Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

George Yancy: Black Men Endured Sexual Exploitation Under Slavery. Their Story Is Rarely Told.

~

Historian Thomas A. Foster discusses his new book Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men.

Black knowledge production, Black self-understanding, and the power of Black people to represent ourselves is under attack, which means that Black identity and Black meaning-making practices are being erased. In The Mis-Education of the Negro, published in 1933, Black historian Carter G. Woodson wrote, “The education of the Negroes, then, the most important thing in the uplift of the Negroes, is almost entirely in the hands of those who have enslaved them and now segregate them.” Woodson is pointing to the assault on Black dignity and Black agency.

Almost 100 years since the publication of Woodson’s indispensable text, the Trump administration has attacked the reality of Black existential dread and pain experienced in this country. In short, the president is attempting to whitewash U.S. history. Just think here of the removal of the Black Lives Matter Plaza and ground mural and the removal of Black history from museums, parks, and monuments. Think specifically of Donald Trump’s attack on the Smithsonian Institution, which he charges with focusing too much on “how horrible our Country is, how bad slavery was.” In his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass described the horrible beating of his Aunt Hester as the “blood stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery.” Trump would have us believe that there is something “positive” about the hell of slavery.

As Francine Prose writes, “The point is to create a national identity that mirrors the president’s own view of himself as a model of moral purity, an angelic being who has never made a mistake that merits an apology or even a moment of regret.” The fact of the matter is that Trump’s view of himself is a lie, a case of deep and destructive self-deception.

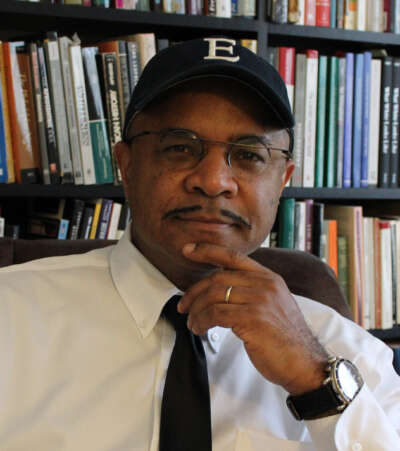

Considering this systematic attempt to erase Black history and the history of Black pain and horror, I conducted this exclusive interview with Thomas A. Foster, a historian of early American gender and sexuality who is associate dean for faculty affairs and professor of history at Howard University, as well as the author or editor of seven books, including most recently, Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men. It is from this book that I approached Foster to discuss the overlooked, understudied, and undertheorized fact that Black men under slavery were sexually assaulted/raped. This reality speaks to just how bad slavery was, how pervasively sexually violent it was toward both enslaved Black women and men. It is a history that we must tell, and damned if Trump will control our narrative about our pain and our joy.

~~~

George Yancy: Just last semester in the fall, I taught a course where I had my students read Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. There is a very revealing description that Douglass provides regarding the white slave breaker, Covey. He is described as a poor white man, but he was able to purchase a Black woman, Caroline. Covey was excited to buy her specifically for the purpose of making her a “breeder,” which means that he had to hire an enslaved Black man to have sex with her. As a result of this forced union, Caroline had twins. Douglass says, “The children were regarded as being quite an addition to his wealth.” I pointed out to my students how Black bodies were exploited to produce more “chattel.” It is clear to me that Caroline was the victim of slavery’s dehumanizing practices, and that any sense of her sexual autonomy was deemed inconsequential. What is not necessarily clear is how the Black enslaved male was also stripped of his sexual autonomy. Both were clearly sexually assaulted by a white supremacist institution.

This made me think about the paucity of work dealing with the sexual assault of enslaved Black men. In your significant historical text, Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men, you precisely and critically write about Rufus, an enslaved Black man who was forced to have sex with an enslaved Black woman, Rose Williams. In short, your work helps us to explore those cases where Black males were sexually assaulted during slavery. Given the paucity of work in this area, your work is so important and revealing. You recognize this paucity when you write, “But the academy has been slow to produce studies that verify oral traditions that include sexual violence against enslaved men.” Why do you think the academy has been slow in this regard?

Thomas A. Foster: First, thank you for this opportunity to discuss Rethinking Rufus and for your interest in the book. As we know, historians study the past on its own terms, but the questions we ask about history are always informed by the present. We traditionally work from written sources, have an uneasy relationship with oral traditions and family lore, and the loudest voices in written sources tend to shape which topics are studied first.

At the same time, our country is still working through the legacy of enslavement, and both in source material and in cultural awareness, sexual assault of men remains a poorly understood topic. The rape of men by other men is still frequently treated as a source of derisive humor. The rape of men by women is also deeply fraught. Consider how the legal system and the court of public opinion often view relationship violence perpetrated by women against men, or sexual intimacy between adult women and adolescent boys.

This is not to say that our culture has a firm grip on sexual violence against women. We can see this clearly in the ongoing horrors revealed in the Epstein files and in the hypocrisy that shapes how the legal system and society respond to the sexual assault of Black women. Discourse about rape has deep legal and cultural roots in this country, and yet even today, with all of that awareness, rates of sexual assault remain high, and women and girls must fight for justice despite a legal and cultural apparatus that has existed for generations.

Given all of this, it is not entirely surprising that sexual assault of enslaved Black men has failed to garner sustained scholarly attention. The sexual assault of white men and boys in colonial America and in U.S. history is also understudied.

Gender roles have long defined sexual assault in ways that obscure an understanding of sexual violations of men. There were no legal protections against the rape of enslaved Black women or enslaved Black men. In both the legal system and the broader culture of colonial America and the early United States, sexual assault was most often framed through the racial and gender ideology of white womanhood, the ability of white men to protect their dependents, and the imagined criminality of perpetrators who were non-white and non-elite.

As a result, sexual assaults committed by white men have also gone largely understudied, especially when scholars rely primarily on legal sources that rarely brought those men to justice. The imbalance in the sources has shaped our historical understandings, and that problem has only been compounded by cultural discomfort — especially when the gender, race, or class of the actors don’t fit familiar scripts.

You argue that abolitionist literature would have intentionally avoided the issue of sexual violence against Black men. Say more about this. Was it fear? What was the white ideology driving such an avoidance narrative?

Abolitionists were trying to persuade an audience about the atrocities of slavery and that enslavement was morally repugnant, and they often framed their arguments around concerns that resonated with white northern readers: the sanctity of the family, violations of gender roles such as the male “protector” and the “virtuous” woman, and their political opposition to the South.

In that context, the sexual assault of enslaved Black men was not a particularly effective rhetorical strategy. There was only a very little conceptual framework through which such violence could be understood — no supportive biblical language, no legal recognition, and no widely shared way to imagine men as sexual victims. I don’t know that abolitionists were consciously afraid to address the issue so much as that it was not deemed a topic that would resonate with their intended audience.

More broadly, I would speculate that the sexual assault of men was threatening to patriarchal systems because it holds the potential to expose male vulnerability and destabilize gender hierarchies.

In your book, you cover the important historical work that shows just how brutal slavery was in terms of its economic and libidinal investment in the rape of Black enslaved women. From the example given by Douglass, and what happened to Rufus, however, both Black bodies were subjected to the “breeding” process, and hence both were victims. Elaborate on the process of forcing Black men to be “breeders.” Talk about how this is a manifestation of sexual assault.

Black men and women were expected to produce children because of the financial incentives created by a system that defined the children of enslaved Black women as born into lifelong bondage and as the legal property of the person who enslaved the woman.

Scholarly attention has rightly focused on the forced reproduction of enslaved Black women, but that focus need not come at the expense of understanding the position of enslaved Black men, who were also denied sexual autonomy, including the ability to choose with whom they would have children. When reproduction is compelled under threat of violence, sale, or punishment, it is a manifestation of sexual assault, even when it is not named as such in the sources.

To begin to take seriously the claim that enslaved Black men were sexually assaulted on plantations, one must confront white supremacist assumptions and myths regarding the so-called “hypersexual Black male.” In your book you write, “In the era of slavery, Anglo-American culture already embraced a message about Black men as particularly sexual, prone to sensual indulgence, and desiring white women.” How does one cut through these myths to even begin to accept the view that Black men can be victims of sexual assault — victims of white male patriarchal oppression?

One place to begin is by listening carefully to the voices of formerly enslaved Black men, as happens in Rethinking Rufus in a chapter that examines the importance of autonomy for enslaved and free Black men within family life and intimate relationships. The WPA Slave Narrative collection and other sources offer glimpses of how Black men resisted, adapted, and attempted to assert control over their intimate lives under extreme constraint.

Formerly enslaved Black women also sometimes wrote about violations they witnessed. As scholars have noted, Harriet Jacobs’s autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, contains an account that strongly suggests the sexual violation of an enslaved Black man by a white man. Jacobs never names the assault explicitly, but her coded language — typical of 19th-century moral discourse — points clearly in that direction. She describes Luke as being chained to his enslaver’s bed and depicts the enslaver as sexually degenerate, engaging in “freaks of despotism” and “of a nature too filthy to be repeated.”

I situate this account within a broader discussion of Black men who were enslaved as valets or body servants, a group that one can view as having greater autonomy or improved living conditions than Black men who were forced to labor in fields. Similar to the understanding of field versus house conditions for enslaved women — where field labor provided harsher conditions, but somewhat removed from enslavers, and house labor, which carried the constant scrutiny of enslavers — Black men enslaved as body or man servants placed them within closer proximity to their enslavers, which increased their vulnerability and exposure to sexual scrutiny and likely abuse.

In what ways does your book deal with the issue of rethinking Black male masculinity? I’m thinking about how difficult it would have been to nurture a sense of Black male masculinity under conditions of emasculation. Exposure to sexual assault — to the hegemonic power and sexual whims of white men and white women — had to shape how enslaved Black men understood their masculinity, especially when compared to 19th-century models of manhood that emphasized independence, patriarchal authority, and the ability to protect and provide.

Many Black men expressed pride in fathering children and in seeking intimacy with women, especially in moments when some degree of choice or autonomy was possible. In some cases, accounts of forced reproduction — including situations in which enslaved men were rented out to impregnate women on other plantations — were described in relatively positive terms.

Those descriptions, however, must be understood within a cultural and legal environment that systematically denigrated Black men and subjected them to wide-ranging violations. Expressions of pride or resilience do not negate coercion. Some men mobilized strategies of endurance to survive being objectified, violated, and controlled. Survival and adaptation should not be mistaken for emotional immunity; many enslaved men likely carried the psychic weight of these violations in ways the archive can only partially reveal.

You state that your text “does not equate the sexual assault of women with that of men.” I would add that sexual assault experienced by Black enslaved men and Black enslaved women should not be seen as a zero-sum situation. Both experienced deep sexual terror. In your view, what has to shift in U.S. culture to avoid the assumption that Black men had it easy — or easier — under slavery when it comes to sexual exploitation, assault, and trauma? I ask this with no intention of downplaying the brutal sexual treatment of Black women.

It requires a willingness to move beyond familiar narratives and to sit with the complexity of what it means to be a victim and what it means to be a perpetrator under slavery.

In Rethinking Rufus, Rose was violated by Rufus and by the man who enslaved them both, who set the assault in motion. She endured pregnancy, likely ongoing violations, and physically punishing labor during pregnancy, which was not uncommon. Rufus was violated by the white man who enslaved them both, by being forced into that situation and used to fulfill the enslaver’s directive. Another example that illustrates multilayered victimhood and vulnerability comes from late 18th-century Maryland, whereby an enslaved Black man was forced at gunpoint to rape a free Black woman. Both were forced to have sexual intercourse by pistol-wielding white men, raising the issue of a definition of rape and sexual assault that until very recently had relied upon penetration and ignored forcing a man to penetrate. Yet one can imagine in the abstract that if you took a case of a woman wielding power to coerce or force a man to penetrate her, most would say that he was indeed sexually violated.

Taking the vulnerability of enslaved men seriously also allows us to reread sexual relationships between white women and enslaved men through the lens of power rather than through transhistorical assumptions about desire across the color line. One vivid example in the book comes from a legal case in North Carolina around 1840 involving a white woman and a Black man who lived together. The court focused on property rights after the relationship ended, but neighbors’ testimony revealed the power imbalance, including accounts that when the couple fought, she threatened to sell him.

By focusing on individuals and their lived experiences, we gain a clearer understanding of specific circumstances and of the additional pressures that the sexual vulnerability of enslaved Black men placed on their families and communities. It touched the lives of many others in addition to the men themselves. Thank you again for this opportunity to share a little about Rethinking Rufus.

First published in Truthout. This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

GEORGE YANCY is the Samuel Candler Dobbs professor of philosophy at Emory University and a Montgomery fellow at Dartmouth College. He is also the University of Pennsylvania’s inaugural fellow in the Provost’s Distinguished Faculty Fellowship Program (2019-2020 academic year). He is the author, editor and co-editor of over 25 books, including Black Bodies, White Gazes; Look, A White; Backlash: What Happens When We Talk Honestly about Racism in America; and Across Black Spaces: Essays and Interviews from an American Philosopher published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2020. His most recent books include a collection of critical interviews entitled, Until Our Lungs Give Out: Conversations on Race, Justice, and the Future (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023), and a coedited book (with philosopher Bill Bywater) entitled, In Sheep’s Clothing: The Idolatry of White Christian Nationalism(Roman & Littlefield, 2024).

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A powerful article on a fully neglected topic. Thanks so much to Prof. Yancy and his interviewee, author/Prof. Foster, for this piece. Much gratitude, too, to Michael for republishing it for the Vox Populi readership. My grandfather (1890-1974) was deeply troubled by the brutality of his/our family’s history and only at the end of his life spoke of certain “humiliating” aspects. He showed my mother 8 tintype photographs of enslaved couples being forced to breed in the presence of the plantation owner and his armed foreman. These tintypes were used as legal documentation in courts of law should the pictured slaves or their offspring try to escape. I was in college in 1974 and would never have been allowed to view such horror. My grandfather likely kept these hidden in a strong box in the basement. I have no idea what became of these historical items. All of my elders are gone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A powerful article on a fully neglected topic. Thanks so much to Prof. Yancy and his interviewee, author/Prof. Foster, for this piece. Much gratitude, too, to Michael for republishing it for the Vox Populi readership. My grandfather (1890-1974) was deeply troubled by the brutality of his/our family’s history and only at the end of his life spoke of certain “humiliating” aspects. He showed my mother 8 tintype photographs of enslaved couples being forced to breed in the presence of the plantation owner and his armed foreman. These tintypes were used as legal documentation in courts of law should the pictured slaves or their offspring try to escape. I was in college in 1974 and would never have been allowed to view such horror. My grandfather likely kept these hidden in a strong box in the basement. I have no idea what became of these historical items. All of my elders are gone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for sharing this, Desne. I think that America is still in denial about the horrors of slavery.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Erasing this history is erasing the lessons that are needed for humanity to grow morally and that appears to be the point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

exactly. We wouldn’t have Trump if people had remembered Hitler.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tears in my eyes a few times, reading this. What an essential article/essay — this should be taught in high school all over the country!

LikeLiked by 2 people