Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

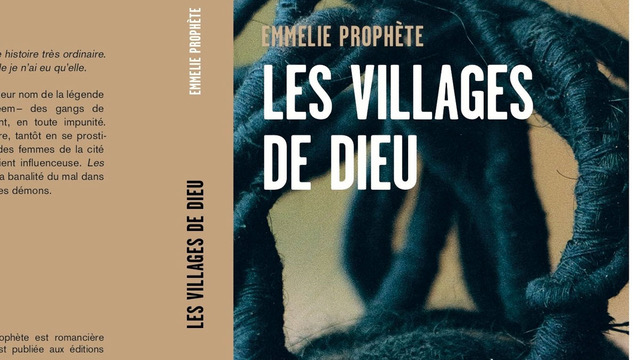

Emmelie Prophète: The Villages of God (excerpt)

I was not afraid. I’d grown used to the sound of guns. I grew up in this Cité where there’s never been a truce, where death does the rounds at noon just like at midnight. It’s been nine months now since Grandma died from fear. It was a Sunday afternoon that had started out calm until the rumour went around that a few guys in Makenson’s gang had whistled after the girlfriend of a member of Freddy’s gang as she was walking home from church. The two gangs that laid down the law in the Cité were not shy about provoking one another, but there had never been, until that Sunday afternoon, a direct confrontation. I will never forget my grandmother’s protruding eyes, her hands squeezing my wrist.

“Grandma, you’re hurting me!” I cried.

“Cécé, Célia, my child, my little one,” she rattled. “Cécé, I feel as if my heart is going to explode. I am going to die.”

I slept in the same bed as Grandma. Always had. I knew right away she was dead. She had become stiff. Cold. I couldn’t, as I always had, put my right leg over her to help fall asleep. I started talking to her, and don’t remember what I said, except for some prayers she had taught me. I could not hear the sound of my voice. Rapid gunfire rang around me, and the racket continued until dawn.

I went to wake up Uncle Frédo. The noise I made opening the wooden door and almost breaking the latch did not disturb him. He was totally drunk, as usual. I was not able to rouse him and went to knock at my neighbour Soline’s house. She agreed to go with me, nudging me along to make me go faster. To her I was nothing but a little liar. How could I pretend that Grandma had died when only yesterday they had been at mass together and she was doing perfectly fine then!

Soline paused at the doorstep, her big breasts floating in her floral nightdress. Like everyone in the Cité she had not slept. She had dark rings under her eyes. She stepped right over the four-inch threshold that Grandma had had put in, between the little porch and the front bedroom entrance, so that the rainwaters would not enter the house.

“She really is dead,” I managed to stammer, as we entered the room.

“Be quiet, petite,” she replied, her eyes opening wide.

“Christa! Christa!” she called out, feeling Grandma’s brow and neck before letting out a scream.

Tears ran down her round cheeks. I too started to cry, then launched into the keening you hear when someone in the Citédies. Neighbour Soline placed her thick, coarse hand over my mouth.

“Petite,” she whispered. “You’re going to wake up Freddy and his men. They’re sleeping. They just put themselves to bed. You should understand these things at your age ”

I lowered my head while Soline, her two hands on her head, went into a little foot dance and chanted, “Bon Dieu ô! Bon Dieu ô!”

Uncle Frédo, almost as dead to the world as his mother, snored in his little room whose door I’d forgotten to shut. There was no furniture in there but a small iron bed and an old fuchsia-colored suitcase containing the few clothes he owned.

Great calm had returned to the Cité. Freddy’s gang had beaten Mackenson’s. Thirtyish deaths reported. Complete capitulation. Summary execution for the stubborn who would not lay down their weapons. One gang only, one base, as they called it, would henceforth be calling the shots in the Cité of Divine Power, Freddy’s.

My neighbour Fany had called the funeral service. It arrived two hours later, a small truck like the ones that carried people between Boulevard Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Martissant. It had “Divine Grace” written on its brow. Neighbour Soline had put on a man’s green apple-coloured shirt over her floral nightdress, and had pulled on a pair of long pants. She looked odd under all these layers, and I couldn’t help but think of the crazies and characters who strolled the neighbourhoods during Carnival, which we called Mayotte, people I was afraid of when I was little.

As usual, Soline had all the say, and grief conferred on her an even greater authority. She commanded that we wait till 3 o’clock before starting to mourn. Joe, Edner, Fany, Fénélon and his wife Yvrose made no objection. Rigor mortis had set in and made it impossible to close Grandma’s eyes.

“In two or three days that will be possible,” said the funeral service worker as he transferred Grandma from the bed to the stretcher with the help of his assistant and with the dexterity of one who spends a lot of time with dead bodies.

Uncle Frédo woke up. He looked old for his thirty-eight years. He had slept in his clothes, now all disheveled, and he smelled of booze. When they covered Grandma’s head with the white sheet, he started screaming hoarsely, “Maman! Maman! Maman!” and Soline, Edner, Joe, Fany, Fénélon and Yvrose, all at the same time, told him to shut it.

“Be quiet! Quit the thoughtless drunk talk or you’ll wake up the gangsters.”

Uncle Frédo threw himself on the ground and started to moan softly.

It was Grandma herself who had built this house. She loved to talk about it when given half a chance. In the evening if she heard an odd sound on the roof, often just bored kids throwing stones, she would sit up in the bed and address the affront in a clarion voice.

“I built this house all by myself, I have no debt,” she announced. “I buy nothing on credit. I need peace and quiet.”

Her monologue could go on for several minutes, and she made sure all the neighbours heard her, Soline to her right, Fénélon and Yvrose to her left, Nestor out back, Pastor Victor and his wife Andrise a bit further on, Fany and her sister Élise in the house across the way, and whosoever was passing, whoever might envy or begrudge her.

She would often relate to me how, when she had bought the plot forty years earlier, hardly anyone ever went through there. It was nothing but bushes, and her closest neighbours lived nearly five hundred metres away, a man called Joachim, his wife, and their daughter. All three of them were so old you could scarcely believe she was their daughter. Grandma was never sure if the seller had been the true owner. No survey had been done. Helped by my mother’s father, she built these two rooms, and moved in. More people arrived after that, at a frenetic pace, and put up make-shift shacks, leaving only alleyways to get about. The state never protested, never bothered to get involved.

There was no stopping Grandma’s account. My mother, Rosia, was born in the big room with the help of a midwife. Her father had already left the house.

“With a stuck-up tramp of a girl. Nothing to her name but four children already running around her.”

As the years passed her anger did not let up.

Of my mother there are two likenesses. One is a small yellowed ID photo taken when she was six years old so she could go to school. She is looking into the emptiness, probably feeling shy in front of the photographer. She looks sad in it. In another, she is standing to the right of Grandma, seated in a huge chair, with Uncle Frédo to the left. No one is smiling. They are all rigid. The background features a waterfall. Water, grass, rocks, a landscape that had everything to be enchanting but just wasn’t. My mother, Rosia, wears a pink dress, long with straps, with ruffled flounces below, level with the top of her white stockings. Her shoes are black. Grandma is dressed in a white outfit and heeled sandals. She has a small purse on her lap. The purse is in the dresser still. Uncle Frédo sports a white suit and a small red bow-tie around his neck. His shoes are well-polished. He stands erect and straight. He is four and Rosia eight. I look a lot like my mother. When I was little, I stood up to Grandma and said that it was me. That made her laugh. A sad laugh.

My mother died at the age of twenty. I was two and have no memory of her. Not even a scent. Nothing.

“I think she caught that dirty disease,” whispered Grandma, meaning AIDS.

Pastor Victor and his wife Andrise came to explain to her that evil forces had killed her daughter and were killing lots of young people like her in the city. But Grandma was no fool. The young doctor she had met at the General Hospital — very clean, honest-looking, so nice she prayed to God right there that Frédo would become like him — he said it was AIDS.

Rosia was already in pretty bad shape when her mother brought her to the hospital. For several weeks she had wasted worrisomely away. The young doctor asked her only affirmative questions, already sure of his diagnosis.

“You have lost a lot of weight; have you trouble swallowing?”

“Do you have prolonged diarrhea, vomiting?”

“You have lesions on your skin; have you been coughing?”

He was handsome and impassible. He recommended tests, just to be sure, and that the girl, given the state she was in, be hospitalised. Grandma had no money. The public hospital was on strike. The young doctor sent Grandma to one of his colleagues at the Health Center in Portail Léogâne who gave her some serums for free, medicine that would help Rosia feel better. She died a month later.

Grandma said she regretted not beating her, not keeping her away from the hoodlums who had lured her, after a difficult period, to drop out of school at fifteen. She could have been like that young doctor who had given them the medicine. She could have gone on to university. But she had taken to drink and taking drugs, and had gotten herself pregnant at eighteen with no idea who the father was.

“Anything can happen when you are high all the time,” said Grandma.

After the scoldings, and the slappings, Rosia would spend days away from home.

“You, I did everything to protect you, I did,” Grandmother would whisper, passing her hand through my hair. “I kept you close to me always, even if it made you a mother’s pet. You will sleep against my back until you are adult and settled. I will trust no one with you. I’ve already paid dearly for your mother.”

Translation copyright 2022 by Aidan Rooney who is indebted to his French IV-H class at Thayer Academy for finessing this translation.

From Emmelie Prophète’s Les Villages de Dieu (Mémoire d’Encrier, Montréal, Nov. 2020).

Set in Port-au-Prince’s shanty towns where gangs pillage, rape and murder with impunity as they vie for influence, The Villages of God is the survival story of Cécé, the novel’s orphaned teenage narrator. Written in crisp and crystal prose, alternating stretches of memory and chronicle carry Cécé through her days as she becomes, thanks to her cell-phone, a young woman of influence. It is a story of resilience and fragility, of life and death up close, of hard times made vivid and banale.

Since it came out, the novel has received considerable acclaim in the francophone world, winning the 2021 Prix FetKann Maryse Condé. Last May, Emmelie joined Aidan Rooney and others for Translating Haiti at the Massachusetts Poetry Festival. In January 2022, Emmelie’s 2007 award-winning novel, Les Testaments de Solitude, came out in translation as Blue. Also in January, Ariel Henry, the Prime Minister of Haiti, introduced Emmelie as Haiti’s new Minister for Culture and Communications. Finally, high-schoolers in Guadeloupe, Martinique and Guyana have just voted Les Villages de Dieu worthy of the Prix Carbet for best new novel from a contemporary Caribbean writer.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for sharing. What a world, and it is going on now, here, just south of our country.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Too true, Kim. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Powerful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Barbara. EP is a powerful writer.

LikeLiked by 2 people