Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

Baron Wormser: Disunited Delusions

As a writer and poet, one unlikelihood about which I have fantasized is the nation’s lawmakers, Congressmen and Congresswomen, taking a week out to gather for the purposes of reading some works of American literature, listening to some lectures, and talking among themselves about books that are a crucial part of what has been created in the United States. One course of study that I would propose would be “The Delusional United States” and feature novels that probe the effects of living in a delusional society, a vein American fiction is rich in. I would offer such works as Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Robert Stone’s A Hall of Mirrors, and Philip Roth’s American Pastoral as classic texts. Some of the Senators and Representatives may have read them in high school or college but they could read them again. Some (most?) may never have heard of them.

Even as fantasies go, mine is preposterous. I can well hear the objections: “We are busy. We are important people. We have no interest in books that purvey a gloomy view of American life. We do not feel that works of fiction have any bearing on real life. We resent being told what to read.” Even as I write this, I can hear strident voices inveighing about the absurdity of my proposal and going to the usual lengths to demonstrate infallible commonsense. Muttering Bob Dylan’s “Nothing was delivered,” I would be left to skulk off into my corner, assuming I had a corner.

The ur-text of my course would be The Confidence Man. Melville showed in that novel, as well as any American writer has ever shown, how the scam is at the heart of the American endeavor, how one scammer goes after another scammer, and how no up or down really exists in American life: everything is open to manipulation, be it by means of flattery, lying, bragging, insinuation, false sympathy, bribery, or sheer cunning. The people of the nation exist as so much malleable material to be cozened as the confidence man sees fit. Since the American people have no long-standing connection to the earth (the novel takes place on a boat on April Fool’s Day), anything goes. Melville includes among his characters, one given to “Indian-hating” (as Melville terms it), an appellation that shows the author’s awareness of who the first Americans actually were and what happened to them.

What haunts the reader of Melville’s novel is how nothing, beyond petty grifting, is really occurring. We find ourselves in the emotional subsoil of American life, a constant, anxious tugging at the sleeves of credulity: “Do you believe me? Do you have confidence in me? Why don’t you have confidence in me? You should have confidence in me. Your failure to have confidence in me shows a failure within you.” The only true subject is money and how it changes hands. If money can be made, then any claim on behalf of money is justified. Ideals are for books, Sunday sermons, and editorial writers. The riverboat appears as a species of Dante’s Inferno, a place where everyone is sentenced to making the worst of the worst circumstances. All that matters is the wanton yet calculated energy of the scam, the inciting of cupidity, of insider knowledge, of bogus philanthropy, of making one more dubious common cause. Who, given the all-encompassing wiles of the book’s characters, would guess that in 1857 a very bloody civil war was right around the corner? For my part, I imagine Melville realized that the seemingly endless hustle had its limits.

That war showed that some ideals, however perplexed, adhered to the doings of the nation’s citizens, enough, in any case, for men to die for. No one, however, dies on Melville’s boat (unlike another boat Melville wrote about) and that speaks to what a weird, talky bubble the United States has been, the land of assertions that try, somehow, to fill in the void at the center of the American endeavor, that try to further a wanting that is always proclaiming its exceptional worth yet does nothing so much as weigh down its citizens or provoke them to castigate whatever bogeyman—liberals, Reds, immigrants, atheists, feminists, abortionists—threatens them. The United States is known for its open spaces, but mentally it has been a very cramped, Puritanical place where there never has been enough room. The Native people who were the recipients of numerous swindling treaties learned that lesson too well.

Politics as it has evolved in the United States represents a sort of merry-go-round that beyond responding to an economic crisis such as the Depression and the agitations of the Civil Rights Movement has gone nowhere. A voter can choose the finger-pointing of the right or the often self-righteous pieties of the so-called left, but both sides are steeped in that anxious American sense of something happening today or tomorrow that will justify the nation’s being, its less-than-manifest destiny. This could involve sending men to the moon or invading another nation in the name of democracy or proclaiming leadership of something called “the free world” or striving for an absolute state of social justice and correct behavior or making sure that history books have nothing disturbing in them. Whatever it is, it shows vigilant virtue on the march. It equates calm and reason with torpor and self-denial. Religious or secular, it has an excited, millenarian gleam in its eye. Some narrow paradise is over the next hill.

Surrounded by products, Americans tend to see themselves in that material light. The enormous emphasis on identity of one sort or another is understandable. Merely being human and enjoying what life has to offer during our brief time here is no help to the inventive, commercial juggernaut that runs the show and relegates the substantial debate that might characterize electoral politics to a sort of dumb show. No one on the main, televised stage is challenging the military-industrial complex or the national security state or the right to make vast profits. Americans can, however, claw one another to death over their rights.

To turn to 2024, Donald Trump, as an unrestrained American ego, seems like an allegorical figure of the sort that Melville had a fondness for—the Confidence Man, par excellence. As on the Mississippi steamboat, no one can get to the bottom of the alluring delusions he proffers. Who knows what “great” means or “again?” Who cares? The assertion is all and vindicates whatever lacks and grievances many Americans feel. Indifferent as Trump is to spirit, art, truth, and the earth, he speaks for an egotism that can applaud itself endlessly and that invites other egos to partake of the unholy spectacle. He represents the revenge of the individual that has no use for lawful, societal bonds, thus speaking to the “rugged” individualism countless politicians have praised. More than once, a mass of such “rugged” individuals has constituted a lynch mob.

A fair question to ask is: What is the point of all this bad feeling? Is this the result of expectations that can’t possibly be met? Or simply a sense of being lost amid all this material clamor and needing to blame someone for that hollowness that plays itself out in overdoses, addictions, and suicides? What saddens anyone who thinks for a minute is the colossal amount of negativity that has been unleashed. The importance of the United States rests in the example of people from varied backgrounds getting along. It’s a challenging feat that needs all the encouragement it can get. Many Americans—teachers, for one—try to do it every day. Instead, what politics treats us to is duplicity that insists on its sincerity, expediency that masquerades as principle, power-mongering that pretends to be scrupulous. It is a small step from the hustles on the steamboat to the national barker proclaiming, “Step right up. Get your MAGA hat. Costs only your life’s blood.”

A certain amount of miserable honesty resides in Trump’s scatter-shot denunciations. He is vexed because he sees himself as the ultimate American. It’s a raw place to live since his wanting can never be fulfilled. In his yappy, mean-spirited, hectoring way Trump is a sort of Sisyphus pushing the rock of disgruntlement up the hill. Other sorts of energy—caring, creating, cultivating, conserving—all get pushed aside. Happily and unhappily, the reality of the ever-growing environmental difficulties is going to render these antics even more pitiful. How much time we have to indulge them is very much another story. Melville knew something about ships of fools.

Copyright 2024 Baron Wormser

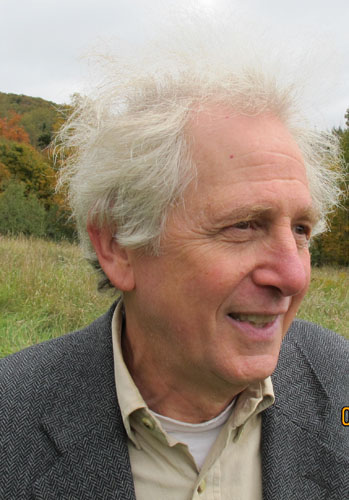

In 2000 Baron Wormser was appointed Poet Laureate of Maine by Governor Angus King. He served in that capacity for six years and visited many libraries and schools throughout Maine. His books include The History Hotel (CavanKerry, 2023).

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

share this:

Related

3 comments on “Baron Wormser: Disunited Delusions”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Information

This entry was posted on February 11, 2024 by Vox Populi in Literary Criticism and Reviews, Opinion Leaders, Personal Essays, Social Justice, War and Peace and tagged 2024 presidential campaign, Baron Wormser, Disunited Delusions, Donald Trump, Herman Melville, The Confidence Man.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p4xqzG-mjfSearch

Search

Blog Stats

- 5,963,416

So well written. The essayist I aspire to be.

LikeLike

and Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike