Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Mike Vargo: Is There a Real Me?

In basic French, noir means black. In culture, a noir film or book is dark, cynical, and makes you wonder about the meaning or value of anything. One of the noirest passages in noir fiction comes in Raymond Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye.

As the narrative unfolds, private detective Marlowe gets tangled in a long string of crazy cases and perilous predicaments, which stem from his odd friendship with a very odd man named Lennox. Lennox himself is no longer around. He had fled the scene to protect his own hide, but trouble caught him anyway and he died, it seems, down in Mexico. One morning a visitor appears at Marlowe’s office. A Mexican gentleman, dressed like a duke and exuding elegance, claims to have information about the demise of Señor Lennox.

The man’s tale is dubious, inconclusive. Then Marlowe leaps to the conclusion that’s been hiding in plain sight. The visitor is Lennox — disguised in a fancy suit and dark glasses, altered by plastic surgery, and splendidly faking a Hispanic-inflected English. Lennox had thought Marlowe would be delighted to find his old pal alive. Wrong. Marlowe doesn’t care to renew their bond. Not because he’s angry, the detective explains, but because the Lennox he thought he knew doesn’t seem to exist. “You’re not here,” Marlowe says. “You’re long gone.” And when Lennox protests that the masquerade is just an act, Marlowe fires back “You get a kick out of it, don’t you?”

Now Lennox regains his cool. He replies with the lines that chill me to my empty bones:

“Of course. An act is all there is. There isn’t anything else. In here,” says Lennox, tapping his chest, “there isn’t anything.”

**

Maybe Lennox wasn’t always an empty man. In the Second World War, he had signed up for treacherous combat missions, and saw all the horrors that the job entails. He can (and does) argue that his time with a commando unit was what hollowed him out. Yet I can’t help feeling that Lennox also speaks for me. And maybe for everyone. An act is all there is. There isn’t anything else.

I never went to war. In my young-adult years, I was part of a circle of friends who engaged in inquiries into the meaning of life and experiments in the best way to live. Our senior member was an old guy of 40 who, after high school, had given up his dream of being a jazz sax player, but then repeatedly failed to make a go of it as a practical working-class citizen. Now he was out to rediscover his true identity, busking in the streets while he shared rented rooms with college-educated deepthinkers. A young computer whiz aimed to be equally fluent in the arts of digital expression and human expression; one of his projects was reading Finnegan’s Wake, a page per day. Several women were carving out independent, entrepreneurial careers in various fields; none aspired to a job on a corporate hamster wheel.

A common thread among us was the desire to live “authentically” — not as an act, but rather, putting aside the pretenses that are customary in our society. Shunning the masks that are meant to hide the real self. Never faking anything.

Throughout my day-to-day activities I carried the conviction that nothing could be done right, nothing from shopping to sex, unless I did it from the space of authenticity. So I spent a lot of time trying to be authentic. This, despite the obvious irony. If you have to try to be authentic, it’s not authentic, is it?

**

These days I have a great act, a routine I’ve performed countless times: Mike the nice guy, of whom people think highly. In this role I am cheerful and helpful, and a so-called good listener — eager to hear what others are up to. You probably know someone like that. Someone you can tell your stories to. A person who asks questions to draw you out, almost like an interviewer, and who will stay with you to the point where you think Whoa, I’ve been rambling on about myself. Better ask what’s new on their end.

Yep. That’s me doing the act. I even chose a profession that requires me to do it, journalism. Which I practiced full-time for years and lately part-time while freelancing. “Good morning, sir or ma’am! I’m writing about such-and-such and I’d like to hear your take on it … May I visit to see how you work? …”

In both reporting and just plain interactions with people, I can run this routine to perfection, and let’s be clear about one thing: it’s not all a put-on. Not phony baloney all the way down. At depths that may vary from case to case, I feel “sincerely” interested in the lives of others. And “genuinely” curious about the realms they explore and experience. Journalism is fun because it gives you license to step right in. As a general-interest feature writer I’ve interviewed and been up close with people from scientists and artists to CEOs and criminals (who aren’t necessarily the same person), and more. Then I am authorized, literally, to describe their worlds to the public: Here is why some researchers in climate science are studying the properties of clouds. This is what it’s like to belong to an outlaw motorcycle club.

A fine occupation. When I’m immersed in the work — soaking up what other people do, channeling their thoughts and actions through the medium of writing — it’s as if I get to live lives other than my own. Temporarily, by proxy, as it were. And there’s the rub.

I, myself, become a chameleon. Or to state it more harshly, a professional dilettante. I get to put on these many faces, wear these skins, for just a little while each. Without having to commit to a lifetime of grinding through piles of scientific research data. Or to living at the risky fringes of the mainstream. And the same holds true for relations with friends. If I devote enough time to listening to your identity crisis and trying to help you with it, I don’t have to confront mine.

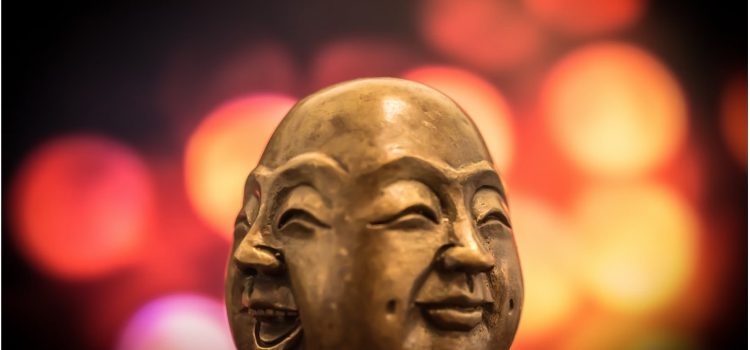

This act that I’ve developed is like a Russian nesting doll. An act with layers of sub-acts stacked inside. Which leads back to the existential question. Is there a real me somewhere in there, at the core?

**

Sometimes I think not. Sometimes I feel like a ghost of a ghost.

There appears to be no question about my physical identity. Sitting here at a desk, I can actually see most of my body if I roll back the chair and look down. The feet, the hands, definitely exist and they are definitely mine. I feel the little churns and tics in my innards that say the vital organs are working. But as for the essential who or what that is sustained by this mechanism, and is also in charge of operating the mechanism: that identity feels uncertain. Shockingly elusive. Despite having a history and responsibilities that should serve to lock it in place, it’s a rogue consciousness. It mentally manufactures (“imagines”) out-of-body experiences — as if wanting to go somewhere else, where it can be something else.

This rogue consciousness even sends the body in random directions. It makes me a peripatetic thinker, walking while I think or thinking thoughts triggered by the walk. Sometimes in the course of composing a paragraph or planning what to say to someone, I find myself blocks away from home. Staring, perhaps, at the local playground where children romp and squeal on the slides while moms and dads chat in a cluster nearby. Much can be triggered by such a scene.

But it doesn’t take me back to the playgrounds of my past. Instead I remember past walks. Walking through another neighborhood now gone, on early-evening strolls with my father. As the daylight dims, the lights inside houses light up and my dad says Hey, we haven’t been on this street. Let’s walk up there. Hm, look at that house …

I still take these intentional walks as a grownup, except solo. In a residential urban area anywhere I feel compelled to walk and stare at houses. Heidegger said “Language is the house of being,” but in plainer terms, a house is a house of being. So I walk and wonder what I would be if I lived in that big old Victorian, or up in the top-floor apartment of the building on the corner: a perch fit for a hawk.

My actual house is nice, a vintage Arts and Crafts with nifty interior woodwork, and though my actual life here may look like easy street, it leaves me uneasy. Maybe it’s just a long-running act that plays over and over like a video on a loop. One act out of many possibles.

**

Believing in a real self would be easier if the self were not so inconsistent. The nice-guy, good-listener me manifests itself often but not always. Other versions clamor to be in charge, and sometimes they are. A particularly troubling version is greedy and heedless: bent on having whatever it wants (and its wants can be many and strange), heedless of consequences.

Without getting clinical — I am neither a clinician nor a person diagnosed with a mental disorder — I would venture to say this. Alternate versions of the self are a different kind of psychic animal than what we call moods. Moods can change frequently. Perhaps you feel up and optimistic early in the day, then deflated later. Or amused and giggly for a bit, then passionate and purposeful, fueled by a spurt of anger. Mood shifts are changes in the emotional weather. Except in severe cases, they seldom cause problems. Altogether I welcome them as elements of the richness of being alive. They do not alter who I seem to be. My “values,” or whatever you want to call the forces that shape and drive a person, usually stay the same; they’re just singing across a range of notes on the scale.

An alternate self is another tune entirely. It takes over. Picture a scene in a fantasy movie, where a transformer spell turns a character’s hands to talons, and the head to that of a long-beaked birdbrain. That’s greedy and heedless. It might be activated by desire for a speciic something, or by vague discontent with the status quo. And once this other self blooms into shape it can keep operating for days and weeks. Maybe it acts out flagrantly, brandishing its freaky form as it scatters furniture out of the way in pursuit of what it wants. But it is more likely to operate in stealth mode.

The birdbrain is smart enough to know that showing itself will probably spoil the game. So it lurks under the radar and works up a cover story. And a perfect candidate to serve as secret agent lives close by: the nice guy. The nice guy is already on a stealth mission anyway, people-pleasing to win praise and esteem, which makes it easy to convert him to a double agent: a people-pleaser with a sting. Pleasing people in sly ways that induce them to produce the goods desired by the ravenous, birdbrain self.

This is not a hypothetical example. It happens in my life, and so do many inner transactions of a similar kind. Some are nefarious and some are well-intentioned — acts of strategic benevolence, you might say. Performances that are scripted to tackle a tricky interpersonal problem or help someone feel better. But either way it’s a dizzy, busy scene inside the creature known as me.

Once, when I worked as a staff writer at a magazine, the editor in chief strolled into my office while I was finishing a crucial story. The chief was a good fellow, more a friendly colleague than a boss, and when he asked how the piece was going I said “Take a look.” He sat next to me. Saw what I had on the screen. Didn’t like it. He thought the story veered off course, missing the main point. I thought it drove beyond the obvious exit to the message behind the message. We debated the issue. Collegially, at first. Then somehow the conversation splintered apart. Next thing I know, we’re both out of our seats, shouldering and hip-checking one another sideways and clawing at the keyboard. Two heads, four hands, and forty fingers battling to make the story turn this way or that.

Years have passed. The man and I can laugh about the incident, but it’s not funny that the scene is reenacted again and again, internally. Every time two or more selfs battle over how my life’s story should go.

The question of whether I have a real self (or at least a primary self) is more than an academic question. It can’t be dismissed as an interesting but irrelevant exercise in navel-gazing. The answer, if there is one, speaks to who I am and what my capabilities are. It’s a question of how well I can control my path or create new paths. “I am the master of my fate / I am the captain of my soul”: yeah, maybe. But maybe the captain’s chair is up for grabs and the ship will sail off to wherever it is steered by whoever.

**

What do experts say about the situation? Searching the web, I came across a scholarly essay by Daniel Dennett. He is a philosopher and cognitive scientist, a black-belt mindbender. His essay had a title I couldn’t ignore: “The Self as a Center of Narrative Gravity.”

Dennett argues that what we call the self is just a “theorist’s fiction.” When we think or speak of a person as having a single, coherent self, he says, we’re invoking a theoretical concept — a concept that may be useful in certain ways, but doesn’t really exist. He compares it to a concept from Physics 101: the center of gravity of an object. Although it’s very useful to treat objects as having a center of gravity, we can’t point to an atom within a given thing that “is” that center, Dennett contends. And what if we have a complex object, with moving parts that tip the collective balance? What if the object contains loose stuff that shifts around? The center of gravity changes.

A human mind, Dennett continues, is vastly more complex than the typical inanimate object. Citing research in neuroscience, he writes that “the normal mind is not beautifully unified, but rather a problematically yoked-together bundle of partly autonomous systems.” Furthermore, “All parts of the mind are not equally accessible to each other at all times. These modules or systems sometimes have internal communication problems …”

Dennett’s conclusion: It seems “we are all virtuoso novelists, who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behavior, more or less unified, but sometimes disunified, and we always put the best ‘faces’ on it we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story. And that story is our autobiography.”

Then the kicker: “The chief fictional character at the center of that autobiography is one’s self. And if you still want to know what the self really is, you’re making a category mistake.”

**

The plot grows thicker if you read Sherry Turkle. This eminent sociologist first won public notice with her 1984 book The Second Self, which does not refer to a mysterious doppelgänger. Unless you consider a computer to be a mysterious doppelgänger. Turkle’s early book documented and put forth a theory that’s now widely accepted: using computers can change how we think, including how we think of ourselves. It can change the concept of one’s self. Turkle had met a computer-science student at MIT who believed that human minds work by the same processes as computers. (False, or at best a misleading analogy.) She’d seen small children playing with personal computers and debating whether the machines were alive. Weird conflations everywhere.

Turkle, the head of MIT’s Initiative on Technology and Self, has found plenty to write about since The Second Self. In 1984, the public web hadn’t yet come along, or social media with its influencers and misinformers. Or smartphones, or generative AI. Turkle’s maxim: “Information technology is identity technology.” The tech we use gives us the opportunity (the illusion?) of having multiple selfs outside as well as in.

Postscript: The Ancestors

Did you ever think that reading might be bad for you? I have suspected it. Suspected that philosophy and literature and serious nonfiction can be more insidious than trivialities and idiocies on the web, due to their power to lead a person into overthinking aspects of existence that might go better if they aren’t thought about at all.

Yet I keep on reading. Damn the risks and full speed; I want answers. In Norbert Wiener’s The Human Use of Human Beings — a book-length rumination by a founder of the field of cybernetics — a paragraph says, in part,

“Our tissues change as we live: the food we eat and the air we breathe becomes flesh of our flesh and bone of our bone, and the momentary elements of our flesh and bone pass out of our body every day with our excreta. We are but whirlpools in a river of ever-flowing water. We are not stuff that abides, but patterns that perpetuate themselves.”

True physically, and probably true of our thoughts and behaviors — a swirl of patterns perpetuating themselves. And where do the patterns come from? Some we are born with, no doubt. For example, the startle response. When you hear a sudden loud noise you jump, or at least twitch. So do cats. Then there are higher-order patterns, which can be particular to the individual: a friend’s unusual patterns of speech. How one person reasons things out versus the way another does. Or the long-running collective cycles, such as the rise and fall of empires. Which I mimic in microcosm when I alternate through cycles of sophisticated success and brute stupidity. Where do these patterns come from?

The answers we hear are half-and-half answers: Each of us is shaped partly by nature and by nurture. We have free will but it’s limited free will, within a range of options and decisions that are determined. These explanations make sense but don’t quite tell me what I’m looking for. Could it be floating in front of my face?

I love to swim in rivers and lakes and oceans. Natural bodies of water call to me. So I wade in and swim, and haven’t come close to drowning, except for once. It happened in the dining room of an apartment.

Talking with friends over dinner, I reached for a glass of water and drained a huge gulp. All of it went down the proverbial wrong hole. I felt a titanic, crushing jolt in my chest and must’ve panicked. Definitely I blacked out, unaware of thrashing around the room and crashing to the floor. When consciousness returned, I saw worried faces crouched close and my chair upside-down, legs angled up. Small items lay where they’d been flung. This odd panorama, however, felt mundane compared to the vision that I had been granted while I was carried away.

Out of a dark, deep background, a cavalcade of ancient creatures emerged. One could say they “materialized” but I would say they spiritualized, in visible forms. Dinosaurs loomed and swirled: sinuous two-legged predators with mouths open and placid dinosaurs, stolid on four legs. Plesiosaurs and beasts of the sea. In turn they swam before me and passed by as others appeared: unnameable beings with hair and humps, and heads that mutated. None looked at me, but I sensed they knew I was there. I watched in delirious awe. Having read a bit of Jung, I remember thinking, in a silent voice that spoke: Oh, the archetypes! And then, as if translated: The ancestors!

Next the vision vanished and I was back in the company of barefaced, babbling humans. Where I have remained ever since. Babbling on through the manufactured jungles of the Babylons created by our incredibly facile modern breed.

The ancestors: do we have dinosaurs in our DNA? That is unknowable, I’ve read, although scientists say we share about 65% of our genetic code with birds, who are thought to be descended directly from dinosaurs. But I don’t think the whole story can be learned simply by reading what’s in the current genome.

If evolution is a process of adaptation — if the survivors, at any stage, are the beings that fare best in a changing environment, and thus are able to pass along their genes — then ultimately there is no clear line between nature and nurture. It seems to me that the two dance together. And I am the product of a very long dance, performed by innumerable dancers.

Modern humans arrived after billions of years of evolution, reaping the accumulated benefits. Some humans couldn’t handle the load and the benefits went bitter. In the Bible chapter Mark 5, written about 2,000 years ago, Jesus meets a howling madman. When he offers to heal the madness by casting out the evil spirit, there turns out to be more than one inside the man. “What is your name?” Jesus asks, and the demon(s) say(s) “My name is Legion, for we are many.”

About 1,800 years later, Walt Whitman took a more upbeat view of his inner multiplicity:

“Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

And a couple of hundred years after Whitman, the hordes showed up in me. These hordes include the sea sponges and plesiosaurs whose spirits yearn for the natural waters. They include the Golden Horde of the Mongol empire, my now-deceased mother, The Three Faces of Eve, and the contemporary author Ruth Ozeki, who wrote the hall-of-mirrors novel A Tale for the Time Being — from which I absorbed a few strands of her being.

So maybe the bottom line is this. Perhaps I shouldn’t worry about seeming to have a mere handful of selfs, performing acts that aren’t really me, because the repertoire is in fact immensely larger than any part of me can comprehend. And the feeling of emptiness at the core? Maybe it’s a craving for what can’t be had. A craving to be unique among all creation while also having the ability to be anyone, anywhere.

That’s my best shot at putting it into words and I’ve written enough already. One night, on a visit to a city far from here, I attended a poetry reading. The featured artist stepped up to the stage and arranged her papers on the podium. She then prefaced her poems, her act, with a disclaimer. “All of this is in code,” she said. “The real words take longer.”

Copyright 2024 Mike Vargo.

Image: Bronze Buddha Head 4 faces – Vintage Japanese – Etsy.

Mike Vargo is a freelance writer based in Pittsburgh. The essay is a draft of a chapter for a book-in-progress.

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I read this with much interest–you have a probing and apparently a well educated mind. I would only caution that beyond the myriad complexity you allude to, from that of the galaxies in this vast universe to the ‘universe’ we call the mind, there may be something astoundingly simple–so simple, so beautiful, so ineffable we cannot comprehend it in this world, though many may sense it and some even experience it. I, for some reason, was one of the latter, as I wrote of on Vox Populi on January 4, 2023 under the title ‘The Day I Remembered My Soul’. It was also the day that shattered my former faith in secular materialism, the belief that only matter has reality.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Nolo!

>

LikeLike

Through a glass darkly, indeed. I’ve just read your piece, Nolo, and it will stay with me.

LikeLike

What a wonderful, excellent, thought-provoking essay. Please write that book. Many time I tip-toed into this quicksand of overthinking and pulled out too quickly, fearful of being swallowed whole. “For we are legion”

LikeLike

All of us here thank you, Rosemary!

LikeLike