Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Michael Simms: Serenity Park

Mikey’s directions were perfect, and Jesse arrived at Serenity Park in just a few minutes.

It was a lovely place with parents pushing strollers and leading small children. There was a skateboard park where the older boys and a few girls were doing impossibly dangerous tricks. And there were trees! Jesse felt he could breathe again. The bird sanctuary was a corridor of wire-meshed enclosures where the parrots paced and rocked and screamed. Jesse loved parrots, and he knew that the birds don’t just mimic human language, they speak and understand the languages of their owners. But standing in front of the green, white, blue, red, and yellow birds and listening to them, Jesse realized that these birds, at least many of them, were sad, old, and mentally ill. They had been traumatized twice, once by being taken from their homes in the rain forest, and then, having adjusted to the companionship of a human, they’d lost that connection as well. Now they were behind bars with parrots they had nothing in common with. Bullying and violence were common among the birds, and only the ones who’d found something to do, such as stack pebbles into pyramids or carve their food into sculptures had managed to retain their sanity.

Jesse walked slowly in front of the cages, listening to each bird. He stopped in front of Julius, a peach-white Moluccan cockatoo with a pink-feathered headdress, who was madly pacing, muttering in Korean. Julius was surprised and pleased when Jesse spoke Korean to him. He immediately calmed down and explained that he hadn’t spoken to anyone in years. He’d been taken from the nest when he was a fledgling and never learned any of the parrot languages. When the Korean woman whom he lived with died, her daughter kindly brought Julius here, not realizing that Julius would never fit in with other parrots. Jesse stroked Julius behind his head, reassuring him that things would work out; then he walked in front of the mesh cages, introducing himself. He met a blue-and-gold macaw named Bacardi who kept calling out for someone named Muffin, and Pinky, a Goffin’s cockatoo who’d been brought here by a woman whose husband threatened to cut the wings off the bird to spite his wife. Pinky seemed to be imitating the sound of a power saw which added to the ungodly racket coming from the cages. The problem, Jesse realized, was that the birds were imitating each other, so the power saw sound was coming from multiple birds. Phrases like “Whoa, come on!” and “Hey, sweetie!” came from more than one bird. It seemed that one of them had learned a few showtunes and taught them to the other parrots, so Jesse heard phrases from “Oklahoma” and “Cats” coming from multiple throats. As Jesse began to sort out the threads of noise, he wondered what was the purpose of having all these traumatized birds in one place?

A heavy-set young woman in blue jeans and tee-shirt used a key to open one of the cages. On a cart she had a broom, a mop, bags of bird seed, walnuts, peanuts and Brazil nuts in their shells, and pieces of apple, orange and melon. She went from one cage to the next, filling bowls with food, and the parrots flocked down, grabbing with their claws or beaks a piece of fruit or a nut or a mouthful of seeds and returning to their perches to eat. The woman was missing her right hand, but she deftly managed with her metal prothesis to sweep and mop each of the floors, stopping every now and then to talk to a bird or to stroke their feathers. The birds were calm, eating their lunch and enjoying her company. After the cacophonous noise, the silence seemed peaceful, but a little eerie.

When the young woman finished her chores and was packing up her cart, Jesse approached her. “Hi!” he said, trying to sound friendly.

She turned her dark head toward him, noticing him for the first time, and said, “Hi.”

“Do you work here?” he asked.

“Yeah, I’m in work therapy at the VA.” She cocked her head toward a large building nearby.

“So, you take care of the birds as a way of healing yourself?”

“Say, you’re pretty smart for a little kid,” she said, smiling at him warmly.

Jesse liked this woman immediately. He knew she would appear fat, even obese, to men, but he could tell by her graceful smooth movements that she was actually very powerful. Her muscles rippled in her left arm as she worked. Despite her missing hand, she reminded Jesse of a jaguar, one of his favorite animals.

‘‘You can look in their eyes,’’ the woman said. “And see a soul, and when they look at you, they see right into your soul. Look at them. They’re watching us. It’s intense.”

“How’d you lose your hand?” Jesse asked, but regretted asking when he felt a flush of anger wash through her. That moment of serenity she’d had when she thought about the birds now eluded her. He felt her struggle with anger, then fear, relief, gratitude and finally acceptance. This was a very special young woman, he realized. He wondered whether he’d met her before. Then he remembered how he knew her.

“I was in Iraq. It was a helicopter crash. I was lucky to survive.”

“Were you addicted to drugs afterward?”

She turned to him with surprise on her face. “Do I know you?”

“Not exactly. I knew your mother.”

“My mother’s been dead for a while. What are you, about twelve? You probably didn’t know my mother.”

“I’m older than I look. Your mother’s name was Maria Sequevar, and she was killed by her boyfriend three years ago.”

“I guess you did know my mother. How’d you meet her?”

“We met in church. St Mary’s over in Boyle Heights.”

“Yeah, that was her church,” Marta turned her cart and started pushing it toward the hospital.

“Marta, I need to tell you something,” Jesse said. When she didn’t stop, he said, “Don’t do it, Marta.”

“Don’t do what?” she asked turning her head partway toward him.

Jesse walked up to her and said softly, “Don’t kill him.”

“Don’t kill who? What are you talking about? You are one weird kid, aren’t you?”

“Don’t kill Rogério, your mother’s boyfriend. Leave his punishment to God.”

“Don’t worry,” she said. “I’m not going to kill that bastard. Wait a minute… how do you know this stuff about me? Who are you? Are you a mind-reader or something?”

“No, I’m not a mind-reader, but I can tell what’s in a person’s heart, and I know you stopped saying your prayers when your mother died, and instead you go to sleep every night fantasizing about killing Rogério. You need to go back to saying your prayers.”

“I’m not planning to kill him.” She turned away. “Stay away from me, you little creep.”

“You’re killing him in your heart every night, Marta,” Jesse shouted after her. “And this hatred is killing you. You need to forgive him to save yourself.”

Maria turned back to Jesse, looked around the park, and shrugged her shoulders. “This is a dream, right? A twelve-year-old kid who can read what’s in my heart?”

“No, this is not a dream. Well, actually everything is a dream, but not in the way you mean. Tomorrow morning you’ll wake up, remember this, and think it was a dream. But it’s a dream you need to listen to. Free yourself, Marta. Leave Rogério to God.”

Marta gave Jesse an exasperated look, rolled her eyes, shook her head, took hold of her cart, and pushed it toward the hospital. Jesse watched her walk away, then turned his attention back to the unhappy parrots. Obviously, what they needed was an activity that would bond them into a community. He thought about teaching them a common language such as Esperanto, but it would take weeks, and he didn’t have time. Perhaps they can sing together? Or wait a minute, a drumming circle! They already had a sense of rhythm, and they could use the cage itself as a drum.

He started by explaining to Julius in Korean what he wanted to do. Jesse banged on a bar of the cage a basic 1,2,3,4 beat which Julius imitated by tapping his claw on the wire mesh. Jesse praised him, then changed the 1 and 3 to a short Yeah which Julius imitated. Then Jesse moved a few feet to Bacardi and explained in Creole that he wanted him to fill out the rhythm by shouting Muffin between Julius’ beats, so it sounded like tap Muffin Yeah, tap Muffin Yeah, tap Muffin Yeah, tap Muffin Yeah. Then Jesse went to Pinky and asked her to flap her wings and imitate a power saw with a short burst on the 1 and 3 notes. By now, the other parrots were listening, fascinated that the three birds were synchronizing their sounds into a pattern. On the far side of the cage, a large white cockatoo started imitating the entire composition, coming in perfectly on time on every third cycle, filling out the sound, and then other birds began to get the hang of it, piping, shouting, roaring, and saying their favorite phrases in rhythm with the other birds. Now that the parrots understood the principle of coordinating their calls into a rhythmic composition, Jesse knew that the birds would continue evolving the sound. He turned and walked away, hearing the paracletic music growing louder and more complex by the moment. Out of the chaos of the parrots’ desperate calls had emerged a texture of beautiful sound, and none of them would ever be lonely again.

~~~~~

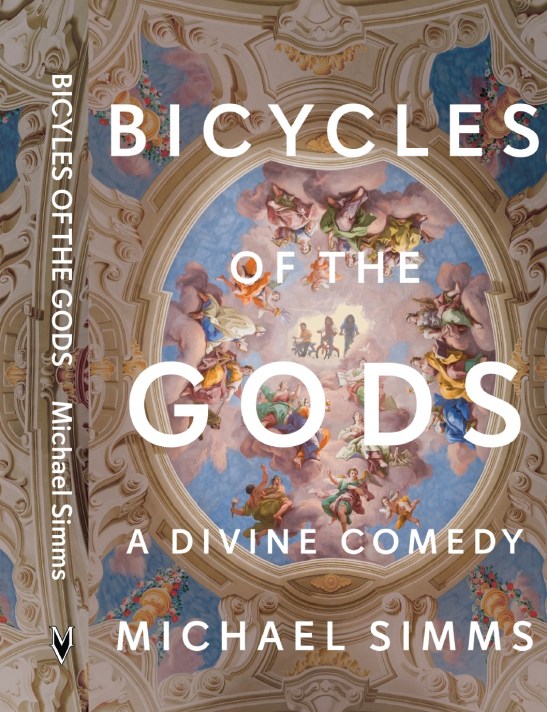

Copyright 2022. From the novel Bicycles of the Gods: A Divine Comedy by Michael Simms Madville, 2022). The sequel, The Hummingbird War, will be released in March 2026 and is available for preorder now.

Paper, Kindle and audio books by Michael Simms are on sale at Amazon now. Prices as low as $.98.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I read this post a day late and marvel at its fairytale quality, understanding as well how very real are its terms and telling. The purpose of religion is to teach you everything is alive. I have taken a further step in my spiritual development having received this lovely story. Perfect timing for me!

LikeLike

Wow! Thank you, Sean!

>

LikeLike

Wonderful. I was mesmerized. I’m about to forward this to a bird-loving friend who lives with two parrots and feeds wild birds around her home.

LikeLike

Thank you, Penelope!

>

LikeLike

I often hear those birds, like you do, Michael, old Bacardi, Muffin, and Pinky. And other’s who live in my jacaranda tree, but who insist on remaining anonymous. They told me to tell no one, because I wouldn’t be believed.

(I loved re-reading this passage!)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Laure-Anne! I’m so glad that Jesse could help the birds heal each other through music.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael, you re so good at knowing what will be healing.

LikeLike

Thank you, Barbara. I count on you every day.

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

I felt transported reading this, helping me forget about ICE and the dark news.

‘‘You can look in their eyes,’’ the woman said. “And see a soul, and when they look at you, they see right into your soul. Look at them. They’re watching us. It’s intense.”

Thank you, Michael.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you!!!!

>

LikeLike

What an amazing, wonderful idea, Michael. I am listening to those birds!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Rose Mary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. ❤️

LikeLiked by 2 people

😘

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a world of takers and givers, where survival of the life-force depends upon a symphony syncopated on the bars of our cages.

Serenity is a returning. I remember the time a Merlin hawk welcomed me home.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lovely poem, Jim. Thank you for this gift.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful, Michael, and such a poignant pairing today — the excerpt from your novel and the driving-instructor film. Teaching. Learning. Living.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Christine!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person