Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

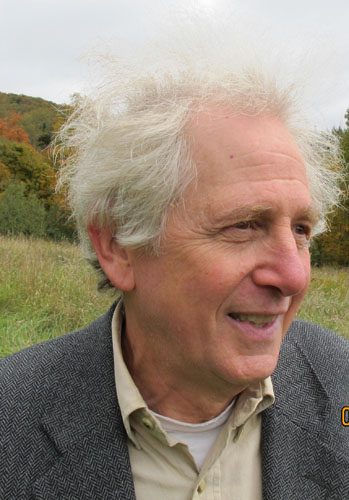

Baron Wormser: The System

Back in the day, I used to ascribe every woe to what I called “The System.” The woes were plentiful: war, the military-industrial complex that made the wars possible, racism, economic inequality, the global misery wrought by colonialism, the heavy hand of patriarchy, along with discrimination on various fronts. Since then I can add technological advents that have stirred the unhappy pot even more. Cloning, genetic modification, and artificial intelligence, with their potential for deep distress, were not on my list back then. Also, the drug plagues, almost too numerous to enumerate, had yet to appear. All of which is not to forget the melting glaciers.

Although I have done a fair amount of reading and thinking since then, what I meant and still mean in using that vague yet abiding term is a lifetime’s feeling about the afflicting soullessness of industrialism, an underlying quality that plays out in myriad ways, all stemming from what William Blake originally called the “dark Satanic Mills,” and that has left me with a persistent heartache: the works of man disparaging life itself. I wasn’t alone in feeling that way. Very different people—Bob Dylan, Paul Goodman, Joan Didion, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Anne Sexton, Norman Mailer, Rachel Carson, Kurt Vonnegut, James Baldwin, Joni Mitchell and what feels like a raft of others—felt similarly and had something to say about it. “Twenty years of schooling and they put you on the day shift,” as Dylan, who had an intuitive genius for getting at the heart of the matter, put it. The farm in “Maggie’s Farm,” another intuitive leap into the heart of the beast, was in essence a factory, which is what so much of so-called agriculture is. Dylan was wry but he knew of what he spoke.

The feeling speaks to a ruination based not just on the relentless, careless exploitation of the environment, though that is ghastly enough, but an inner ruination, too, a ruination that has issued in many forms—suicide, despair, crime, addiction and what has ubiquitously come to be called “trauma.” Many of us, understandably enough, try to minister to the behaviors that emanate from the essential situation, a situation that is world-wide and that dwarfs the various political and ideological dispensations which are joined at the hip with the factories and their seemingly endless manufactures. As the recipients, we know products on top of products, a veritable artificial cornucopia presided over foremost by plastic. It is hard not to feel that is precisely what people themselves are—the manipulated products of the innumerable concatenations of The System. Stalin, to choose one spokesman for one concatenation, spoke of writers and artists as “engineers of the human soul,” which is to say they were to follow in the footsteps of the industrialism that he embraced as part of the Soviet destiny. The very notion of the soul in that context seemed a grotesque irony and remains so, to say nothing of those “engineers” who died in the Gulag.

At this point, you may be wondering if I am going to pull the nostalgia card out of the deck and surmise that once upon a time the human condition was better. The short answer is that it wasn’t better but it was different. A world rooted in the earth is literally different from a world based on energy-consuming machines. That rooted world was typified by serfdom and slavery, whether in Ireland, Italy, Russia, the American South, China, or the colonized Caribbean. Land was held by the few, not by the many. Those who held the land had no inclination to give it up and were fine with blessing and rationalizing oppression as they saw fit. Those in the rooted world understood, however, that they lived on earth. How could they not? That earth—and here I very much mean the soil—was their grief and their solace as was whatever religion—Indigenous, Christian, or otherwise—that sustained them. For many, one simple fact loomed: starvation was never far away. Nor was brutality.

And what of a lifetime spent tending machines? For twenty-five years I worked in a mill town and came to have a strong sense of people laboring at various machines to make paper, to make shoes, to make wooden implements. After all, people in New England, especially women, had been doing this for a long time in places like Lowell, Lawrence, and Manchester. In that regard, I can say that none of the people whom I knew suffered from inflated, much less Utopian, notions of what they should be doing in this world. They were doing something; they were doing it with others; there was a knack to it; and it paid them a “living” (an equivocal phrase). Typically, they left it at that. Plenty else was available for them, be it hunting, playing cards, or churchgoing, or, as was often the case, all three. Their heartaches tended to manifest themselves in alcohol and abuse. They were not prone to point fingers, tending instead to suffer in silence excerpt for the occasional violence that was far from silent. Repression was manifested in a terse greeting, a shrug, a rueful smile verging on bitter.

Formerly, the mills routinely despoiled the rivers but had started to clean up their acts. In most cases, the rivers had served their industrial purposes. Technology and money had moved on. Now they were just rivers. What they meant to anyone around me was sketchy, just as what the earth meant was sketchy. So many human purposes intervened that it was easy to think that human purposes were all there was. The earth was where, as Joni Mitchell put it, they put up a parking lot. People were free, whatever that meant, and thus resided within an uncertainty that partook both of possibilities and grinding routines. I had the latitude to bemoan The System but did less and less bemoaning as the years went by. I loved the earth and had my own routines. Each day had a smidgen of unfettered gratitude that I kept to myself, or it came out in poems that, to the world-at-large, seemed like the same, kept-to-myself thing.

Yet all along I have known that I was witnessing something terrible, something I had been told about in the 1960s by the people I cited at the beginning of this essay, an imbalance that was coming all too true. As with Allen Ginsberg, some of them had been enlightened by William Blake, who was one of the first to sound the spiritual alarm and point to the pollution that inflicted not only industrial wounds to the earth but existential wounds that called for an atonement that was not forthcoming. The very notion of such atonement would never fit within the halls of parliaments, chemical weapons labs, and banking houses nor in churches, for that matter. Humankind never has been very aware of the consequences of their group actions, perhaps because large groups, in particular, are inherently thoughtless. Mass thinking, as Simone Weil pointed out, was no thinking. Or as W. H. Auden put it, neither love nor logic influenced such groups. To back off, to query, to think twice has been something like impossible without some violence, such as revolution, interceding, a violence that created another set of dilemmas to be pushed aside in the name of revolutionary certitude.

Meanwhile The System thrived in the sense that money begat more money and machines begat more machines. Who controlled The System, while interesting for both speculative and historical reasons, remained at once in plain view and hidden. You could see the men on the floor of the stock exchange busy with their clamor but behind those men stood other men and behind those men stood others in a seemingly endless trail. Clearly, the ways of power had their grooves. Apologies were not forthcoming since apology was weakness and, furthermore, what was there to apologize about? Hadn’t the “standard of living” kept rising like an inexorable ocean? Everything was okay. People had needs and wants. The products answered them. If people wanted to believe there were cabals, well, that word was in the dictionary. There were, for instance, so-called “intelligence agencies” cloaked in secrecy. And if someone wanted to believe that the way “civilized” people lived was a system of some sort, which was to say a palatable imprisonment, that was permissible in non-totalitarian states that were, nonetheless, tied increasingly to security and surveillance as ways of life—unfree freedom.

For all the talk of good vibrations, the era in which I came of age was not marked by optimism. None of the writers and poets I cited earlier would be distinguished by that quality. War, dirty tricks, lies, and assassinations took large tolls. The era was marked, however, by an uncontrolled vitality, a vitality that frightened the forces of repression precisely because it seemed uncontrollable. Where would it lead and how would it end? “Exuberance is beauty,” Blake wrote. Exuberance has no system. It takes no pleasure in accumulation. It revels in being. Children at play know this, as do adults when they dance and sing, pitch horseshoes and swing a badminton racquet. The System replies that we all must grow up and that, to cite one notorious motto, work makes us free. We put away our childishness. We do but for some, such as myself, the feeling bred by the industrial world remains. We are the children of nature, not the children of machines. We don’t seem to be able to get that straight.

Copyright 2024 Baron Wormser

Baron Wormser’s many books include The History Hotel (CavanKerry, 2023). He founded the Frost Place Conference on Poetry and Teaching and also the Frost Place Seminar.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

3 comments on “Baron Wormser: The System”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on April 21, 2024 by Vox Populi in Environmentalism, Health and Nutrition, Opinion Leaders, Personal Essays, Social Justice and tagged Allen Ginsberg, Baron Wormser, Bob Dylan, capitalism, feudal, mill town, post-industrial, river, Simone Weil, The System, W.H. Auden, William Blake, working class.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-mMWSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,808,134

Rose Mary Boehm responds from Peru: ‘Baron Wormser: this is another brilliant essay expressing with the right words and great intelligence what I would like to be able to express that well. “And if someone wanted to believe that the way “civilized” people lived was a system of some sort, which was to say a palatable imprisonment, that was permissible in non-totalitarian states that were, nonetheless, tied increasingly to security and surveillance as ways of life—unfree freedom.” Indeed.’

LikeLiked by 3 people

How profoundly intelligent and convincing, this essay! What a brilliant mind you have, dear Baron, dear old friend!

(And how the admittedly pusillanimous 80 year old grandma in me needs– so much — to make believe I never read it, and continue weeding the 0.14 acre of my garden — repeating, over & over, Voltaire’s: “Life is bristling with thorns, and I know no other remedy than to cultivate our own garden.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Laure-Anne!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person