Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Philip Levine: The Poem of Chalk

On the way to lower Broadway

this morning I faced a tall man

speaking to a piece of chalk

held in his right hand. The left

was open, and it kept the beat,

for his speech had a rhythm,

was a chant or dance, perhaps

even a poem in French, for he

was from Senegal and spoke French

so slowly and precisely that I

could understand as though

hurled back fifty years to my

high school classroom. A slender man,

elegant in his manner, neatly dressed

in the remnants of two blue suits,

his tie fixed squarely, his white shirt

spotless though unironed. He knew

the whole history of chalk, not only

of this particular piece, but also

the chalk with which I wrote

my name the day they welcomed

me back to school after the death

of my father. He knew feldspar,

he knew calcium, oyster shells, he

knew what creatures had given

their spines to become the dust time

pressed into these perfect cones,

he knew the sadness of classrooms

in December when the light fails

early and the words on the blackboard

abandon their grammar and sense

and then even their shapes so that

each letter points in every direction

at once and means nothing at all.

At first I thought his short beard

was frosted with chalk; as we stood

face to face, no more than a foot

apart, I saw the hairs were white,

for though youthful in his gestures

he was, like me, an aging man, though

far nobler in appearance with his high

carved cheekbones, his broad shoulders,

and clear dark eyes. He had the bearing

of a king of lower Broadway, someone

out of the mind of Shakespeare or

Garcia Lorca, someone for whom loss

had sweetened into charity. We stood

for that one long minute, the two

of us sharing the final poem of chalk

while the great city raged around

us, and then the poem ended, as all

poems do, and his left hand dropped

to his side abruptly and he handed

me the piece of chalk. I bowed,

knowing how large a gift this was

and wrote my thanks on the air

where it might be heard forever

below the sea shell’s stiffening cry.

~~~~

Copyright 2014 Philip Levine. From The Simple Truth (Knopf, 2014).

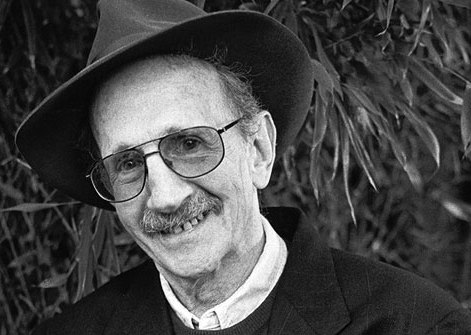

Philip Levine (1928 – 2015) was best known for his poems about working-class Detroit. He taught for more than thirty years in the English department of California State University, Fresno and held teaching positions at other universities as well. He served on the Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets from 2000 to 2006, and was appointed Poet Laureate of the United States for 2011–2012. [adapted from Wiki]

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

29 comments on “Philip Levine: The Poem of Chalk”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on January 23, 2026 by Vox Populi in Most Popular, Opinion Leaders, Poetry, Social Justice and tagged Philip Levine, The Poem of Chalk.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-pKLSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,960,490

I love Levine’s poetry. We just read the poem “What Work Is” in my poetry class. I miss that guy. I’m glad we have his poems to keep his world with us.

LikeLike

I love that poem of Phil’s as well.

>

LikeLike

Great to see this poem from one of the greats. Charles ________________________________

LikeLike

Yes, he is!

>

LikeLike

I echo the thanks to Margo for her brilliant comments — I love Phil Levine, was lucky enough to go to at least 20 readings of his when Kurt and I lived in NY. And each time, every single time, I was amazed by his true, absolute authenticity & love & pride for the working class. He also had a wicked sense of humor — and when he and Jerry Stern would share a reading together: oh my, the fireworks!

LikeLike

Thanks, Laure-Anne!

>

LikeLike

Loved listening to the video

LikeLiked by 2 people

me too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a gorgeous poem. Levine is one of my all-time favorites and I know no other poet who reads their own poems so beautifully. His readings often give me the shivers. Thank you for posting.

I did some digging and found a video of him reading this poem. He starts at 2:32.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Tony.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

A favorite poet at the height of his powers.

In his hands, a poem about chalk is not merely an amiable tale, but a blessing to us readers, and to the giver of the chalk. To me, it hints at resilience and enduring pain, while finding meaning in this little culture the two people created through their dialogue. This was true of many others of his poems as well.

Thanks for this poem. Levine did good work, and still matters.

LikeLiked by 3 people

One of our best poets.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Long a favorite of mine.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The mind’s picture so clearly drawn, I almost felt the chalk in my hand. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 3 people

This poems is perfect in its simplicity. I am there, I see the man, regal and elegant, reciting a poem to the chalk. Levine transforms that moment into a magical event. I want to be there.

LikeLiked by 4 people

‘Levine transforms that moment into a magical event.’ Exactly. Thank you, Rose Mary.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sometimes, when I read a poem by Philip Levine, I am so staggered and awed, so dazzled by the brilliant simplicity that I have to read the piece over and over, aloud but to myself, until all the elements of the piece click into place and I am left with nothing but gratitude for the gift. “thanks on the air” indeed.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Annie. Well-said. I feel the same way about his poems.

LikeLiked by 3 people

One of my Phil favorites, wonderful to read not long after his birthday.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He was great. Such clarity and passion.

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this one, at this moment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Thomas.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

How he gets us to his school’s chalkboard opens everything so much wider.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Yes!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes this is so wonderfully complete, has that nuance of a stream flowing at such careful pace through its banks of the soul. He was nothing if not soulful. The poem makes us all complete this morning and able to go on about our day full of the thing we’d otherwise for lack of, be dying.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Poetry gives its gifts in small gatherings of words to feed our starving hearts… a few days ago here… Sean Sexton said of the words for the goats… “Only children and angels would say such a thing.” Today, Philip Levine ends with “my thanks on the air/where it might be heard forever/ below the sea shell’s stiffening cry.”… And as Shakespeare whispered for us…”such things as dreams are made of…”… May the invisible be written in air and in chalk and in chant and in french and other tongues… even in such dark days as ours.

LikeLiked by 6 people

So beautifully said Margo!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this wisdom, Margo!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this, Margo.

LikeLiked by 1 person