Vox Populi

A curated webspace for Poetry, Politics, and Nature with over 6,000,000 visitors since 2014 and over 9,000 archived posts.

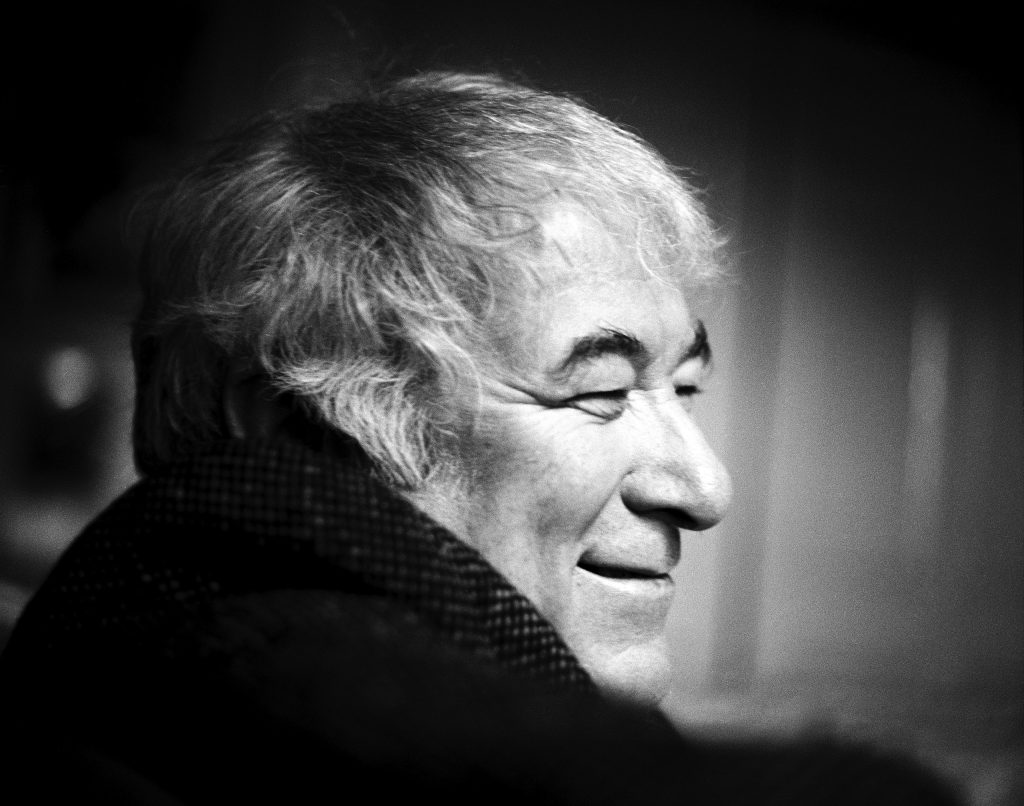

Seamus Heaney: Pangur Bán

A translation of the anonymous ninth-century

Irish poem about a monk and his cat

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

More than loud acclaim, I love

Books, silence, thought, my alcove.

Happy for me, Pangur Bán

Child-plays round some mouse’s den.

Truth to tell, just being here,

Housed alone, housed together,

Adds up to its own reward:

Concentration, stealthy art.

Next thing an unwary mouse

Bares his flank: Pangur pounces.

Next thing lines that held and held

Meaning back begin to yield.

All the while, his round bright eye

Fixes on the wall, while I

Focus my less piercing gaze

On the challenge of the page.

With his unsheathed, perfect nails

Pangur springs, exults and kills.

When the longed-for, difficult

Answers come, I too exult.

So it goes. To each his own.

No vying. No vexation.

Taking pleasure, taking pains,

Kindred spirits, veterans.

Day and night, soft purr, soft pad,

Pangur Bán has learned his trade.

Day and night, my own hard work

Solves the cruxes, makes a mark.

Translator’s notes:

This poem, found in a ninth-century manuscript belonging to the monastery of St. Paul in Carinthia (southern Austria), was written in Irish and has often been translated. For many years I have known by heart Robin Flower’s version, which keeps the rhymed and endstopped movement of the seven-syllable lines, but changes the packed, donnis/monkish style of the original into something more like a children’s poem, employing an idiom at once wily and wilfully faux-naif: “I and Pangur Bán, my cat,/’Tis a like task we are at…,” “’Tis a merry thing to see/At our tasks how glad are we/When we sit at home and find/Entertainment for our mind,” and so on.

Sometimes known as “Pangur Bán” (“white pangur”—“pangur” being an old spelling of the Welsh word for “fuller,” the man who works with white fuller’s earth), sometimes known as “The Scholar/Monk and his Cat,” the poem pads naturally out of Irish into the big-cat English of “The Tyger.” And since Blake’s meter acted as Flower’s tuning fork, and as Yeats’s when Yeats came to write his exhortations to Irish poets, I was glad to “keep the accent” and thereby instate the author of “Pangur Bán” at the head of the line of those Irish poets who are meant to have “learned their trade.”

Like many other early Irish lyrics—“The Blackbird of Belfast Lough,” “The Scribe in the Woods,” and various “season songs” by the hermit poets—“Pangur Bán” is a poem that Irish writers like to try their hand at, not in order to outdo the previous versions, but simply to get a more exact and intimate grip on the canonical goods. Nevertheless, had it not been for the editor’s invitation to contribute to this issue, it’s unlikely that I would ever have made bold to face the job: the tune of the Flower version is ineradicably lodged in my ear, and I just assumed that for me “Pangur Bán” would always be a no-go area.

A hangover helped. Not so much “tamed by Miltown” as dulled by Jameson, I applied myself to the glossary and parallel text in the most recent edition of Gerard Murphy’s Early Irish Lyrics (Four Courts Press, 1998) and was happy to find that I had enough Irish and enough insulation (thanks to Murphy’s prose and whiskey’s punch) to get started.

Originally Published in Poetry: March 28th, 2006

Seamus Heaney is widely recognized as one of the major poets of the 20th century. A native of Northern Ireland, Heaney was raised in County Derry, and later lived for many years in Dublin. He was the author of over 20 volumes of poetry and criticism, and edited several widely…

Discover more from Vox Populi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.