Again, given the ordeals of modern times, that sense of life has been sorely tried, to which a rich literature attests. The sheer fact remains that, often, a person’s suffering, since it is both personal and historical, seems to have no end. Only the individual can make that end. We think of Paul Celan’s death and countless others.

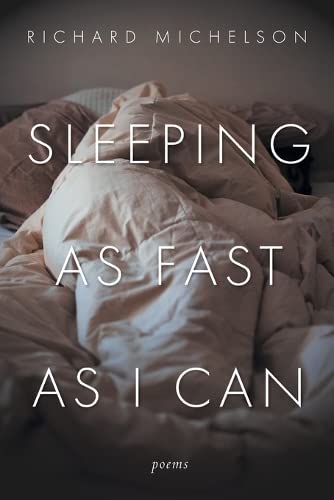

All this brings me to Richard Michelson’s latest book of poetry, Sleeping As Fast As I Can (the title comes from a Yiddish folk saying Michelson references as an epigraph). Michelson has been a devoted practitioner of the art of poetry for decades as well as a celebrated author of books for children. He knows what he is doing as a poet and the range of forms he employs in Sleeping As Fast As I Can shows that. Yet the power of the book comes from the classic situation of Oedipus and Job—not knowing what he is doing, facing the elemental forces of suffering and being humbled by them. One can be humbled into silence and one can be humbled into words. Or one can feel both—the silence that underlies the words. It is this last state that Michelson touches on in many of his poems, that feeling one has when one comes to the end of a carefully wrought poem, a mingling of satisfaction and blankness, a gathering and a letting go, something so bittersweet it defies all definitions.

Michelson’s father, who owned a hardware store in Brooklyn was to quote from his remarkable poem “Life Sentence,” (from the first of the three so titled in the book) “gunned down, she [the poet’s mother] repeats, for ten dollars and half a tuna sandwich.” There is the given—as bald as possible yet containing numerous dimensions of torment, a state we are loath to acknowledge in our therapeutic times yet a state both Job and Oedipus, in their different ways, were familiar with. The fact of his father’s murder cannot be undone. All the words in the world, as Michelson the poet too well knows, cannot undo a death. What then? Where then? How then?

Here is “Life Sentence” in its entirety:

A life sentence is what was handed down to the thief

that gunned down your father, my mother said,

her breathing labored, as if by hammering words—tread

and riser—into a flight of stairs, she could climb past grief,

ascending up and out of her own history. Gunned down,

she repeats, for ten dollars and half a tuna sandwich.

The briefcase, an open disappointment, tossed in a ditch

and found, infested with fingerprints, each a proper noun

announcing, like an intricately hand-lettered calling card,

the murderer’s name and table number. To set the scene

for her story, my mother drops metaphor—at seventeen

I married the boy next door—as we exit the graveyard,

down three steps, stumbling on the bottom one, broken

and forgotten, like a life unwritten, its sentences unspoken.

A sonnet. So the poet goes to a hallowed form in search of a steadying hand and the form with its measures and rhymes responds to the poet’s deft touch. All is terribly in order, as a small drama occurs in a small space. We have the lexical ambiguity of “life sentence” cutting in several directions: that which is defined, that which cannot be defined, that which is grammar, that which is time. We have two nameless characters who exist in their relationship to one another—mother and son. We have very careful attention paid to those little expressive details—the steps, the stumbling—that hold enormous feelings. We have the negative definition that death brings us to—the “unwritten” and “unspoken.” And we have the finality of a poem ending, a little thing trying to encompass something so much larger.

A murder can occasion all manner of responses from those who are directly affected but one that seems eternal is simple grief. The poem, in its avowal of form and the articulate energy that is poetry, gives voice to that grief. For the poet that task is really a duty, one that for Michelson involves the Jewish religion he was born into and that is part of who he is. One of the distinguishing traits of that religion is its moral tenacity, its ability to ponder the byways of human failure and misgiving. Anyone can salute success, bur it is our failures that teach us who we are and how much those failures imbue every facet of every day. A murder is a deep failure, the wanton taking of a life that shoves the misery of the human predicament in our faces. We have a thousand reasons and excuses about neighborhoods, guns, poverty, race, desperation, drugs, and they are all true. And they are all irrelevant before the terror of our fragility, the life so easily severed. Thus the question that Michelson asks over and over in his book, a book of prayers, meditations, riddles, and elegies, is—What is this? He is reduced to awe and wonder when beholding the spectacles of misunderstanding and violence that ruin so many days and that have figured so heavily in Jewish history. He is like a child but he very much is not a child.

This reduction is a blessing, even though he must live with the impenetrable silence brought about by his father’s death. The poet wrestles with meaning, much as Jacob wrestled with the angel. With whom Jacob wrestled has been contested, but the act of wrestling, the struggle, has not been contested. The outcome of the poet’s wrestling has nothing to do with victory—every darkly Jewish joke could attest to that—but with perseverance and honesty, the willingness to take on the circumstances—tuna sandwiches, murders, broken steps, marriages—in all their impossible heart and heartlessness. This is, to repeat, a moral endeavor in the sense of looking steadily at what can so easily be dismissed out-of-hand as hopeless and pointless. Politicians do it every day in favor of rhetoric and much worse than rhetoric.

Inevitably a book such as Michelson’s, and I have only focused on one poem in a book replete with poems that draw the reader to them again and again in their depth of feeling and language, brings up the place of poetry in contemporary American society. In one sense, that place—or lack of place—doesn’t matter. Where Michelson is writing from is a very old place that has outlasted numerous so-called civilizations. Moral ground is like that. In another sense, it does matter, or rather it could matter, if places existed in the society to recognize poetry as a crucial human endeavor. Obviously, schools do not fit this definition since they have many ulterior motives that have nothing to do with the moral searching to be found in a book such as Michelson’s and, for that matter, in many other books of poetry by poets from many different backgrounds. The society prefers to be objective or whatever it tells itself while it lurches from one gaping wound to another. We not only refuse to take the hand that poetry extends to us but act as though there is no such hand. Michelson has extended that hand in this book. Any of us, who, as the expression goes—“has the language”—can take it.

Copyright 2023 Baron Wormser

In 2000, Baron Wormser was appointed Poet Laureate of Maine by Governor Angus King. He served in that capacity for six years and visited many libraries and schools to talk about books and writing.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

6 comments on “Baron Wormser: On Moral Grounds”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on June 25, 2023 by Vox Populi in Literary Criticism and Reviews, Opinion Leaders, Poetry, Social Justice, spirituality and tagged acceptance, Baron Wormser, death, elegies, fathers and sons, Job, morality, Oedipus, On Moral Grounds, Richard Michelson, Sleeping as Fast as I Can, suffering, violence.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-liCSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,952,481

Such a thoughtful essay, Mr Wormser. I appreciate how you have situated your sympathetic and helpful review of Michelson’s book on the whole vast extent of “moral ground.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Baron. Your powerful, heartfelt review led me to order Michelson’s book. “Moral ground is like that.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

“One can be humbled into silence and one can be humbled into words. Or one can feel both—the silence that underlies the words.”

I want to read that book.

LikeLike

Excellent essay and yet another poet I need to read (which is a good thing). But on the subject, John Lennon has a song (I Found Out) that addresses this very issue:

I seen through junkies, I been through it all

I seen religion from Jesus to Paul

Don’t let them fool you with dope and cocaine

No one can harm you, feel your own pain

On the original lyrics that came with the album, however, the last line reads: “It don’t do you no harm, to feel your own pain,” or something similar (I’m pulling this from memory) Of course, he doesn’t sing that, and I figured it just didn’t sound right and he changed it at the last minute. Moreover, despite the fact that I played this album incessantly as a teenager and beyond and know the lyrics to every song by heart, I didn’t listen.

LikeLike

Ah, if only we knew then what we know now.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person