Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

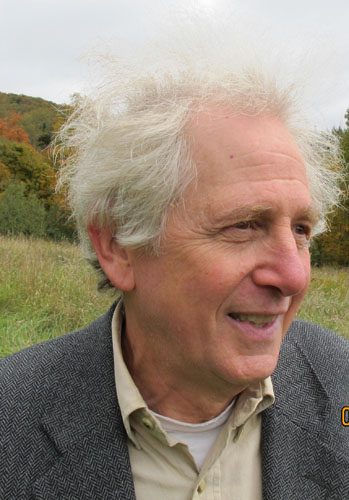

Baron Wormser: The Refusal

On April 16, 1851, Herman Melville wrote a letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne in which he praised Hawthorne’s new book, The House of The Seven Gables. His esteem for Hawthorne was very high: “There is a certain tragic phase of humanity which, in our opinion, was never more powerfully embodied than by Hawthorne.” Melville went on to write some words that speak across the years to the predicament of the American writer: “There is the grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says NO! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes. For all men who say yes, lie and all men who say no, – why they are in the happy condition of judicious, unencumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag – that is to say, the Ego.” One assumes that Hawthorne, whose replies to Melville’s enthusiasms were scant, knew what his writer-friend was talking about.

It’s a remarkable statement that Melville makes. We take, rightly so, poets and writers as people who, in some way, shape, or form, are involved in praising the sheer energy of Being and, in that regard, are saying yes to the life force. I don’t think Melville would have quibbled with that variety of yea-saying. After all, Melville was at work on a book about a whale, a book that contained many pages reveling in the being of that creature. What Melville was aiming at was the glib, socialized way of being, not just the going-along to get-along but the fulsome words that insisted each day on the unalterable wisdom of whatever social schemes the era was trumpeting. Melville and Hawthorne knew that humankind was wont to not only persist in wrongheadedness but to brag about it and cheer it on. You can see what I mean about Melville’s words reverberating in this present day.

Given the socialized expectations that attend every step of life – as in “You don’t really mean that, do you, Herman?” – we can appreciate those capital letters. Hawthorne of course was sly and evasive. He was not one to confront the world directly. He had novels to write in which he could play out scenarios that were so quietly dark as to verge, as Melville noted, on the tragic – an unheard of quality in American letters at that time and still a very rare one many years later. What could be tragic about a nation of boosters, inventors, schemers, and fixers? Yes, precisely that. All the flatulent assertions certainly got under Melville’s skin. For beneath the surface something lethal lurked, something you should not say yes to, something that if you did say yes to meant that you were imperiling your very soul because you were surrendering the distinctness of your being, the honesty of your responses, for the sorry payment of social approval and whatever self-righteousness that approval bestowed upon you. A mean fate but one that was typically greeted with a smile and a hearty handshake.

To say that “NO!” is scary. Such refusal takes courage. It is not what anyone wants to hear. It spoils the party and opens the naysayer to a host of unhappy epithets – pessimist, cynic, loser, grudge bearer, grumbler. All in all, not, as they like to say in America, “a team player.” As to why a poet or writer should want to be a team player is one more socialized story that a world of writing programs speaks to more or less eloquently. As a sailor, Melville would acknowledge the truth of any port in a storm, the storm being one of commercial progress eager to obliterate everything in its path and cry down every protest as backward. The role, however, which poets and writers can fill, a crucial role however much the society-at-large dismisses the role, is precisely that of naysayer, of someone who refuses to go along with the daily verbiage, whether it be bland or vociferous. The notion is that poets and writers live and die by their words. Indeed, some, as with Melville and Hawthorne, really meant it.

For my part, I think of some of the American poets of the mid-twentieth century who were fearless in their refusal to go along. I’m referring specifically to Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, John Berryman, and the lesser known Weldon Kees, who seemed like a Hawthorne character come to life. I could cite others, some of the so-called Beats come to mind, though the likes of Allen Ginsberg was glad to make his way in the world and welcomed the attention. He enjoyed his aura. The poets I am speaking of were, despite the ambitions they harbored, very equivocal about what the age offered them. The women knew it all could be taken away in a dismissive second. The men knew that beneath many a compliment lurked a knife, be it of belittlement or envy. “Who are you?” “How dare you?” The questions hung in the conformist air and stifled many an impulse.

When one looks then at Plath’s outright fierceness, at Sexton’s subversive imagination, at Berryman’s talent for mockery, at Kees’s quiet subterfuge as embodied by his Robinson poems (“Curtains drawn back, the door ajar / All winter long it seemed a darkening / Began.”), one feels a tenacity at work that will not be gainsaid. One feels a struggle has been joined, a struggle that speaks to the very integrity of the poetic enterprise. This can come as a surprise in America where integrity is associated with a declarative sincerity that can, with a determined poof, blow out the objectionable candles. Alas, what the poets to whom I am referring were aware of ran much deeper than any touted voice. Underneath the amiable, glad-handing exterior of American life lurked terrors. Melville and Hawthorne knew of what they wrote. Their writing gives the pleasure of accomplished artistry but they did not write to please.

Thus when one looks, for instance, at Plath’s “The Applicant,” one finds a tone in which cheeky ferocity feels quite natural since it takes off from the competitive, unforgiving, demeaning tenor of American business. Her laser intelligence is right there in the poem’s wonderfully overbearing first line: “First, are you our sort of a person?” Other questions loom: “Open your hand. Empty? Empty?” and the famous “Will you marry it?” We are not talking in the latter question about a “him,” as one might expect in Plath’s era. No, we are dealing with “it,” a depersonalized, objective, in-the-world presence. The last stanza pushes the zaniness further: “It works, there is nothing wrong with it.” “Works.” What word could be more apposite to judge a human situation that doesn’t feel at all human? The last two lines complete the devastation: “My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” No question mark in that last line, just flat-out assertion. We are in the realm of what used to be called “black humor,” a genre Plath excelled at. She has taken her cues from the world and run with them. The pathos within the phrase “something’s missing” almost goes without saying. Underneath the brisk, no-nonsense tone is an abyss of thwarted feeling: “It is guaranteed / To thumb shut your eyes at the end / And dissolve of sorrow.”

Melville revered Hawthorne for his courage and I revere Plath and the other poets I have mentioned for their courage. Their courage was not an ideological position. Courage is an intensely personal matter. I don’t think it can be taught, however much armies try to instill it in soldiers. And courage exacts a price. It’s not a suit (an article of clothing Plath brings up in “The Applicant”). The world-at-large often looks the other way when a person exhibits courage, the fate of many a whistle-blower and freedom fighter testifies to that. It’s not a quality that falls in with “brilliant,” a word that comes readily off many tongues as a term of ultimate praise. As with Hawthorne, we are in a moral realm that is all too aware of the world’s amorality and immorality. Berryman joked endlessly about the plight of his Henry character in the “Dream Songs,” but in the end that plight wasn’t very funny, not was it for the other poets. Suicide was in the cards for all of them.

It is wrong, however, to define their achievements through that lens. The whole point, so to speak, of their writing is to argue against the glib judgments the world is so eager to thrust forward. Life, as the poets perceived it, tore at them and rent them. The well-meant avenues of compromise and consideration didn’t help. They were, for all the dynamism and shrewdness of their poetry, stuck. As Donald Justice noted in his preface to The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees, “If the whole of his poetry can be read as a denial of the values of the present civilization, as I believe it can, then the disappearance of Kees [his body was never found] becomes as symbolic an act as Rimbaud’s flight or Crane’s suicide.” Justice was a measured man who chose his words carefully. He was not making a cheap case for nonconformity or rebellion, much less for taking one’s life, but pointing to a cardinal fact based on many attributes.

At this point in time in the United States, where politics has swallowed morality and spat out a stream of truculence, where “values” are paraded as products, where posturing is so entrenched as to even banish hypocrisy, where violence is currency, and where character has been reduced to boasting, one has to feel that the poets knew what they were writing about. Melville, in another letter to Hawthorne, deserves the last word: “For in this world of lies, Truth is forced to fly like a scared white doe in the woodlands; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself, as in Shakespeare and other masters of the great Art of Telling the Truth, – even though it be covertly, and by snatches.”

Baron Wormser has received the Frederick Bock Prize from Poetry and the Kathryn A. Morton Prize along with fellowships from Bread Loaf, the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. In 2000 he was writer in residence at the University of South Dakota. Wormser founded the Frost Place Conference on Poetry and Teaching and also the Frost Place Seminar. For a list of his books, please click here.

Copyright 2024 Baron Wormser

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

9 comments on “Baron Wormser: The Refusal”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on November 10, 2024 by Vox Populi in Literary Criticism and Reviews, Most Popular, Opinion Leaders, Social Justice, spirituality and tagged Allen Ginsberg, Anne Sexton, authenticity, Baron Wormser, ethics, ethos, Herman Melville, John Berryman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Sylvia Plath, Weldon Kees.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-orESearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,953,744

Let’s hear it for the No! I appreciate BW reminding me to take to ship. Or to consider where, in fact, the devil resides. Thanks to the essayist who can create light and heat in the dark American forest.

LikeLike

Thanks, Adam.

>

LikeLike

Baron Wormser responds to the comments here: ” “I’d appreciate it if you just say ‘Thanks’ on my behalf. I tend to get balled up trying to go through the Internet response process. And thanks to you for doing that and for running this essay.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

Baron Wormser, as always, hits the infamous nail on its hypocritical head. I LOVE how your mind works, Baron Wormser – and your mastery at expressing it. Especially those last lines will stay with me for quite a while: ““For in this world of lies, Truth is forced to fly like a scared white doe in the woodlands; and only by cunning glimpses will she reveal herself.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

“At this point in time in the United States, where politics has swallowed morality and spat out a stream of truculence, where “values” are paraded as products, where posturing is so entrenched as to even banish hypocrisy, where violence is currency, and where character has been reduced to boasting, one has to feel that the poets knew what they were writing about. “

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Barbara. This quotation is exactly what I need to read as I recover from the election.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

As deft and accurate a summation as I ciuld imagine: that it comes from Baron, however, is scarcely a surprise; he’s always spot-on.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He really is. I love his essays.

>

LikeLiked by 1 person