Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

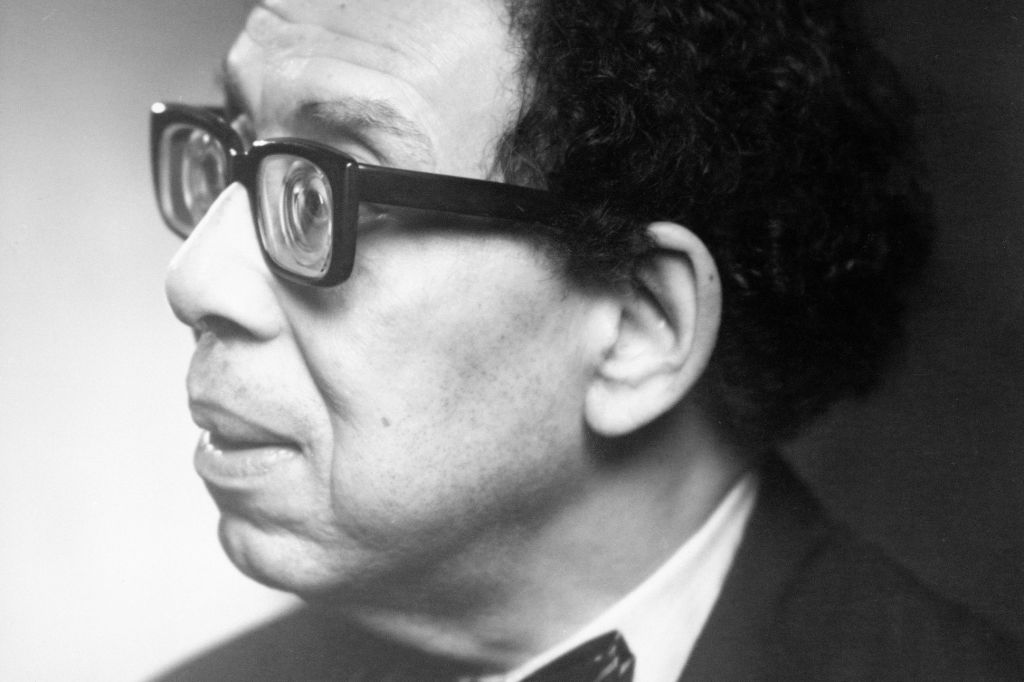

Robert Hayden: Those Winter Sundays

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

~~~~

© 1966 by Robert Hayden, from COLLECTED POEMS OF ROBERT HAYDEN by Robert Hayden, edited by Frederick Glaysher (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 1966).

Robert Hayden (1913 – 1980) was born in Detroit, Michigan, to Ruth and Asa Sheffey, who separated before his birth. He was taken in by a foster family next door, Sue Ellen Westerfield and William Hayden, and grew up in the Detroit neighborhood called “Paradise Valley”.

His childhood traumas resulted in debilitating bouts of depression that he later called “my dark nights of the soul”. Because he was nearsighted and slight of stature, he was often ostracized by his peers. In response, Hayden read voraciously, developing both an ear and an eye for transformative qualities in literature. He attended Detroit City College (later called Wayne State University) with a major in Spanish and minor in English and left in 1936 during the Great Depression, one credit short of finishing his degree, to go to work for the Works Progress Administration Federal Writers’ Project, where he researched black history and folk culture.

Leaving the Federal Writers’ Project in 1938, Hayden married Erma Morris in 1940 and published his first volume, Heart-Shape in the Dust (1940). He enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1941 and won a Hopwood Award there. Raised as a Baptist, he followed his wife into the Bahá’í Faith during the early 1940s, and raised a daughter, Maia, in the religion. Hayden became one of the best-known Bahá’í poets. Erma Hayden was a pianist and composer and served as supervisor of music for Nashville public schools.

In pursuit of a master’s degree, Hayden studied under W. H. Auden, who directed his attention to issues of poetic form, technique, and artistic discipline. Auden’s influence may be seen in the “technical pith of Hayden’s verse”. After finishing his degree in 1942, then teaching several years at the University of Michigan, Hayden went to Fisk University in 1946, where he remained for 23 years, returning to the University of Michigan in 1969 to complete his teaching career (1969-80).

By the 1960s and the rise of the Black Arts Movement, when a more youthful era of Afro-American artists composed politically and emotionally charged protest poetry overwhelmingly coordinated to a black audience, Hayden’s philosophy about the function of poetry and the way he characterized himself as an author were settled. Hayden stayed consistent with his idea of poetry as an artistic frame instead of a polemical demonstration and to his conviction that poetry ought to, in addition to other things, address the qualities shared by mankind, including social injustice.

His work often addressed the plight of African Americans, usually using his former home of Paradise Valley slum as a backdrop, as he does in the poem “Heart-Shape in the Dust”. He made ready use of black vernacular and folk speech, and he wrote political poetry as well, including a sequence on the Vietnam War.

The impact of Euro-American innovation on Hayden’s poetry and also his continuous assertions that he needed to be viewed as an “American poet” as opposed to a “black poet” prompted much feedback of him as an abstract “Uncle Tom” by Afro-American critics during the 1960s. However, Afro-American history, contemporary black figures, for example, Malcolm X, and Afro-American communities, especially Hayden’s native Paradise Valley, were the subjects of a significant number of his poems.

On April 7, 1966, Hayden’s Ballad of Remembrance was awarded, by unanimous vote, the Grand Prize for Poetry at the first World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal. The festival had more than ten thousand people from thirty-seven nations in attendance. However, on April 22, 1966, Hayden was denounced at a Fisk University conference of black writers by a group of young protest poets led by Melvin Tolson for refusing to identify himself as a black poet.

Hayden was elected to the American Academy of Poets in 1975.

[bio adapted from Wiki]

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

41 comments on “Robert Hayden: Those Winter Sundays”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on February 1, 2026 by Vox Populi in Most Popular, Opinion Leaders, Poetry, Social Justice, spirituality and tagged Black poets, BLM, fathers and sons, poverty, Robert Hayden, Those Winter Sundays, Winter.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-rAWSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,952,781

This is one of my all-time favorite poems and I have a story about it– wish I could have shared it with Hayden when he was still alive. When I was teaching Computer Science at UF I used to post a poem on my door (never mine) and if a student wanted my help, he/she was required to read it first. One day a kid came in with his program under his arm, and when I said, so what’s going on with your program? he said I’m not here about that any more. I said, so why ARE you here? And he said, I read the poem on your door. And I said, it’s a beautiful poem isn’t it? And he said yes it is, then he went straight to his car and drove the 2 1/2 hours to his father’s grave in Tampa, to tell him he was sorry, that he understands now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my, Lola. What a beautiful story about the power of poetry. Thank you.

LikeLike

Well, you know, I have other powerful stories about how a poem has changed, even in one case, saved, someone’s life. I believe in its power so deeply that I could stand on a streetcorner and preach it.

LikeLike

Amazing, Lola!

LikeLike

Yes, I can well imagine that this poem has such power.

LikeLike

I’ve loved this poem since the first time I read it. I printed it, folded the paper and carried it with me for a couple of weeks, reading it over and over whenever I was still.

LikeLike

Yes, thank you, HC.

LikeLike

I have loved this poem since I first read it, only a few years ago. I just read through everyone’s comments about the poem and their relationship to it. These conversations are worth reading, and since I tend to get to catching up here later in the day than many, I may see more of what’s being said. Some of today’s comments have given me an idea of how to possibly approach my father’s story, which I keep writing about, especially in the last few years, differently. Thank you for the conversation, as well as the posting of the poem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Penelope.

LikeLike

A never-endingly brilliant poem. How can so much nuance and complexity be packed, without evident labor after effect, into fourteen lines?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is extraordinary how the poem yields new associations with each reading.

LikeLike

I agree with, & thank every one for such engaged and grateful replies. I, like many, have been teaching and loving this poem for decades, and still have to meet a student (adult or teenager) who isn’t deeply touched by this poem. Isn’t it true that some poems truly become part of us. This one certainly is part of me.

LikeLiked by 3 people

me too!

LikeLike

This semester I have not been able to return as a student to my beloved poetry classes, but this poem was presented in two of them and remains a favorite. I picture my grandfather when my dad was a child in North Dakota, the stories that make the connection for someone who has spent very little of her life in cold and snow, but recognizes how much love is given without explanation or words.

LikeLiked by 3 people

It’s okay, Barb. We’ll be your poetry class as long as you need us.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I will always need this family I fell into. The beauty of words and the humane vision start my day when I could easily slip back under the covers and hide.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Every time I read this poem I get a big lump in my throat, thinking of my grandfather and my mother making the fires blase to protect us from that blue-black cold. And, no, we didn’t thank them. “What did we know… “What did I know, what did I know / of love’s austere and lonely offices?” This is possibly one of my ten favourite poems of all the poems I’ve ever read. Its content, its power, its craft, its solemn music… its ability to live under my skin.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This poem has lived under my skin for a long time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For my money, this is one of the best poems of the 20th century. The repetition of “What did I know” kills me every time. I could write an essay, but far better to let the poem speak for itself. Thanks, Robert. Thanks, Vox Populi.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Charles!

LikeLike

This is a wonderful poem. Thanks for posting it again, Michael.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ever since I first read this poem many years ago, I have thought that everyone should learn to ask that last question, should learn about ‘love’s austere and lonely offices’. It has helped me to have more compassion, even now.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Jan. I have had the exact same experience with the poem. It has helped me to have more tolerance for my own father who was a difficult sometimes violent man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed! This poem has been a long time favorite as it directs the reader to their own inner view of their life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is one of my favorite poems. It’s simplicity holds such deep love. We read this at my father’s funeral. Thank you, Michael, for sharing this with us.

LikeLiked by 4 people

How wonderful that your family read the poem at your father’s funeral. I wish I had thought of doing that at my father’s funeral.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This poem moves me every single time. Thank you, Michael, for choosing it for this winter Sunday.

LikeLiked by 4 people

I’ve read this poem to myself at least a hundred times, and I used to recite it to my students to wow them. It is arguably the best poem ever written by an American.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Michael, I was just going to say the same thing! It is a perfect poem. I return to it over and over. Definitely my favorite American poem.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I remember teaching this poem in my Modern American Lit classes. The students loved it, loved it for the way he talked about the cold and the way he talked about his family life.

haven’t read it for years. Thank you for posting it and reminding me how good a poet he was.

LikeLiked by 4 people

My students loved it too.

LikeLiked by 3 people

i run out of words before I run out of wonder of this poem. What would poetry be without it? This is the day for this poem: 27 degrees outside—Its been 20 years, We now watch our children in their parenthood. Yesterday in the dark with a flashlight, I picked greens that had come up in the swale-bottom of the pasture along the road knowing they’ll be ransacked by the cold this morning. It was the last chance of the winter to gather them. We’d been waiting a month for rain and this cold is all that’s come. They wait On the diningroom table in a green bundle, I’ll cook them as the sun comes up.

LikeLiked by 8 people

the cold? Here in Virginia I’ve been stuck in the house for almost two weeks. The streets haven’t been plowed. The snow and ice and wind and cold make it impossible to get to the mailbox. Thankfully the mail isn’t being delivered.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I suppose its always in frames of reference of our lives. My urgency is based on keeping 300 cows and calves in grass. We just lost it all this week. What do we do next?

I wish I could say, but for now, the pot is on the stove, orb in the sky,

…Two poets speaking

LikeLiked by 4 people

Yes, frame of reference. I grew up in Chicago. When I would complained about the snow and cold, my dad would laugh. He had spent 4 years as a prisoner in Buchenwald concentration camp. Here’s a piece I wrote about it.

Winters in Buchenwald

He remembered the frozen bodies.

Some looked like they had been cemented in the ice, heads and hands and knees above the ice line, stomachs and feet below.

The prisoners who died this way must have been trying to raise themselves out of the freezing water, but the water froze too quickly.

Some of the living prisoners peeled coats and pants from the bodies of the frozen dead, but my father didn’t.

He stood there staring at the dead. Their legs were black with frostbite, their pricks shriveled to the size of acorns.

He never forgot the lesson he learned. A frozen naked man was a miserable thing.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks for your powerful witness, crafted well, and Like Hayden’s poem, the ending overwhelms. How some of us turn humans into things. The first word of your poem He, while the last word is thing. and the two separated by his witness (and your and his beautiful compassion).

LikeLiked by 2 people

thank you. I’ve never noticed that conflict between the first and last word.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A powerful poem, John. Thank you for sharing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. When I traveled to the camps during a trip to a Polish medical school, it was winter and I felt I was walking through some sort of evil gel. By the time I was back on the bus, I was different, shaking then, and the horror has somehow become a weight that has stayed with me. I think it feeds the fear I have now that makes me make the comparisons that people deny or even become angry that I am somehow lessening that evil. But the evil didn’t start that way and I see too many similarities to ignore. When I arrived in Poland, ice crystals hung from the trees. Was it really 40 below or have I exaggerated it over the years? Beauty in the cold. The heaviness that remains even though I also remember a welcoming Jewish community, music , their warmth.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Beautiful prose, Barb. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for Vox Populi.

LikeLiked by 1 person